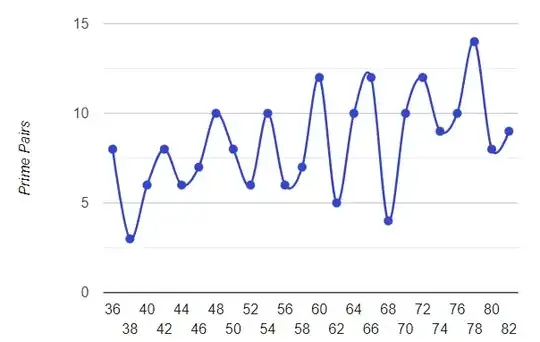

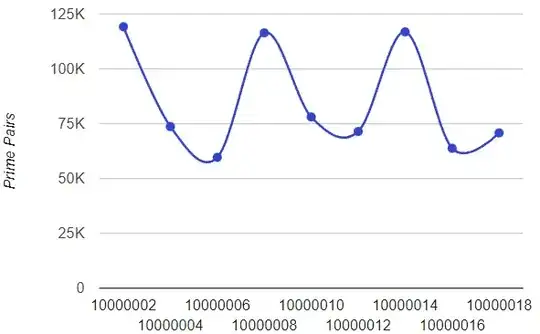

Noticed a pattern for $n \geq 6$, the number of prime pairs $(p,q)$ where $p+q=6n$, is always greater than the pairs for $6n+2$ and $6n+4$.

For example, when $n=6$

$36$ has $8$ prime pairs

(5,31) (7,29) (13,23) (17,19) (19,17) (23,13) (29,7) (31,5)

$38$ has $3$ prime pairs

(7,31) (19,19) (31,7)

$40$ has $6$ prime pairs

(3,37) (11,29) (17,23) (23,17) (29,11) (37,3)

The charts below show peaks for $6n$ and troughs for $6n+2$ and $6n+4$

This pattern seems to continue indefinitely ...

Question

Does this pattern hold true for all $6n$ peaks?