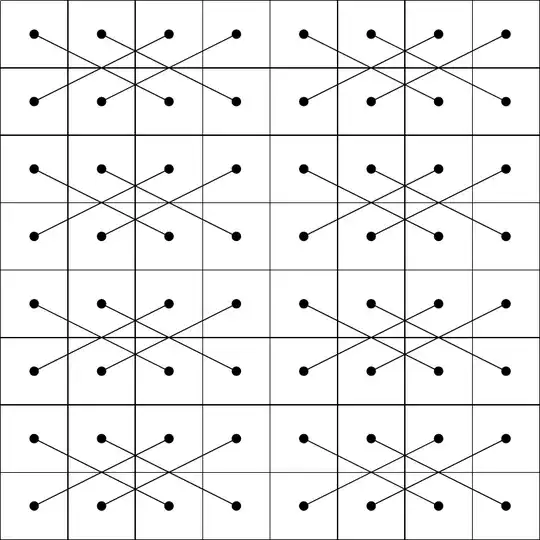

First of all, here is the proof that you can put no more than $32$ non-attacking knights on a chessboard. You can pair up the squares of the board into $32$ pairs, where each pair is a knight's move apart, as shown below.

Since you can place at most one knight in each pair, you can place at most $32$ knights.

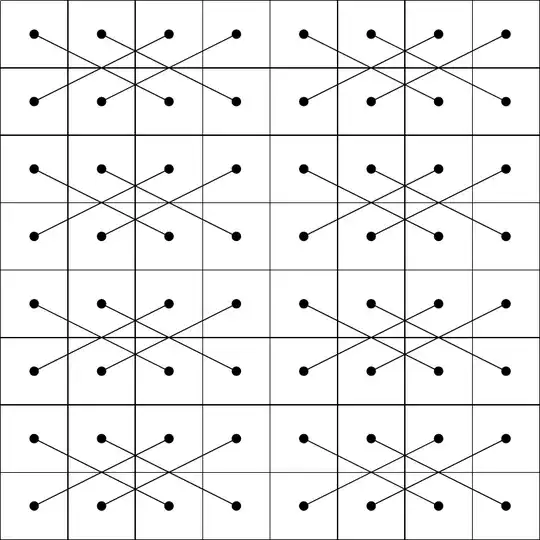

Now, imagine placing a queen on some square in this same diagram, and then placing an X on every square attacked by the queen, as well as an X on the squares a knight's move away from the queen. No matter where you place the queen, at least $4$ of these pairs will have both of their squares X'ed out. Therefore, the number of knights you can place is reduced by at least four, so you cannot place more than $28$ knights.

For example, when the queen is placed at $\mathrm A1$, the lower left corner, then the pairs $\mathrm {A1-C2, A2-C1,B2-D1}$, and $\mathrm{A4-C3}$ are all X'ed out (the letter is the column, and the number is the row). It is not too hard to verify case by case that the queen always X's out at least $4$ of these pairs. In fact, as the queen moves closer to the center, she X's out more pairs.