inspired (again) by an inequality of Vasile Cirtoaje I propose my own conjecture :

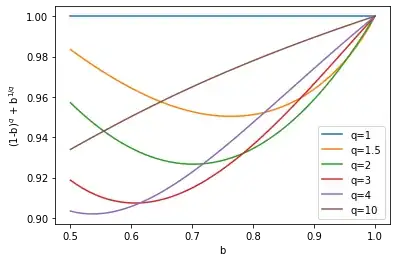

Let $x,y>0$ such that $x+y=1$ and $n\geq 1$ a natural number then we have : $$x^{\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)^n}+y^{\left(\frac{x}{y}\right)^n}\leq 1$$

First I find it very nice because all the coefficient are $1$ .

I have tested with Geogebra until $n=50$ without any counter-examples.

Furthermore we have an equality case as $x=y=0.5$ or $x=1$ and $y=0$ and vice versa .

To solve it I have tried all the ideas here

My main idea was to make a link with this inequality (my inspiration) see here

So if you can help me to solve it or give me an approach...

...Thanks for all your contributions !

Little update

I think there is also an invariance as in question here Conjecture $a^{(\frac{a}{b})^p}+b^{(\frac{b}{a})^p}+c\geq 1$

Theoretical method

Well,Well this method is very simple but the result is a little bit crazy (for me (and you ?))

Well ,I know that if we put $n=2$ we can find (using parabola) an upper bound like

$$x^{\left(\frac{1-x}{x}\right)^2}\leq ax^2+bx+c=p(x)$$ And $$(1-x)^{\left(\frac{x}{1-x}\right)^2}\leq ux^2+vx+w=q(x)$$

on $[\alpha,\frac{1}{2}]$ with $\alpha>0$ and such that $p(x)+q(x)<1$

In the neightborhood of $0$ we can use a cubic .

Well,now we have (summing) :

$$x^{\left(\frac{1-x}{x}\right)^2}+(1-x)^{\left(\frac{x}{1-x}\right)^2}\leq p(x)+q(x)$$

We add a variable $\varepsilon$ such that $(p(x)+\varepsilon)+q(x)=1$

Now we want an inequality of the kind ($k\geq 2$):

$$x^{\left(\frac{1-x}{x}\right)^{2k}}+(1-x)^{\left(\frac{x}{1-x}\right)^{2k}}\leq (p(x)+\varepsilon)^{\left(\frac{1-x}{x}\right)^{2k-2}}+q(x)^{\left(\frac{x}{1-x}\right)^{2k-2}}$$

Now and it's a crucial idea we want something like :

$$\left(\frac{x}{1-x}\right)^{2k-2}\geq \left(\frac{1-(p(x)+\varepsilon)}{q(x)}\right)^y$$

AND :

$$\left(\frac{1-x}{x}\right)^{2k-2}\geq \left(\frac{1-q(x)}{p(x)+\varepsilon}\right)^y$$

Now it's not hard to find a such $y$ using logarithm .

We get someting like :

$$x^{\left(\frac{1-x}{x}\right)^{2k}}+(1-x)^{\left(\frac{x}{1-x}\right)^{2k}}\leq q(x)^{\left(\frac{1-q(x)}{q(x)}\right)^{y}}+(1-q(x))^{\left(\frac{q(x)}{1-q(x)}\right)^{y}}$$

Furthermore the successive iterations of this method conducts to $1$ because the values of the differents polynomials (wich are an approximation of the initial curve) tend to zero or one (as abscissa).

The extra-thing (and a little bit crazy) we can make an order on all the values.

My second question

Is it unusable as theoretical\practical method ?