How can $\lim\limits_{n\to\infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n^2} 1$ result into 1+3+5...? Why odd numbers?

-

4$\lim_{n \to \infty}$ doesn't "result" in $1 + 3 + 5 + \cdots$. The limit doesn't exist. – Caleb Stanford May 20 '13 at 01:54

-

2I mean, probably you are just talking about the partial sums, but if that's the case I don't understand why you put a limit sign there. – Caleb Stanford May 20 '13 at 01:55

-

@Goos as in Peter's context: http://math.stackexchange.com/questions/396810/explain-the-1-2-3-in-frac1-1-1-cdots1-2-3-cdots-lim – user8005 May 20 '13 at 01:57

-

Peter's context involves a limit of ratios of partial sums, not a ratio of limits of partial sums. – anon May 20 '13 at 01:59

-

@user8005 I think that 1+3+5.. expresion is understood to be a limit – Gaston Burrull May 20 '13 at 02:00

3 Answers

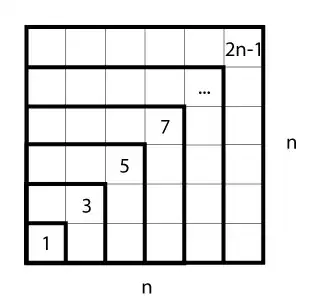

Hoo boy. You're in for a treat; this theorem was known to Pythagoras and his disciples.

Theorem: The sum of the first $n$ odd numbers is equal to $n^2$.

Proof: By picture.

The original image is part of a page containing two proofs of this identity: http://www.9math.com/book/sum-first-n-odd-natural-numbers. It is not mine.

- 18,793

-

1I like this proof, essentially is the telescopic sum argument $\sum (2k-1)=\sum [k^2-(k-1)^2]=n^2$ – Gaston Burrull May 20 '13 at 02:41

-

AoPS has another picture, not exactly this one: http://www.artofproblemsolving.com/Wiki/index.php/Proofs_without_words. – Gyu Eun Lee May 20 '13 at 02:46

-

$$1+3+5+\ldots+(2n-1)=\sum_{k=1}^n (2k-1)=\sum_{k=1}^n [k^2-(k-1)^2]=n^2-0^2=n^2=\sum_{k=1}^{n^2} 1$$

- 5,449

- 5

- 33

- 78

-

Does this definition have a name? Your response on Goos's the limit doesn't exist? – user8005 May 20 '13 at 01:54

-

@user8005 I don't know, its just a variant of this sum http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1_%2B_2_%2B_3_%2B_4_%2B_%E2%8B%AF – Gaston Burrull May 20 '13 at 01:55

-

@GastónBurrull Per your comment, regularization of divergent sums is a very tangential topic; I feel that bringing it up without clarifying the meaning of the original situation (see my comment above) with limits could be derailing. – anon May 20 '13 at 02:02

-

@anon I can only answer about partial sums, I think what OP means has nothing to do with the phenomenon to quantify divergent sums as http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1_%E2%88%92_2_%2B_3_%E2%88%92_4_%2B_%C2%B7_%C2%B7_%C2%B7 I think I'm ignorant about this other topic – Gaston Burrull May 20 '13 at 02:10

Note that the definition of summation $ \sum_{k=1}^m a_k $ $$ \sum_{k=1}^m a_k=a_1 +a_2+ \ldots +a_m. $$ So, for eachpositive integer $n$, we have $$ \sum_{k=1}^{n^2} 1=\sum_{k=1}^{n^2} (1+0k)=1+ 1+\ldots +1(n^2 {\rm times})=n^2. $$ On the other hand, for the same integer $n$, we have $$ {\rm sum\,\, of \,\,n-positive\,\, odd \,\,numbers}(=1+3+5+ \ldots+ (2n-1))=n^2. $$ Thus, we can write $$ \sum_{k=1}^{n^2} 1=1=3+5+\ldots+(2n-1) \tag 1 $$ Letting $n\to \infty$ in (1) we get the asked expression.

- 734

-

Wow, $1=1+0k$, I never saw before such a trick, probably would help me working with hard sums – Gaston Burrull May 20 '13 at 02:32