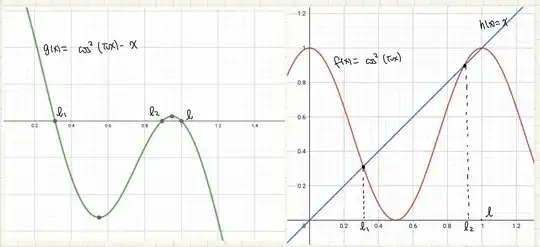

It suffices for iteration purposes to restrict $f$ to $[0,1]$ as $f(.) \in [0,1]$.

Set

$$A:= \{x: x\in[0,1], \exists n \in \mathbb{N};\text{ } f^{n}(x) \in (l_{2},1]\} $$

where $l_{2}$ is the second largest fixed point of $f$ (which is roughly $0.89$). If $A$ has measure $1$ then almost all points converge to $1$, this fact has been discussed by people before me. $\textbf{Assume}$ for the sake of contradiction that $m(A) < 1$.

$\textbf{Definition 1:}$ When $V \subset [0,1]$ and $n \in \mathbb{N}$ then

$$f^{n}(V) := \{y: \exists x \in V\text{ so that } y = f^{n}(x)\}$$

$$f^{-n}(V) := \{z: f^{n}(z) \in V\}$$

Note that $[0,1] = A \cup B$ where

$$B=\bigcap_{j=1}^{\infty}f^{-j}([0,l_{2}]).$$ Observe that $f^{-n-1}([0,l_{2}]) \subseteq f^{-n}([0,l_{2}])$ for all $n \geq 1$, indeed if $x \in f^{-n-1}([0,l_{2}])\cap (f^{-n}([0,l_{2}]))^c$ then $f^{n}(x) > l_{2}$ and therefore $f^{n+1}(x) > l_{2} \notin [0,l_{2}]$ which is impossible.

Getting our hands dirty we can verify that $[0,l_{2}] \subseteq [0,0.9]$, $f^{-1}([0,l_{2}]) \subseteq [0.1, 0.9]$ and $f^{-2}([0,l_{2}]) \subseteq f^{-1}([0.1,0.9]) \subseteq [0.1,0.4] \cup [0.6,0.9].$

Thus $B \subseteq [0.1,0.4] \cup [0.6,0.9]$, furthermore

$$B = \bigcap_{j=1}^{\infty}f^{-j}([0.1,0.4] \cup [0.6,0.9]).$$

Set

$$C = [0.1,0.4] \cup [0.6,0.9].$$

On $C$ we have $1.84 \leq |f'(.)| \leq \pi$. Furthermore like before we have $f^{-n-1}(C) \subseteq f^{-n}(C)$, indeed if $x \in f^{-n-1}(C) \cap (f^{-n}(C))^{c} $ then $f^n(x) \not \in C$ and $f^{n+1}(x) \not \in C$ which is impossible.

Since we know that $m(A) < 1$ and $m(A)+m(B) = 1$, it follows that $m(B)>0$.

$\textbf{Claim 1:}$ $$m(f^{-n}(C)) \rightarrow m(B).$$

$\textbf{Proof:}$ Note that the characteristic functions $1_{f^{-n}(C)}(.)$ decrease downward to $1_{B}(.)$ (as $n\rightarrow \infty$). Thus by the monotone convergence theorem we have that $$\int_{0}^{1}1_{f^{-n}(C)}(x)dx \rightarrow \int_{0}^{1}1_{B}(x)dx = m(B).$$

$$\Rightarrow m(f^{-n}(C)) \rightarrow m(B).$$

$\textbf{Definition 2:}$ For an interval $I \subseteq [0,1]$ with non empty interior, define

$$P_I := \frac{m(A\cap I)}{|I|} = \frac{m(A\cap [a,b])}{b-a} = \frac{\int_{I}1_{A}(x) dx}{|I|}$$

where $I = [a,b]$.

$\textbf{Definition 3:}$ For an interval $[a,b] \subseteq [0,1]$ we set $T((\gamma_{j})_{j=1}^{n}, [a,b])$, where $\gamma_{j} \in \{0,1\}$ as follows: if $n = 1$ then

$T((\gamma_{j})_{j=1}^{1}, [a,b]) = \begin{cases} f^{-1}([a,b])\cap[0,\frac{1}{2}] & \text{ if }\gamma_{1} = 0 \\

f^{-1}([a,b]) \cap[\frac{1}{2},1] & \text{ if }\gamma_{1} = 1

\end{cases}$

and for $n > 1$ we define

$$T((\gamma_{j})_{j=1}^{n}, [a,b])= T((\gamma_{j})_{j=2}^{n},T((\gamma_{k})_{k=1}^{1}, [a,b]))$$

$\textbf{Example 1:}$ $T((0,1),[0,1]) = T((1), T(0,[0,1]))= T((1),[0,\frac{1}{2}])= [\frac{1}{2},\frac{3}{4}]$

$\textbf{Observation 1:}$ $f^{-n}([a,b])$ is a union of $2^n$ disjoint closed intervals, each of the form $T((\gamma_{j})_{j=1}^{n}, [a,b])$ for some sequence $(\gamma_{j})_{j=1}^{n} \in \{0,1\}^{n}$

$\textbf{Lemma 1:}$ $$\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty}\min( \min_{V \in \{0,1\}^{n}}P_{T(V,[0.1,0.4])}, \min_{V \in \{0,1\}^{n}}P_{T(V,[0.6,0.9])}) = 0$$

$\textbf{Proof:}$ Suppose that there exists a sequence of naturals $n_{1}< n_{2},...$ and an $\alpha > 0$ so that

$$\min( \min_{V \in \{0,1\}^{n_{j}}}P_{T(V,[0.1,0.4])}, \min_{V \in \{0,1\}^{n_{j}}}P_{T(V,[0.6,0.9])}) \geq \alpha,$$

then for such $n_{j}$ note that

$$f^{-n_{j}}(C) = \bigcup_{V \in \{0,1\}^{n_{j}}}T(V,[0.1,0.4]) \cup \bigcup_{W \in \{0,1\}^{n_{j}}}T(W,[0.6,0.9])$$

a union of $2^{n_{j}+1}$ intervals, if each such interval $U$ had $P_{U} \geq \alpha$ then we have the inequality;

$$m(B) \leq m(f^{-n_{j}}(C))(1-\alpha)$$

Taking limits as in claim $1)$ we have

$$m(B) \leq m(B)(1-\alpha),$$

which is only possible when $\alpha = 0$ or $m(B) = 0$, as $m(B) \neq 0$ we have a contradiction.

$\textbf{Lemma 2:}$ If $I$ is a subinterval of $C$ (which is $[0.1,0.4] \cup [0.6,0.9]$) then when $\gamma \in \{0,1\}$, $T((\gamma), I)$ has length between $\frac{|I|}{\pi}$ and $\frac{|I|}{1.84}$.

$\textbf{Proof:}$ $T((0),I)$ and $T((1),I)$ are two distinct intervals with the same size (as $T((1),I) = 1 - T((0),I)$). If $f([u,v]) = I$ where $u,v \geq \frac{1}{2}$ then $f([u,v])= [\cos^2(\pi u), \cos^2(\pi v)]$ (here $[u,v]$ corresponds to $T((1),I)$). Thus $|f([u,v])| = |f'(\eta)||u-v|$ for some $\eta \in [u,v]$. On $C$ we have $1.84 \leq |f'(\eta)| \leq \pi$. Thus $$1.84 |T((\gamma),I)| \leq |I| \leq \pi |T((\gamma),I)|.$$

$\textbf{Definition 4:}$ Given an interval $I \subseteq [0,1]$ we set $M_{I} := \sup_{x \in I}|f'(x)|$ and $m_{I} := \inf_{x \in I}|f'(x)|$.

$\textbf{Observation 2:}$ We have $M_{I}-m_{I} \leq 2\pi^2 |I|$ by the mean value theorem applied to $f'(.)$.

$\textbf{Lemma 3:}$ $$P_{I} \leq \frac{M_{T((\gamma),I)}}{m_{T((\gamma),I)}}P_{T((\gamma),I)}$$

$\textbf{Proof:}$ As before suppose $f([u,v]) = I$ where $u,v \geq \frac{1}{2}$ (as by symmetry $m([u,v]\cap A) = m([1-u,1-v] \cap A)$). Note here that $T((1),I) = [u,v]$. Observe that

$$P_{I} = \frac{\int_{I}1_{A}(x)dx}{|I|}$$

$$=\frac{\int_{u}^{v}1_{A}(\cos^2(\pi x))\pi \sin(2\pi x) dx}{|I|} \text{(by integration by substitution)}$$

$$= \frac{\int_{u}^{v}1_{A}(x)\pi \sin(2\pi x) dx}{|I|} \text{ (note that }1_{A}(\cos^2(\pi x))=1_{A}(x))$$

$$\leq \frac{M_{[u,v]}\int_{u}^{v}1_{A}(x)\,dx}{|I|}$$

$$= \frac{M_{[u,v]}P_{[u,v]}|v-u|}{|I|}$$

$$\leq \frac{M_{[u,v]}P_{[u,v]}|v-u|}{m_{[u,v]}|v-u|} \text{ (by M.V.T)}$$

$$= \frac{M_{T((1),I)}P_{T((1),I)}}{m_{T((1),I)}}$$

the case for $\gamma = 0$ is symmetrical.

$\textbf{Observation 3:}$ If $I \subseteq C$ ($I$ is a closed connected interval), we have by lemma 2 that

$$P_{I} \leq \frac{1.84 + 2\pi^2|T((\gamma),I)|}{1.84}P_{T((\gamma),I)} \leq (1 + \frac{2\pi^2 |I|}{1.84^2})P_{T((\gamma),I)}$$. By induction and lemma 2, we gather that

$$P_{I} \leq (\prod_{j=0}^{n-1}(1+\frac{2\pi^2|I|}{1.84^{j+2}}))P_{T((\gamma_{j})_{j=1}^{n},I)}$$

Note that $\sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \frac{2\pi^2|I|}{1.84^{j+2}} < \infty$ thus

$\prod_{j=0}^{\infty}(1+\frac{2\pi^2|I|}{1.84^{j+2}}) = K_{I} < \infty.$

Now set $C_{1} = [0.1, 0.4]$ and $C_{2} = [0.6,0.9]$, as per lemma 1) there exists $i \in {1,2}$ ,a natural number sequence $n_{1}<n_{2}<...$, and a sequence of sequences $(V_{j})_{j=1}^{\infty}$, with $V_{j} \in \{0,1\}^{n_{j}}$ so that $P_{T(V_{j}, C_{i})} \leq \frac{1}{j}$. Thus we must have $P_{C_{i}} \leq \frac{K_{C_{i}}}{j}$ for all $j \in \mathbb{N}$ or $P_{C_{i}} = 0$, but this is impossible as we have $m(C_{i}\cap A) > 0 $ for $i = 1,2$.