The standard geometric interpretation of complex numbers is to draw the complex plane by identifying the horizontal axis as the real axis and the vertical axis as the imaginary axis, so that the complex number $z = x + iy$ is identified with the point $(x, y)$. That is to say, a complex number is geometrically a point on the plane.

But we also know from the polar form of complex numbers that when we multiply two complex numbers $z=r(\cos \alpha + i \sin \alpha)$ and $w=s(\cos \beta + i \sin \beta)$ that we can “add the angles and multiply the distances” to get $zw=rs(\cos(\alpha + \beta) + i \sin(\alpha + \beta))$. That means we can view one of the complex numbers, say $z$, as being a linear map that performs a rotation and/or dilation on the other number (here $w$) which is viewed as a point, to return a new point.

In linear algebra though, a point is a vector $v \in V$, and a linear map is a function $T: V \to W$. These are two different kinds of objects, and it would be a type error to try to identify $v$ with $T$ somehow. So my question is something like, why does it work out that complex numbers can be viewed in two different ways even though that seems like a type error?

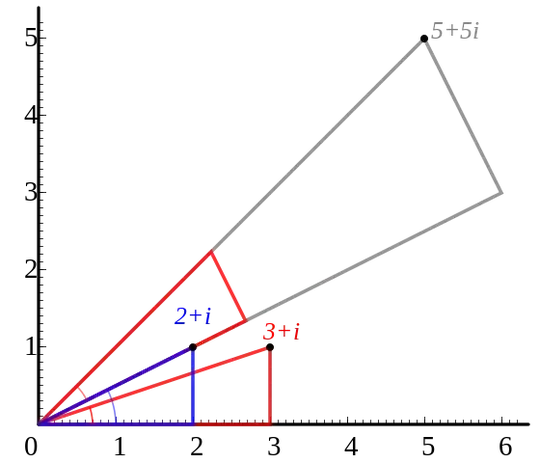

If I stopped here though I feel like people would just give me examples of other things in math where it's possible to view a single object through multiple geometric "lenses". (Maybe that is what I want, but I feel like there is still something to my original question.) So let me go a little further: Of course there are many situations where the same objects can be visually represented in different ways, e.g. a real number can be both a length and an area and a volume and so forth. And even in the case of real numbers, we can say that we start with some distance $x$, then multiply by a distance $y$ to get a distance $yx$. In that case, isn’t $y$ acting as a “linear map” $x \mapsto yx : \mathbf R \to \mathbf R$? That’s true, but we can also use similar triangles (figure from this book, p. 3) to show that $y$ can be seen as a length as well, so that $x$, $y$, and $yx$ are all lengths in a single figure. It’s this extra step that seems to be missing from the case of complex number multiplication.