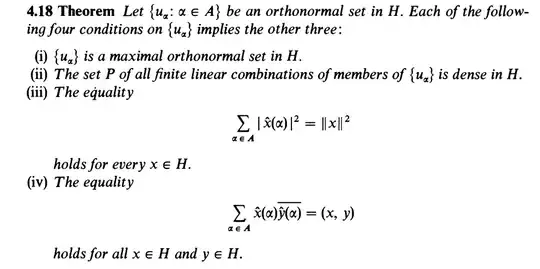

I am working through Walter Rudin's Real and Complex Analysis and I'm having trouble understanding something about Theorem 4.18:

I understand the proof of the theorem, but I'm confused about the relationship between conditions (i) and (ii). If $ \{u_\alpha\}$ is a maximal orthonormal set in H, that means that there are no extra vectors in H that we can add to $ \{u_\alpha\}$ which is orthogonoal to every vector in $ \{u_\alpha\}$. For example, $R^3$ equipped with the dot product is a Hilbert space, and $\{u_\alpha\}=\{(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)\}$ would be a maximal orthonormal set in $R^3$. But in this case, the set of all finite linear combinations of members of $\{u_\alpha\}$ would not just be dense in H, but is equal to H. My question is, wouldn't this be the case for every Hilbert space, and if not, could someone provide a good example to help build intuition as to how that works?