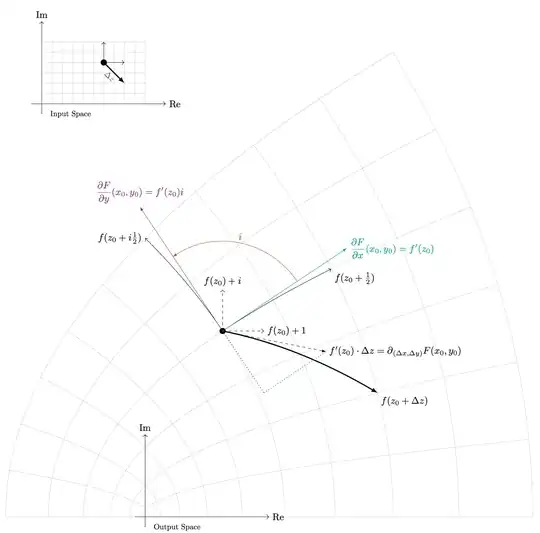

If $f(x + iy) = u(x,y) + i v(x,y)$, then $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$ describes how $f$ changes if we take take small step in the $x$-direction in the input space, and $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$ describes how $f$ changes if we take a small step in the $y$-direction in the input space.

I've been thinking of $f'(z_0)$ as the "guess" for how $f$ would change if we took the step $1+i0$ in the input space, since the guess is the derivative multiplied by the step. This, as is expected, coincides with how we expect $f$ to change when we move along the $x$-axis of the input space, i.e. $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$. Our guess for how $f$ would change if we took the step $0+i1$ in the input space would, similarly, coincide with $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$. Accordingly, $\frac{1}{i}\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$ describes how $f$ changes if we took a step in the $(\frac{1}{i})(0+i1) = 1+i0$ direction in the input space. Except not necessarily? I mean, for this to hold the Cauchy–Riemann Equations have to be satisfied, right? (E.g. the last line wouldn't work for $\operatorname{Re}:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{C}$.) But why? Where have we used them in this line of argument?

Also, intuitively, why does $$ \lim_{h\to 0} \frac{ f(z_0 + ih) - f(z_0) }{ ih } $$ equal $$ \lim_{h\to 0} \frac{f(z_0 + h) - f(z_0)}{ h }, $$ or, say, what does it, intuitively, mean for them to be equal? (No matter how you approach $z_0$ the derivative $f'(z_0)$ must stay the same, sure, but, is there something more visual or basic that one could use as intuition?)

Edit: A visual for $f(z) = z^2$:

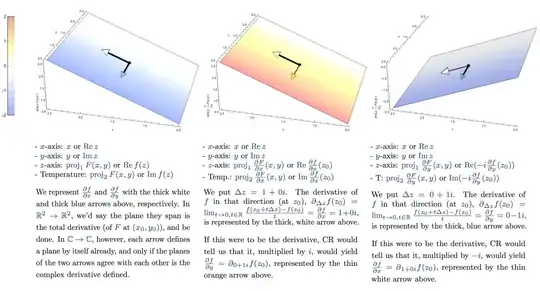

Edit 2: A different sort of visual, this time for $f(z)=\overline{z}$, with some text of me trying to understand it: