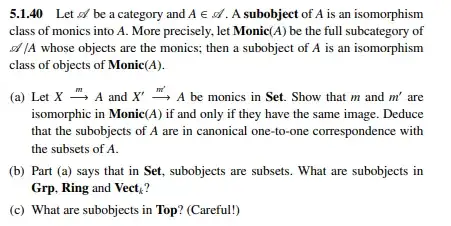

I'm working on this exercise:

(a) Here's how I understand (a) - is that right?

Suppose $im(m)\ne im(m')$. WLOG suppose there is $y\in im(m')$ but $y\notin im(m)$. Say $m'(x)=y$. If $\alpha:X'\to X$ is any map that makes the triangle commute, then we must have $m(\alpha(x))=y$, which contradicts the fact that $y\notin im(m)$. So there are no morphisms $(X,m')\to (X,m)$ at all, let alone bijective ones. This part doesn't seem to use the fact that $m,m'$ are monic.

Conversely, suppose $im(m)=im(m')$. Since $m,m'$ are monic, they are injective, so for every $y\in im(m)$ there is a unique $x\in X$ and $x'\in X'$ that are mapped to $y$. This enables one to establish a bijection between $X$ and $X'$ in a way that the triangle commutes.

So $m$ is isomorphic to $m'$ iff $im(m)=im(m')$.

The "canonical one-to-one correspondence" is, I believe the following. Given an equivalence class of an arrow $m: X\to A$, map it to $im(m)$. This is well-defined by the above result. This map is surjective: the preimage of $S\subset A$ is the map $S\to A$ given by $x\mapsto x$. Injectivity is clear too: if two equivalence classes are mapped to the same set, then consider one representative from each class; their images are the same, so they lie in the same class.

(b) Common sense suggests that the answer should be "subgroups, subrings, vector subspaces". In all these categories, monics are the same as injective homomorphisms. This being so, doesn't the same argument as above apply (according to which subobjects are again subsets)? Where should the requirement on closure under operations should come from?

(c) As far as I understand, the discussion here implies that in $\mathbf {Top}$ monics are the same as injective continuous maps. So the same question arises as in (b).