How can I find nicely behaving functions which are easy to compute and which fit well to the upper limits of the (2-logarithm) of the nCr function?

What I am interested in in practice is to be able to model "how many binary digits (bits) will a digital representation of nCr(a,b)" have? A guess of 1 or 2 too many bits are acceptable, but a guess of 1 or 2 too few bits are not. So the problem is a bit un-symmetric. Errors in one direction are catastrophically problematic (unable to represent the number) but errors in the other direction "only" cause an unnecessary extra percentage of bits stored.

Actually calculating factorials will not be considered easy enough. On the other hand, the simplest of approximations like $nCr(a,b) \leq 2^a$ will be considered too sloppy.

Own work what I have tried on my own is to calculate the number of bits of all numbers, then fit low order polynomials to the bit count, then rounded the estimation to closest integer. In the case of too few bits I have updated the constant term by as much as to give a 0.01 margin that every number gets rounded right.

If I do this, I will for

- 2:nd degree polynomial get 2.82 % unnecessary bits.

- 3:rd degree polynomial get 1.96% unnecessary bits.

- 4:th degree polynomial get 1.423% unnecessary bits.

- 5:th degree polynomial get 1.1356%

- 6:th degree polynomial get 0.9258%

- 7:th degree polynomial get 0.7823%

For higher order polynomials it seems I get numerical issues. Perhaps I need to apply regularization or come up with a smarter way than just adjusting the constant term when too few bits are predicted.

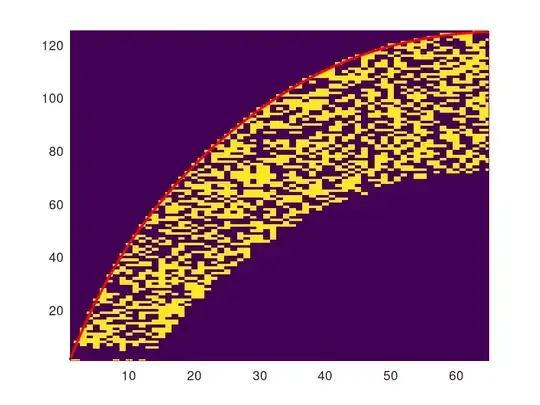

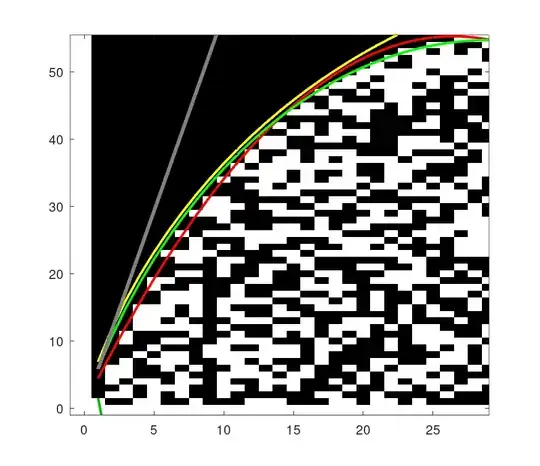

Here is a visualization of what I am trying to do. Y axis is the number $a$ as a binary number. Yellow means set bit (digit 1), blue means unset bit (digit 0). The red curve is the model. It is fit with regression using a polynomial model against the uppermost yellow a for every b. It should roughly be the same as a polynomial fit against 2-logarithm of $nCr(a,b)$.

The goal is to as closely as possible capture how many bits are required for each value of nCr.

Edit the lower portions of zeroes in the graph seem to be a numerical error due to me using floating point arithmetics and poor choice of calculations.

Update

For practical reasons I have for now settled for using the rather crude estimation $nCr(a,b) \leq 2^a$ capped to octets, i.e. $8\cdot \lceil a/8 \rceil$ bits assigned to every such number. It still helps shrink the required memory quite a bit.

Storing $0\leq a \leq 2048$ took over 1GB using a naiive table not utilizing triangular structure and symmetry - simply storing 2048 bits for every single number. With some smarter book-keeping I got it down to ~260 MB and with the mentioned octet-capping down to ~180 MB. It is sure that more memory can be saved by using for example LeonBloys estimate. But the computational costs in keeping track where all the bits are and to compress and extract them using bit-manipulation will probably affect performance too much. At least for my current applications.