The asker seems to have the basic idea of the argument down. However, this question is tagged solution-verification, thus I believe that the asker wants feedback on their argument. Other answers have provided alternative proofs of this results, but these seems not to really address the question of critiquing the proof or its presentation.

Definitions

The argument that you give is a little unclear, as you have not unambiguously defined the objects you are working with, nor how they are meant to fit together. In American high schools, the definitions given for trigonometric functions are usually in terms of right triangles, e.g. $\sin(\theta) = \text{opp}/\text{hyp}$, where $\text{opp}$ is the length of the side oppose the angle $\theta$ in a right triangle, and $\text{hyp}$ is the length of the hypotenuse of that triangle.

However, this is not the only way to define trigonometric functions. In other contexts, the trigonometric functions might be defined in terms of points on the unit circle, or as the solutions to certain differential equations, or by their Taylor series, or in terms of the complex exponential function, and so on.

I cannot emphasize this enough: definitions matter! Everything in mathematics comes down to applying arguments to well defined mathematical objects. Often, a single mathematical object can be defined in multiple (equivalent) ways. Proving results about these objects depends on a thorough understanding their definitions.

Logical Structure

The argument you give is also a little unclear as you don't indicate which statements follow from the others. For example, when you write

$\cos^2(\theta) + \sin^2(\theta) = 1$

$(\frac{b}{c})^2 + (\frac{a}{c})^2 = 1 $

what does this mean? Does the first line imply the second? Does the second imply the first? Are the two statements entirely unrelated? You should connect the ideas in some manner, either using English or notation.

Moreover, as I read your argument, you start by assuming the conclusion. This is no good. You need to start with a known true statement, then show how that implies the desired statement. Again, it is helpful to be careful about indicating how one statement relates to the next.

Grammatical Structure

Good mathematical writing should be easy to read, in the sense that you should be able to read it out loud, and it should make sense. For example, you ought to write in complete sentences, mixing in notation only when it makes it easier to understand what is going on.

With the above in mind, here is how I would present your proof:

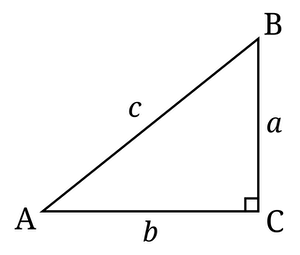

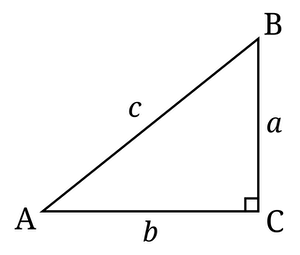

Definition: Let $\triangle ABC$ be an arbitrary right triangle, where $C$ is the right angle. Let $a$, $b$, and $c$ denote the lengths of the sides opposite the angles $A$, $B$, and $C$, respectively (see the image, above, taken from Wikipedia). Define the sine and cosine of the angle $A$ by

$$ \sin(A) = \frac{a}{c} \qquad\text{and}\qquad \cos(A) = \frac{b}{c}. $$

Proposition: If $0 < \theta < 90^{\circ}$, then $ \sin(\theta)^2 + \cos(\theta)^2 = 1$.

Proof: Using the notation in the definition above, set $\theta = A$.[1] Starting on the left-hand side of the desired identity, the definitions of sine and cosine give

$$ \sin(\theta)^2 + \cos(\theta)^2

= \left(\frac{a}{c} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{b}{c} \right)^2. $$

Expand this and simplify to get

$$ \left(\frac{a}{c} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{b}{c} \right)^2

= \frac{a^2}{c^2} + \frac{b^2}{c^2}

= \frac{a^2 + b^2}{c^2}. $$

The Pythagorean theorem[2] implies that $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$, and so

$$ \frac{a^2 + b^2}{c^2} = \frac{c^2}{c^2} = 1. $$

Combining these equalities gives

$$ \sin(\theta)^2 + \cos(\theta)^2 = 1, $$

as desired.

Addendum: As pointed out by fleablood in the comments, there is a slight hole in the argument: the definition of sine and cosine given above presupposes that the ratios don't depend on the actual triangle. That is, if $\triangle ABC$ and $\triangle A'B'C'$ are right triangles such that $A$ and $A'$ have the same measure, then

$$ \frac{a}{c} = \frac{a'}{c'}. $$

This follows immediately from properties of similar triangles, but probably requires some mention in the general development of the theory. Of course, once you make this observation, we could just assume that $c=1$. The Pythagorean theorem implies that $a^2 + b^2 = 1$, and so

$$ \sin(\theta)^2 + \cos(\theta)^2 = \left(\frac{a}{1}\right)^2 + \left( \frac{b}{1} \right)^2 = a^2 + b^2 = 1. $$

This argument is basically identical to the one given above, but the computations are slightly more straight-forward.

[1] Note that the assumption that $0 < \theta < 90^{\circ}$ is important here, as we have not defined the sine and cosine functions for other values of $\theta$. This is part of why we eventually define these functions using more sophisticated tools in more advanced settings.

[2] I am going to assume that the Pythagorean theorem has already been established, since the argument in the original question seems to assume this result. If one needs a proof, there are one or two on Cut the Knot.