(I assume you're familiar with the unit-circle definitions of $\sin$ and $\cos$ and also some trigonometric identities.)

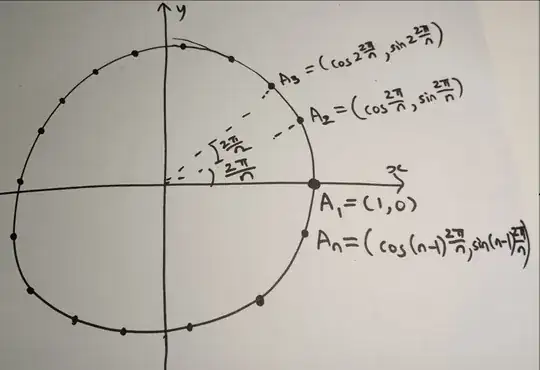

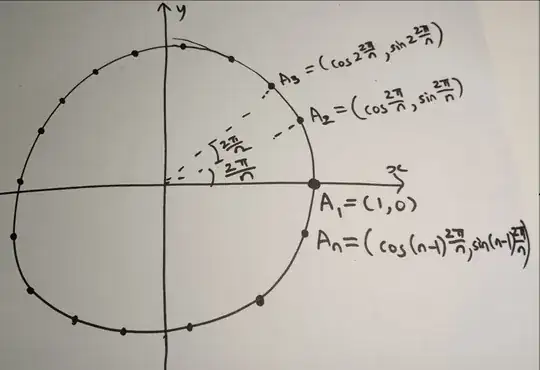

Let $O=\left(0,0\right)$, $A_{1}=\left(1,0\right)$, $A_{2}=\left(\cos\frac{2\pi}{n},\sin\frac{2\pi}{n}\right)$, $A_{3}=\left(\cos2\frac{2\pi}{n},\sin2\frac{2\pi}{n}\right)$, $\dots$, and $A_{n}=\left(\cos\left(n-1\right)\frac{2\pi}{n},\sin\left(n-1\right)\frac{2\pi}{n}\right)$.

Observe $A_{1}$, $A_{2}$, $\dots$, and $A_{n}$ are the vertices of the regular $n$-sided polygon centered on $O$.

Let $\mathbf{S}=\overrightarrow{OA_{1}}+\overrightarrow{OA_{2}}+\dots+\overrightarrow{OA_{n}}=\left(S_{x},S_{y}\right)$.

Then $S_{x}=1+\cos\frac{2\pi}{n}+\cos2\frac{2\pi}{n}+\dots+\cos\left(n-1\right)\frac{2\pi}{n}$.

And, $S_{y}=0+\sin\frac{2\pi}{n}+\sin2\frac{2\pi}{n}+\dots+\sin\left(n-1\right)\frac{2\pi}{n}$.

It can be shown that $S_{x}=0$ (see here—I recommend Sasha's answer which uses only the Product-to-Sum Identity for Sine and Cosine).

It can be shown that $S_{y}=0$ (see here—I recommend user65203's answer).

Altogether, $\mathbf{S}=\left(0,0\right)$.