According to Wikipedia the convergence of the right hand side of: $$\frac{1}{\zeta(\frac{1}{2}+\epsilon)} = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{\mu(n)}{n^{(\frac{1}{2}+\epsilon)}}$$

for $\epsilon$ an arbitrary small number, is equivalent to the Riemann hypothesis.

The logarithm of the left hand side with $s$ instead $\frac{1}{2}$:

$$\log \left(\frac{1}{\zeta \left(s+\epsilon\right)}\right)$$

The derivative of that is:

$$\frac{\partial \frac{1}{\zeta (s+\epsilon)}}{\partial s}=-\frac{\zeta '(s+\epsilon)}{\zeta (s+\epsilon)^2}$$

Notice that according to Mathematica:

$$-\frac{\zeta '(s+\epsilon)}{\zeta (s+\epsilon)^2}=\lim_{c\to 1} \, \left(\frac{\zeta (c) \zeta (s+\epsilon)}{\zeta (c+s+\epsilon-1)}-\zeta (c)\right)$$

Therefore:

$$-\frac{\zeta '(s+\epsilon)}{\zeta (s+\epsilon)^2}+\zeta(1+\epsilon)=\frac{\zeta (1+\epsilon) \zeta (s+\epsilon)}{\zeta (1+\epsilon+s+\epsilon-1)}$$

Now by joriki's and GH from MO's proofs, for $s>1$ and $c>1$: $$\sum\limits_{k=1}^{\infty}\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{\varphi^{-1}(\gcd(n,k))}{n^c \cdot k^s} = \sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{\lim\limits_{z \rightarrow s} \zeta(z)\sum\limits_{d|n} \frac{\mu(d)}{d^{(z-1)}}}{n^c} = \frac{\zeta(s) \cdot \zeta(c)}{\zeta(c + s - 1)}$$

where: $$\varphi^{-1}(n)=\sum_{d \mid n}d\mu(d)$$

Therefore: $$\frac{\zeta (1+\epsilon) \zeta (s+\epsilon)}{\zeta (1+\epsilon+s+\epsilon-1)} = \sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{\lim\limits_{z \rightarrow s + \epsilon} \zeta(z)\sum\limits_{d|n} \frac{\mu(d)}{d^{(z-1)}}}{n^{1+\epsilon}} = \sum\limits_{k=1}^{\infty}\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{\varphi^{-1}(\gcd(n,k))}{n^{1+\epsilon} \cdot k^{s+\epsilon}}$$

We then set $s=\frac{1}{2}$ and $\epsilon=\frac{1}{p}$ and look for symmetry by solving:

$$\frac{\zeta \left(\frac{1}{2}+\epsilon\right) \zeta (1+\epsilon)}{\zeta \left(\frac{1}{2}+\epsilon+1+\epsilon-1\right)}=\frac{\zeta (x) \zeta (x)}{\zeta (x+x-1)}$$

for $x$. Unfortunately I can only solve this numerically in Mathematica for various values of smaller and smaller epsilons, and plot the result. But we know that $x>\frac{1}{2}$ and we can set a sufficiently high upper bound for $x$. In the program I use: $\frac{1}{2} < x \leq 120$

Mathematica 8.0.1:

(*start*)

Clear[x, p, epsilon, a, s, c];

Monitor[TableForm[a = Table[

epsilon = 1/p;

c = x /.

FindRoot[

Zeta[1/2 + epsilon]*

Zeta[1 + epsilon]/Zeta[1/2 + epsilon + 1 + epsilon - 1] ==

Zeta[x]*Zeta[x]/Zeta[x + x - 1], {x, 2 - 1/2, 1/2, 120},

WorkingPrecision -> 60], {p, 5, 100}]], p]

ListLinePlot[a, PlotRange -> {1/2, 3/2}]

(*end*)

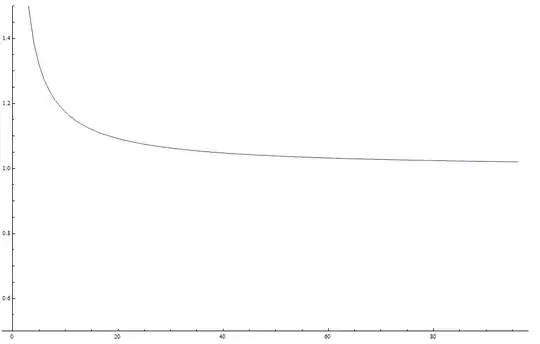

The plot of the function $x(p)$, with $\epsilon=\frac{1}{p}$, looks like this:

which clearly tends to $1$ as $p \rightarrow \infty$, and which would mean that we have absolute convergence for at least the second row and the second column in the now symmetric $\varphi^{-1}(\gcd(n,k))$ matrix and probably also all the other columns and rows since they are similar to alternating series like the second column and second row.

Question 1: Does the solution $$\lim_{\epsilon \to 0 } \, x(\epsilon)=1$$ tend to $1$ as the graph suggests?

In the the book "Convergence Methods for Double Sequences and Applications" by M. Mursaleen and S.A. Mohiuddine, Springer India 2014, there is on page 150 in the last chapter, the following Lemma 9.1:

"A double series $\sum_{k,l} a_{k,l}$ is absolutely convergenct if an only if the following [two] conditions hold:"

(i) There are $(k_{0},l_{0}) \in \mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}$ and $\alpha_{0} > 0$ such that: $$\sum\limits_{k=k_0}^{m} \sum\limits_{l=l_0}^{n}|a_{k,l}|\leq \alpha_{0} \text{ for all } (m,n) \geq (k_{0},l_{0})$$

(ii) Each row-series and each column-series are absolutely convergent.

My comment above was that (ii) probably already holds. So left is to show that (i) also holds. On page 156 the authors list Raabe's test applied to double series:

Theorem 9.11 (Raabe's test) Let $(a_{k,l})$ be a double sequence.

(i) Suppose that each row-series and each column-series corresponding to $\sum_{k,l} |a_{k,l}|$ are convergent. If there is $p>1$ such that

$$|a_{k,l+1}| \leq \left(1-\frac{p}{l}\right)|a_{k,l}| \text{ and } |a_{k+1,l}| \leq \left(1-\frac{p}{l}\right)|a_{k,l}|$$ whenever $k$ and $l$ are large, then $\sum_{k,l} |a_{k,l}|$ is convergent.

(ii) If $|a_{k,l+1}| \geq (1-\frac{1}{l})|a_{k,l}|>0$ for some $k \in \mathbb{N}$ and all large $l \in \mathbb{N}$, or if $|a_{k+1,l}| \geq \left(1-\frac{1}{k}\right)|a_{k,l}|>0$ for some $l \in \mathbb{N}$ and all large $k \in \mathbb{N}$, then $\sum_{k,l} |a_{k,l}|$ is divergent.

Part (i) in Raabes test above, I have computed as a limit for the second row and the second column, in Mathematica, and it seems to make sense. Part (ii) I have yet to explore.

Question 2: Does Raabe's test apply to all rows and columns in $\sum\limits_{k=1}^{\infty}\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{\varphi^{-1}(\gcd(n,k))}{n^c \cdot k^s}$, for $c>1$ and $s>1$?