$$\Large{ \text{Introduction} }$$

I'm interested in solving methods for fractional-differential-equations (FDEs) without specifying the nature of the fractional derivatives. In doing so, I keep coming across the method of applying the Laplace transformation to the FDE, since this can help enormously with linear FDEs. In the papers, they always define the Laplace transformation of a function that is derived fractionally differently (not only differently depending on the type of operator, but also just like that). It occurred to me that it would be nice to define a fractional derivative operator using the Laplace transform. However, when I try to do this, I run into problems.

$$\text{My Idea}$$

While reading A comparative study of the fractional oscillators I got the idea that I could use Laplace transforms for an older problem related to solving certain FDEs (Solving the Fractional Differential Equation $\alpha \cdot \operatorname{D}^{2 \cdot v} \left( y\left( x \right) \right) + \beta \cdot \operatorname{D}^{v} \left( y\left( x \right) \right) + \gamma \cdot y\left( x \right) = f\left( x \right)$ - my answer here). I came up with a formula:

A fractional differential operator $\operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}$ is to be found, with the relation $\operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{n} = \frac{\operatorname{d }^{n}}{\operatorname{d}x^{n}} \wedge n \in \mathbb{N} \cup \left\{ 0 \right\} = \mathbb{W}$ aka it's the $\alpha$th derivative of a function with respect to $x$, using the Laplace transformation $\mathcal{L}$.

Let us define $\operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{n}\left[ y\left( x \right) \right] \operatorname{\mid}\limits_{x \to 0^{-}} : = y_{n,\, 0}$ and combine that with what we know: $$\mathcal{L}_{x}\left\{ \operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{n}\left[ y\left( x \right) \right] \right\}\left( s \right) = s^{n} \cdot \mathcal{L}_{x}\left\{ y\left( x \right) \right\}\left( s \right) - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{n}\left[ s^{n - k} \cdot y_{k - 1,\, 0} \right]$$ It follows: $$\operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{n}\left[ y\left( x \right) \right] = \mathcal{L}_{s}^{-1}\left\{ s^{n} \cdot \mathcal{L}_{x}\left\{ y\left( x \right) \right\}\left( s \right) - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{n}\left[ s^{n - k} \cdot y_{k - 1,\, 0} \right] \right\}\left( x \right)$$

Since the sum is only defined for natural $n$, it follows that we cannot simply substitute under complex $\alpha$. Let's just define a function $f$ for this, which has the property: $\mathbb{R} \mapsto \mathbb{Z}$ ... So $\left| f\left( \left| x \right| \right) \right| := \left| f \right|\left( x \right) \in \mathbb{W} \wedge x \in \mathbb{C}$, with the fundamental property $f\left( n \right) = n \wedge f\left( a \right) \ne a \wedge f\left( a - b \right) \leq f\left( a \right) \leq f\left( a + b \right) \wedge n \in \mathbb{W} \not\ni a \wedge 0 \leq b \in \mathbb{R}$.

With this we can define $\operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}$: \begin{align*} \operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}\left[ y\left( x \right) \right] &= \mathcal{L}_{x}^{-1}\left\{ s^{\alpha} \cdot \mathcal{L}_{x}\left\{ y\left( x \right) \right\}\left( s \right) - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\left| f \right|\left( \alpha \right)}\left[ s^{\alpha - k} \cdot y_{k - 1,\, 0} \right] \right\}\left( x \right)\\ \end{align*}

During trail and error, $\left| f \right|\left( x \right) = \operatorname{round}\left( \left| x \right| \right)$ was that what came closest to reality.

$$\Large{ \text{Problem} }$$

Of course I checked the operator for correctness, e.g. it is correct for $x^{n}$:

$ \operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}\left[ x^{n} \right] = \mathcal{L}_{x}^{-1}\left\{ s^{\alpha} \cdot \mathcal{L}_{x}\left\{ x^{n} \right\}\left( s \right) - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\left| f \right|\left( \alpha \right)}\left[ s^{\alpha - k} \cdot y_{k - 1,\, 0} \right] \right\}\left( x \right) = \mathcal{L}_{x}^{-1}\left\{ s^{\alpha} \cdot n! \cdot s^{-n - 1} - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\left| f \right|\left( \alpha \right)}\left[ s^{\alpha - k} \cdot y_{k - 1,\, 0} \right] \right\}\left( x \right) = \mathcal{L}_{x}^{-1}\left\{ s^{\alpha - n - 1} \cdot n! - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\left| f \right|\left( \alpha \right)}\left[ s^{\alpha - k} \cdot y_{k - 1,\, 0} \right] \right\}\left( x \right) = \mathcal{L}_{x}^{-1}\left\{ s^{\alpha - n - 1} \cdot n! \right\}\left( x \right) - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\left| f \right|\left( \alpha \right)}\left[ \mathcal{L}_{x}^{-1}\left\{ s^{\alpha - k} \cdot y_{k - 1,\, 0} \right\}\left( x \right) \right] = \frac{n!}{\Gamma\left( n - \alpha + 1 \right)} \cdot x^{n - \alpha} - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\left| f \right|\left( \alpha \right)}\left[ \mathcal{L}_{x}^{-1}\left\{ s^{\alpha - k} \cdot y_{k - 1,\, 0} \right\}\left( x \right) \right] = \frac{n!}{\Gamma\left( n - \alpha + 1 \right)} \cdot x^{n - \alpha} - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\left| f \right|\left( \alpha \right)}\left[ \mathcal{L}_{x}^{-1}\left\{ s^{\alpha - k} \cdot 0 \right\}\left( x \right) \right] = \frac{n!}{\Gamma\left( n - \alpha + 1 \right)} \cdot x^{n - \alpha} - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\left| f \right|\left( \alpha \right)}\left[ \mathcal{L}_{x}^{-1}\left\{ 0 \right\}\left( x \right) \right]\\ = \frac{n!}{\Gamma\left( n - \alpha + 1 \right)} \cdot x^{n - \alpha} - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\left| f \right|\left( \alpha \right)}\left[ 0 \right] = \frac{n!}{\Gamma\left( n - \alpha + 1 \right)} \cdot x^{n - \alpha} - 0 = \frac{n!}{\Gamma\left( n - \alpha + 1 \right)} \cdot x^{n - \alpha} $

But for other functions like $e^{n \cdot x}$, it comes out weirdly like this: $$ \begin{align*} \operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}\left[ e^{n \cdot x} \right] &= e^{n \cdot x} \cdot n ^{\alpha} \cdot \left( \frac{\alpha \cdot \Gamma\left( -\alpha,\, n \cdot x \right)}{\Gamma\left (-\alpha + 1 \right)} + 1 \right) - \sum\limits_{k = 1}^{\operatorname{round}\left( \alpha \right)}\left(\frac{1}{\Gamma\left( k - \alpha + 1 \right)} n^{\alpha} \cdot x^{k - \alpha - 1} \right) \end{align*} $$

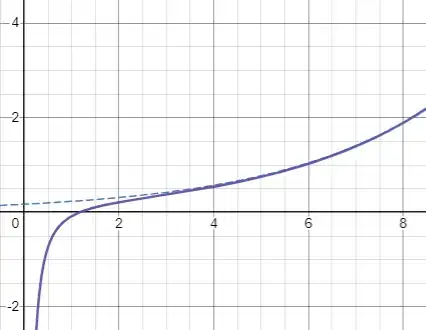

A plot of this for $\alpha = 2 \wedge n = 0.3$ ($\color{Purple}{\operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}\left[ e^{n \cdot x} \right]} \wedge \color{Blue}{\frac{\operatorname{d}^{2}}{\operatorname{d}x^{2}} e^{n \cdot x}}$) - desmos:

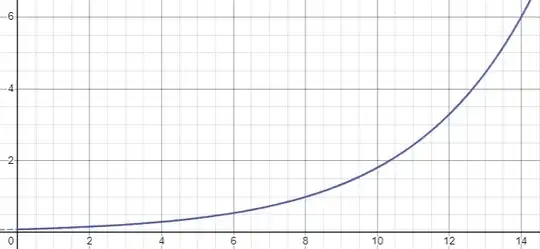

But ignoring the sum term gives a much better representation of reality:

Why? What is wrong here?

The sum term has to be there, scince $\operatorname{D}\limits_{x}^{n}\left[ e^{a \cdot x} \right] \operatorname{\mid}\limits_{x \to 0^{-}} = a^{n} \cdot e^{a \cdot x} \operatorname{\mid}\limits_{x \to 0^{-}} = a^{n} \cdot e^{a \cdot 0} = a^{n} \cdot e^{0} = a^{n} \cdot 1 = a^{n} \ne 0 \wedge a \ne 0$!

However, if I try to define it using series expansions: $$ \begin{align*} e^{x} &= \sum\limits_{k = 0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{k} \cdot x^{k} \right]\\ \implies \operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{n}\left[ e^{a \cdot x} \right] &= \sum\limits_{k = 0}^{\infty}\left[ \frac{1}{\Gamma\left( n - \alpha + 1 \right)} \cdot x^{k - \alpha} \right]\\ \end{align*} $$

Which in turn is something else.

As far as I can see, $\operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}$ is the same as $\operatorname{^{C}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}$ and $\operatorname{_{b}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}$ (the Caputo and Riemann–Liouville fractional derivative) when we differentiate a function with over a formal power series that is the same as it wich makes sense scince $\operatorname{^{\mathcal{L}}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}\left[ x^{a}\right] = \operatorname{^{C}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}\left[ x^{a}\right] = \operatorname{_{0}D}\limits_{x}^{\alpha}\left[ x^{a}\right] $.