In order to understand the topic of "presentation of a group", I would like to work out the following example: $\def\Z{\mathbb{Z}} \def\iso{\cong} \def\llg{\langle} \def\rrg{\rangle}$

$\Z\times \Z \iso \langle a,b\,|\, [a,b]=1\rangle$, where $[a,b]:=a^{-1}b^{-1}ab$.

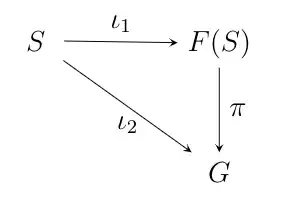

This example appears in Section 6.3 of Dummit and Foote's Abstract Algebra. The definition of generators and relations there is somehow confusing. It begins with a given group $G$ and a subset $S$ of $G$ such that $G=\llg S\rrg$ and then assume a subset $R$ of the free group $F(S)$ has the property that its normal closure in $F(S)$ equals to the kernel of the group homomorphism $\pi$, where $\pi$ is defined by the following commutative diagram:

where $\iota_k$, $k=1,2$, are the inclusion maps. This a priori appearance of the group $G$ in the definition makes statements like the example above difficult to understand. To approach the example above, I will use the following definition instead:

Let $S$ be a set and $F(S)$ the free group on $S$. Let $R$ be a set of words in $F(S)$, i.e. $R\subset F(S)$, and $N$ the normal closure of $R$ in $F(S)$. The group $\llg S|R\rrg$ is defined as $$ \llg S|R\rrg=F(S)/N $$

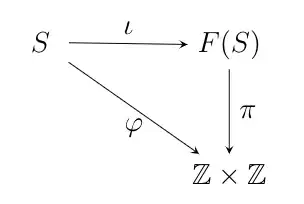

Now let $S=\{a,b\}$, $\varphi(a)=(1,0)$, $\varphi(b)=(0,1)$. By the universal property of $F(S)$, there exists a unique group homomorphism $\pi: F(S)\to \Z\times\Z$ such that the following diagram commutes:

i.e., $\pi\circ\iota=\varphi$. If I can establish the following,

- $N=\ker\pi$;

- $\pi$ is surjective, (trivial because $\pi(a^mb^n)=m\pi(a)\oplus n\pi(b)$)

then by the first group isomorphism theorem, the proof is done.

The inclusion $\ker\pi\supset N$ is easy; since $\ker\pi$ is a normal subgroup, it suffices to show that $\ker\pi\supset R$: $$ \pi([a,b])=[\pi(a),\pi(b)]=[(1,0),(0,1)]=(0,0)\;. $$

How can I show the other direction $\ker\pi\subset N$? Or is there anything else I can do to get around this step?