UPDATE: I realized the formula actually works fine (once I started using $2/r$ instead of $r$), but the mesh I was working with was not a perfect sphere to begin with, which led to skewed results, as you can see in the last screenshot I posted.

I'm trying to programmatically create a superellipsoid (specifically a "sphube") in a 3D program (Blender, using geometry nodes) for which I define the flattening.

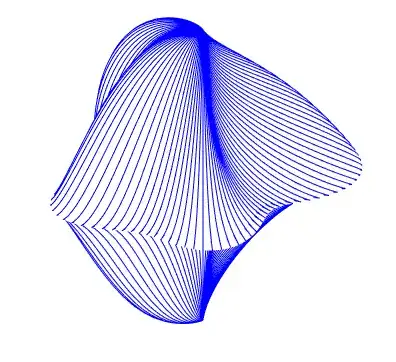

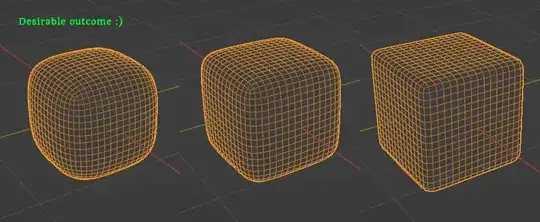

I want to end up with something resembling these:

[

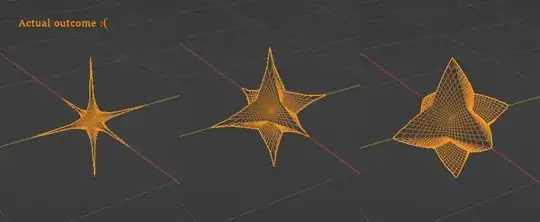

With the formula I came up with, I'm getting these instead:

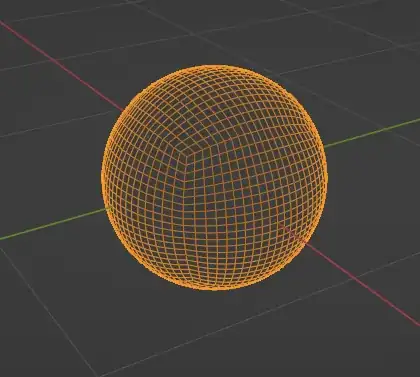

Let me walk you through my process. I start with a sphere with a radius of 1:

This is the formula I'm using to define the points on the surface of my sphube:

$$\lvert x\rvert^r + \lvert y\rvert^r + \lvert z\rvert^r = 1$$

Where x, y and z are the coordinates of each vertex and r is a real positive number (supposedly between 0 and 1) that controls the amount of flattening at the tips and the equator.

My thought process goes like this: I want to find a factor f with which to multiply each point's vector from the sphere's origin [0,0,0], so that each point lands on the sphube with the given flattening r. This is the formula I end up with:

$$(\lvert x\rvert * f)^r + (\lvert y\rvert * f)^r + (\lvert z\rvert * f)^r = 1$$

I solve for f as follows:

$$(\lvert x\rvert^r * f^r) + (\lvert y\rvert^r * f^r) + (\lvert z\rvert^r * f^r) = 1$$

I divide both sides by $f^r$ and switch sides:

$$\frac{1}{f^r} = \lvert x\rvert^r + \lvert y\rvert^r + \lvert z\rvert^r$$

I flip it (or whatever the correct term may be):

$$f^r = \frac{1}{\lvert x\rvert^r + \lvert y\rvert^r + \lvert z\rvert^r}$$

I take the r-th root:

$$f = \frac{1}{\sqrt[r]{\lvert x\rvert^r + \lvert y\rvert^r + \lvert z\rvert^r}}$$

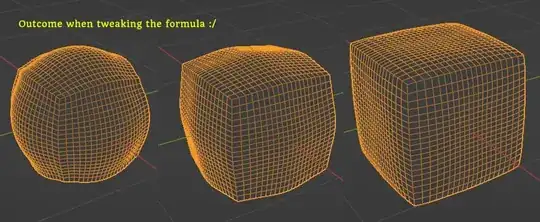

As mentioned above, I multiply each point of my initial sphere with the computed f, but get the star-like results shown above. Since the vectors are obviously going in the wrong direction, I tried dividing, instead, and I get this:

This is more like it, but the edges are pointed, instead of rounded, and the centers of the squares are bulged. And no value of r is giving me a perfect cube. So that can't be it either, can it?

Can anyone tell me where I'm going wrong? Or, alternatively provide me with a clean formula to map a sphere (or a cube) to a sphube (even if it worked correctly, the method I'm using will result in skewed vertices towards the edges)?

Thanks!