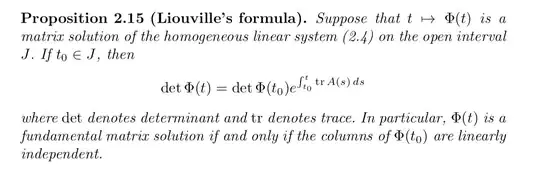

I am trying to understand the follwing equation in the proof below:

I tried to look at the case $n=2$.

What I get is $$\det(\Phi(I+tA))=\det( (I+tA)\Phi)+\text{very messy terms involving } o(t).$$

My guess/hope is that there are some arithmetic rules for "little-oh" I am not aware of that show that the last part is also $o(t)$.

Is there a book where this formula is shown. I couldn't find anything.

Many thanks in advance!