Complementing the other answers, I'd say:

tl;dr: $\rightarrow$ and $\Rightarrow$ are implications from different meta levels.

Personally, I learned (and I still am!) distinguishing meta levels the most when formalizing mathematics with the computer and proof assistants. Namely, there you are a) forced to formalize some meta levels on your own and b) you usually get some type checking errors when mixing up different meta levels.

Hence, I'd like to sketch four meta levels pertaining proof assistants, and on every level identify a form of implication. At first sight, this might seem as an extreme overkill for a student of your level, but perhaps you can still take home some (perhaps philoshopic?) messages even if you don't understand everything at once.

A proof assistant and a formalization therein may feature the levels below. Throughout the answer, I tried using standard terminology with the exception of the numbering of the levels. That has been totally made-up by me for the sake of this answer.

A system (Coq, Isabelle, MMT, ...)

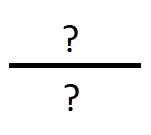

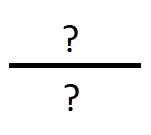

In the core of most proof assistants, judgements are used in the underlying implementation (in a programming language), to represent and compute that something that the user has entered is valid. For instance, you might imagine an "is-valid judgement". To infer such judgements, the system might use inference rules. You might think of them as functions in a programming language getting judgements as input and yielding judgements as output. Often, such rules can be pretty expressive; on pen-and-paper they are often denoted in the following form:

You can read this as: "if we inferred the thing above the line, then we can also infer the thing below the line." I will show a concrete rule in the next paragraph, but for now, it suffices to see this as a first form of implication.

In the following, I will draw further examples from the proof assistant Coq to substantiate my points, but rest assured that the concepts are sound and useful in general, too.

A mathematical foundation (usually some flavor of type theory or set theory)

To actually be able to do and write down anything, you need a foundation — without them there is simply nothing to draw from. In mathematics, foundations are often left implicit by working mathematicians (outside of logic that is), however, most would probably say that they work in ZF set theory. Likewise, a proof assistant also needs a foundation.

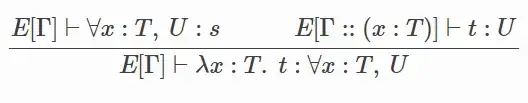

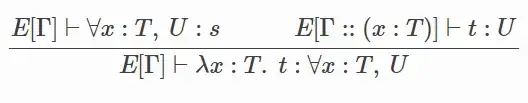

Foundations for proof assistants can often be conveniently stated with the rules discussed before. For instance, Coq uses the so-called calculus of constructions as its foundation. Here is an arbitrary rule from its documentation:

Don't worry — you don't have to understand or even parse all symbols. Let me just tell you that this rule (partly) implements functions. In other words, we need this rule among others so that end users using Coq can write functions (as in from programming languages) therein. And, you may believe me on that, functions correspond to yet another form of implication, although this time at the foundational level.

A logic (first-order logic, higher-order logic, modal logic, ...)

Now given a system and its foundation, we of course want to express theorems and proofs in a proof assistant. For that, we need a logic to work with. Note that the line between systems, foundations, and logics might be blurry depending on the system in use. Some systems hardcode foundations and logics whereas others such as MMT have foundation-independence as one of their main goals. With Coq, the shipped standard library comes equipped with some logic. For didactic reasons, let us simulate (re)implementing a logic in Coq and for simplicity, let us restrict to propositional logic (PL). Of course, PL is far too weak for anything useful. Nevertheless, in Coq this could look as follows:

Inductive PL :=

| impl: PL -> PL -> PL

| and: PL -> PL -> PL

| or: PL -> PL -> PL

| neg: PL -> PL.

Again, you don't need to understand the semantics of this in detail. It just says that we define a type called PL and for writing down things of PL we got 4 postulated constructors. For instance, if x is of PL, then we can write down impl x x (to represent $x \rightarrow x$). Concretely, per the code above, the constructor named impl takes two subformulae from PL itself and returns a new formula — again from PL (... -> PL). The same holds true for and and or. Last but not least, neg is a constructor taking only one formula as input and, as before, outputting a new formula.

Remember when you were taught propositional logic and were told that exactly those connectives exist, how many arguments they have, and how they can be combined? This is exactly it, just formalized in Coq.

The implication on this meta level is impl. This variant of implication might be the closest to what you would have understood as "implication" so far in your education. (This is not intended to sound condescending.)

A theory within the logic (e.g., a logic within a logic)

Let's assume we work a bit harder on the logic meta level and instead of propositional logic we formalize the more elaborate case of first-order logic (FOL). Then, within FOL we are free to formalize further things, e.g., PL itself. Note that by "PL" I mean the (philosophic?) concept of propositional logic and not the instantiation from the last point, which I typeset as PL. Concretely, PL can be seen as the FOL theory containing

- four function symbols:

impl', and', or' with arity 2, and neg' with arity 1,

- and various axioms, e.g.,

∀xyz. ¬(impl' x y = and' x y) (for those who understand: effectively demanding the function symbols to be constructors of an inductive data type).

Here evidently, impl' is (supposed to be) yet another form of implication — building upon the previous meta level from 3.

Let me come full circle with your question. First, you might imagine the implication from level 3 as $\Rightarrow$ and the one from level 4 as $\rightarrow$. Second, you asked which of the following notations is correct:

$$A = \{x\in \mathbb{R}\mid x^2 = 1 \rightarrow x\geq 0\}\\B = \{x\in \mathbb{R}\mid x^2 =1 \Rightarrow x\geq 0\}$$

This depends on which level you formalize what $\{\ldots\}$ is. If you formalize it on level numbered 3 above as something of the form $\{x \in \_ \mid x \Rightarrow y\}$ where $x$, $y$ themselves stem from level 3, too, then only variant $B$ is correct. But note that this implies that the expressions $x^2 = 1$ and $x \geq 0$ are from level 3 (PL), too!

If on the other hand $\{\ldots\}$ has been defined on the level numbered 4 above, only $A$ is correct. But then again, $x^2 = 1$ and $x \geq 0$ must be expressions of the fourth level (well-formed terms within the given FOL theory there).

As a last note, the requirements of where the subexpressions come from stated in the last two paragraphs are often relativized. For instance, for level-4-expressions $x, y$, it might make sense to speak of $x \Rightarrow y$ to mean "$y$ is derivable from $x$ via some application of level-4-rules". Sometimes, this is implies $x \rightarrow y$. Sometimes not. Hence, be cautious about mixing meta levels, especially when working in logics or formalizing them.

⟹'s purest (most direct) meaning is not that its consequent is derivable from its antecedent, but simply an assertion of the truth of its underlying material conditional.$\quad$2. Your set $B,$ i.e., ${x\in \mathbb{R}: x^2 =1 \implies x\geq 0}$ does make sense, just likeA⟹(B⟹C)andA and (B⟹C), where the symbol for even the non-main connective is metalogical rather than material; saying that $B$ is the set of reals that satisfy a conditional is not the same as actually asserting that that conditional is true.$\quad$3. I agree with the answers below.