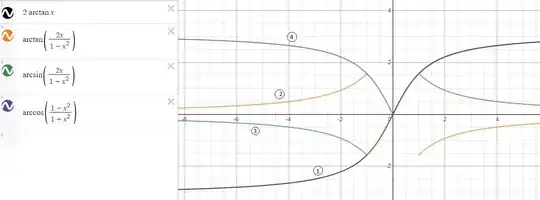

I have these three equations: $$2\arctan(x) = \arcsin(\frac{2x}{1+x^2}),\left |x\right|\leq1$$ $$2\arctan(x) = \arccos(\frac{1-x^2}{1+x^2}),x\geq0$$ $$2\arctan(x) = \arctan(\frac{2x}{1-x^2}),\left |x\right|<1 $$ I can verify these by simple substitution taking $x = \tan\theta$ for some $\theta$ but I could not understand why these conditions for $x$ are given. I can see their graphs makes sense but is there an algebraic way of proving/verifying these conditions?

-

Consider principal values of arc tan, arc sin, arc cos etc. – Koro Aug 25 '20 at 16:52

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inverse_trigonometric_functions#Principal_values – lab bhattacharjee Aug 25 '20 at 17:03

-

A very late comment: you can find interesting the surface graphics displayed here. – Jean Marie May 15 '21 at 10:33

3 Answers

An exercise I found helpful.

Consider the intersection of the line $y = tx$ and the circle $x^2 + y^2 = 2x$

The circle has radius 1 and is centered at $(1,0)$

$x^2 + (tx)^2 = 2x\\ x = \frac {2}{1+t^2}\\ y = \frac {2t}{1+t^2}$

Now lets translate everything one unit to the left. Yes, we could have calculated the intersection of $x^2+ y^2 = 1$ and the line $y = t(x+1)$ but the algebra is simpler this way.

$x = \frac {2}{1+t^2}-1\\ x = \frac {1-t^2}{1+t^2}\\ y = \frac {2t}{1+t^2}$

Do these equations look familiar? What are $x,y,t$ geometrically / trigonometrically?

The line and the circle and the x axis form an angle on the circle, which has half the measure of the central angle to that same arc.

$t = \tan \frac 12 \theta$

And of course,

$x = \cos \theta\\

y = \sin \theta$

Regarding the domain restrictions. If $t> 1$ the line $y = t(x+1)$ will be intersecting the circle in QII.

$\arcsin (\frac {2t}{1+t^2})$ will return a value corresponding to a point in QI

Similarly if $t < 0$

$\arccos (\frac {1-t^2}{1+t^2})$ will return a value for a point in QI or QII while our reference point is actually in QIII or QIV

I found this exercise to more helpful to build intuition than mechanically chug through the trig identities.

Here would be the mechanical approach:

$\sin (\arctan \frac {a}{b}) = \frac {a}{\sqrt {a^2 + b^2}}\\ \cos (\arctan \frac {a}{b}) = \frac {b}{\sqrt {a^2 + b^2}}\\ \theta = 2\arctan t\\ \sin \theta = 2\sin(\arctan t)\cos(\arctan t) = 2\frac {1}{\sqrt {1+t^2}}\frac {t}{\sqrt {1+t^2}} = \frac {2t}{1+t^2}\\ \cos \theta = \cos^2(\arctan t)-\sin^2(\arctan t) = \frac {t^2}{1+t^2} - \frac {1}{1+t^2}= \frac {1-t^2}{1+t^2}$

- 57,877

-

Really amazed by this intuitive explanation! Also I think the line intersecting the circle $x^2 +y^2 = 1$ should be $ y = t(x+1)$ instead of $ y = t(x-1)$? – asks281 Aug 26 '20 at 15:22

Hint: Further to my comment,

Let $\arctan x=\theta\implies \tan \theta=x$, where $ \theta \in (-\pi/2,\pi/2)$ Why? Because $\tan$ is invertible there. Isn't it?

$\sin 2\theta=\frac{2\tan\theta}{1+\tan^2\theta}=\frac{2x}{1+x^2}\tag{1}$

Note that $2\theta\in (-\pi,\pi)\implies$ we can't take inverse of $\sin $.

In order to take inverse of $\sin$, we should have $2\theta \in [-\pi/2,\pi/2]$, which is clearly true if $-\pi/4\le \theta\le \pi/4$ so that $x=\tan \theta \in [-1,1]$

Hence, if $2\theta\in [-\pi/2,\pi/2] $, then we can take inverse in $(1)$ to get:

$2\theta=\arcsin \frac{2x}{1+x^2}\implies 2\arctan x=\arcsin\frac{2x}{1+x^2}$, where $2\theta\in [-\pi/2,\pi/2]\implies |x|\le 1 $

Similarly, prove the rest of the two.

Response to comment: Definition of $\arcsin, \arctan$:

I have used principal values of arc sin, arc tan. That is to say, $\arcsin x=\phi$ if $x=\sin\phi$, where $\phi\in [-\pi/2,\pi/2]$

For tan, $\arctan y=\psi$ if $\tan\psi =y$, where $\psi\in [-\pi/2,\pi/2]$.

- 11,402

-

Not only is the function invertible, but you have to use the precise definition of arctan and arcsin, etc. The definition specifies the interval to which you've restricted tan, sin, etc., to take the inverse. – Ted Shifrin Aug 25 '20 at 17:18

The last equation says (by the definition of arctan) that if $\tan\theta=x$, then $\tan2\theta = \frac{2x}{1-x^2}$; so this is just the double-angle formula for tan.

The first two equations can be derived from the last equation by drawing a right triangle with sides $2x$ (opposite) and $1-x^2$ (adjacent) and hypotenuse $1+x^2$, and thereby noting that the angle whose tangent is $\frac{2x}{1-x^2}$ is the same as the angle whose sine is $\frac{2x}{1+x^2}$, which is the same as the angle whose cosine is $\frac{1-x^2}{1+x^2}$.

- 78,820

-

The OP said he/she had done this. What needs to be explained is the domain restrictions in the three cases. – Ted Shifrin Aug 25 '20 at 16:53