In a case like this, I would pretend I was a high-school student and use the Rational Root Theorem, which says, here, that the only rational roots (if any) will be from the set $\{\pm1,\pm2,\pm4,\pm5,\pm10,\pm20,\pm25,\pm50,\pm100\}$.

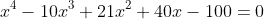

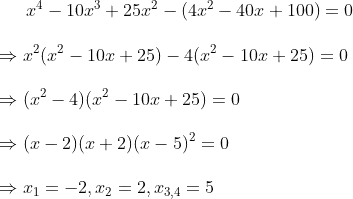

Starting systematically, you see that $\pm1$ aren’t roots, but $+2$ is. Then divide by $x-2$ to try to find the roots of $x^3-8x^2+5x+50$.

The RRT tells you to check $\{\pm1,\pm2,\pm5,\pm10,\pm25,\pm50\}$, and you already know that $\pm1$ are no good. Trying $+2$ is no good, but you try $-2$ and see that that’s a root too. And the quotient $(x^3-8x^2+5x+50)/(x+2)$ is $x^2-10x+25=(x-5)^2$, so that you’re done.

No ingenuity.

(In this very special case)

EDIT (addendum):

I notice that I originally omitted the possibilities $\pm20$ from the original list. I have included them now, but I might as well take the opportunity to adduce additional information:

If you know the magic of the Newton Polygon, you see that if you draw the two diagrams for the primes $2$ and $5$ and the original polynomial, both have their only vertices at $(0,2)$, $(2,0)$, and $(4,0)$. The only slopes are $-1$ and $0$. This means that a root can be only singly divisible by $2$ or $5$. In other words, the only possibilities are from $\{\pm1,\pm2,\pm5,\pm10\}$. You’d still need to do the computational work I did above, though.