Let $(E,d)$ be a metric space and $\Gamma\subseteq C_b(E)$ be bounded, i.e. $$c:=\sup_{f\in\Gamma}\left\|f\right\|_\infty<\infty,$$ and equicontinuous, i.e. $$\forall x\in E:\forall\varepsilon>0:\exists\text{neighborhood }N\text{ of }x:f(N)\subseteq B_\varepsilon(f(x)).$$

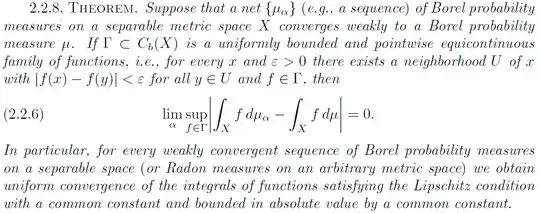

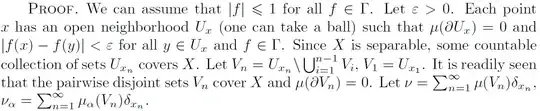

Let $(\mu_t)_{t\in I}$ be a net of probability measures on $\mathcal B(E)$ weakly converging to a probability measure $\mu$ on $\mathcal B(E)$.

Let $\varepsilon>0$. By assumption, for each $x\in E$, we can find an open neighborhood $N_x$ of $x$ such that $f(N)\subseteq B_\varepsilon(x)$, but why can we choose $N_x$ such that $\mu(N_x)=0$?

The claim is made in the proof of Theorem 2.2.8 in Bogachev's Weak Convergence of Measures:

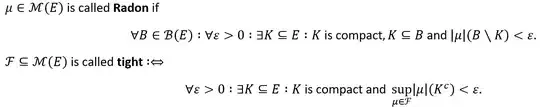

BTW: Can anyone explain to me how we obtain the claim for Radon measures on general metric spaces from the result of arbitrary measures on separable metric spaces? The definition of Radon is as follows: