Addendum-1 added to respond to the comment/question of Jacob Martina.

Responding as followup on the comment already given by Anne Bauval, since no one else has explicitly shown the calculations. Also, responding because Covid questions get answers as clear as I can make them.

There are two ways of getting $n$ consecutive positive results. Either:

because the patient has the disease and has gotten $n$ consecutive true positives.

The probability of this happening is

$\displaystyle A = \left[ ~10^{-6} ~\right] \times \left[ ~(0.99)^n ~\right].$

because the patient does not have the disease and has gotten $n$ consecutive false negatives.

The probability of this happening is

$\displaystyle B = \left[ ~1 - 10^{-6} ~\right] \times \left[ ~(1 - 0.93)^n ~\right].$

Then, the conditional probability that the person has Covid, given the premises of the problem, including the premise that the person had $~n~$ consecutive positive results is

$$\frac{A}{A + B} $$

$$= \frac{\left[ ~10^{-6} ~\right] \times \left[ ~(0.99)^n ~\right]}{\left\{ ~\left[ ~10^{-6} ~\right] \times \left[ ~(0.99)^n ~\right] ~\right\} + \left\{ ~\left[ ~1 - 10^{-6} ~\right] \times \left[ ~(1 - 0.93)^n ~\right] ~\right\}}$$

$$= \frac{\left[ ~10^{-6} ~\right] \times \left[ ~(0.99)^n ~\right]}{\left\{ ~\left[ ~10^{-6} ~\right] \times \left[ ~(0.99)^n ~\right] ~\right\} + \left\{ ~\left[ ~999999 \times 10^{-6} ~\right] \times \left[ ~(0.07)^n ~\right] ~\right\}}$$

Addendum

The above approach merely represents the Mathematical attack given by the problem constraints. In reality, it is highly unlikely that Covid tests are independent of each other. So, you have to take the above computations with a huge grain of salt.

Addendum-1

Responding to the comment/question of Jacob Martina.

How can we know the wanted probability is $~\dfrac{A}{A+B}~$ and the denominator is not squared, (as in) $~\dfrac{A}{(A+B)^2}.~$

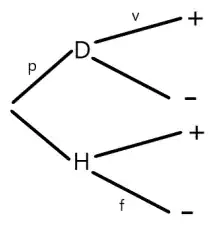

To answer this question, I will need to stretch your intuition. First, consider the following diagram.

In the diagram, the enclosed rectangle represents the Universe, and the two circles represent events $~E_1~$ and $~E_2.~$ Now, consider two questions:

Based on the diagram, what is the physical representation of the probability of event $E_2$ occurring?

Answer : It is the fraction

$~~\displaystyle \frac{\text{Area of the circle}~E_2}{\text{Area of rectangle} ~\textit{Universe}}.$

Based on the diagram, what is the physical representation of the probability of event $(E_2|E_1)$ occurring, which represents the probability of event $~E_2~$ occurring, under the assumption that event $~E_1~$ has occurred?

Answer : It is the fraction

$~~\displaystyle \frac{\text{Area of the intersection}~E_1 \cap E_2}{\text{Area of the circle}~E_1}.$

The point of the bullet point questions/answers is to stretch your intuition, around these ideas.

The mathematical equation that represents the answer to second bullet point question above is

$$\displaystyle p(E_2|E_1) = \frac{p(E_2 \cap E_1)}{p(E_1)}.$$

Before you proceed further, reviewing this section of my answer, I suggest you read the Wikipedia - Conditional Probability. Note that this Wikipedia article uses the variable $~A~$ to represent event $~E_2~$ and the variable $~B~$ to represent $~E_1.$

Now, please refer back to the diagram. Using my variables, $~E_2~$ and $~E_1,~$:

Let $~A~$ denote the probability of the events $~E_1~$ and $~E_2~$ both occurring.

That is, $~A = p(E_1 \cap E_2).~$

Let $~B~$ denote the probability of the events $~E_1~$ and $[\neg E_2]~$ both occurring.

That is, $~B = p(E_1 \cap [\neg E_2]).~$

This implies that $~p(E_1) = A + B.$

This explains why

$$p(E_2 ~| ~E_1) = \frac{p(E_1 \cap E_2)}{p(E_1)} = \frac{A}{A+B}.$$

Now, it remains to interpret the problem, so as to find a convenient choice, for events $~E_1~$ and $~E_2.$

You are given that $~n~$ consecutive positive results have occurred. You are then asked for the probability that the patient has the virus.

So, I let :

Therefore, I am being asked to compute $~p(E_2 ~| ~E_1).$

If you review the start of my answer, you will see that I am (in effect) letting:

This explains my computation $~\dfrac{A}{A + B}.$