I'm reading through Aluffi's Algebra Chapter 0 and one of the exercises is to come up with a definition of an epimorphism and show that a map $f \colon A \to B$ is surjective iff it is an epimorphism.

In hindsight it's obvious to say that (Definition 1) $f$ is an epimorphism if for all maps $g_1, g_2 \colon B \to Z$, if $g_1 \circ f = g_2 \circ f$, then $g_1 = g_2$ (right-cancellation).

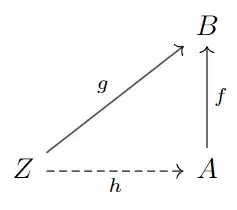

However, when I first approached the problem I had something about existence in mind and I came up with the following diagram:

Here, I wanted to define an epimorphism as follows: (Definition 2) $f$ is an epimorphism if for all maps $g \colon Z \to B$, there exists a map $h \colon Z \to A$ such that $g = f \circ h$.

In that case, a proof would go as follows (I will assume all sets $A,B,Z$ are nonempty):

Suppose $f$ is surjective. Then, for all $b \in B$, the preimage $f^{-1}(\{b\})$ is nonempty, so we can pick an element $a_b \in A$ such that $a_b \overset{f}{\mapsto} b$. Now if $z \overset{g}{\mapsto} b$ for $z \in Z$, then we can let $h(z)=a_b$. We can repeat this exercise for any $b' \in B$ that is mapped to under $g$.

On the other hand, suppose $f$ is an epimorphism according to Definition 2. Choose an element $b \in B$ and let $g$ be the constant map $g(z) \equiv b$. Then there exists a map $h \colon Z \to A$ such that $f(h(z))=g(z)=b$, so there is some $a \in A$ mapping to $b \in B$ under $f$. Again we can repeat this for any $b' \in B$.

Question 1 Is my proof correct and the definition sound?

Question 2 If the answer to Q1 is yes, then I assume I didn't just invent some new property in category theory but rather that this is some property that possibly has a name. (Would it qualify as a universal property?)