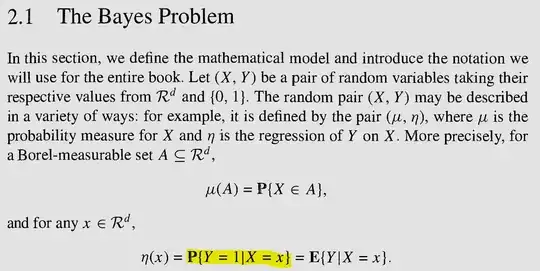

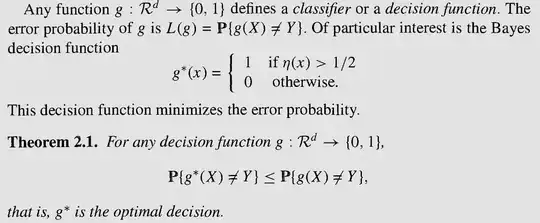

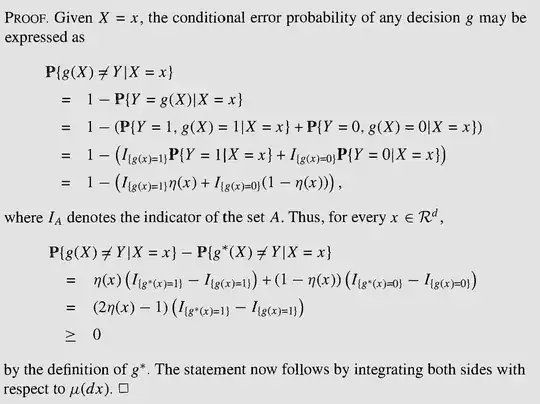

I'm reading about The Bayes Problem in textbook A Probabilistic Theory of Pattern Recognition by Devroye et al.

They make use of $\eta(x)=\mathbb{P}\{Y=1 \mid X=x\}$ throughout the proof.

In my understanding, the conditional probability $\eta(x)=\mathbb{P}\{Y=1 \mid X=x\}$ is defined only when $\mathbb P \{X=x\} > 0$. If $X$ is continuous, for example, $X$ follows normal distribution, then $\mathbb P[X=x]=0$ for all $x \in \mathbb R$. Then $\eta(x)$ is undefined for all $x \in \mathbb R$, confusing me.

Could you please elaborate on this point?