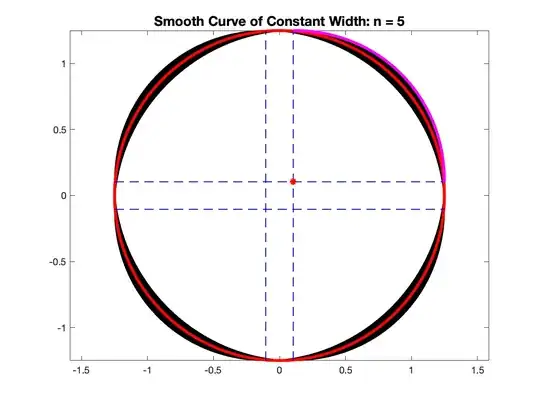

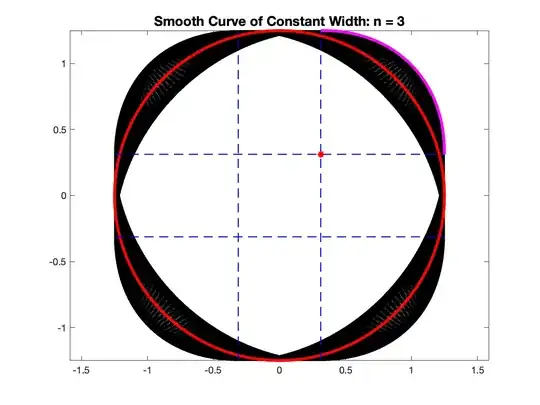

Given the functions $$ p(θ) = \frac{S}{2} × \frac{\cos\bigl(n × (θ - α)\bigr)}{n^2 - 1}\\ \begin{align} X(θ) = \cos(θ) × &\left(p(θ) + \frac{S}{2} + A\right) - \sin(θ) × p'(θ) - p(0)\\ Y(θ) = \sin(θ) × &\left(p(θ) + \frac{S}{2} + A\right) + \cos(θ) × p'(θ) - p\left(\frac{π}{2}\right) \end{align} $$ the curve $\bigl(X(t), Y(t)\bigr), 0° ≤ t < 360°$ is a smooth, regular $n$-sided polygonal Curve of Constant Width (CoCW) where

- $p'(θ)$ is the derivative of $p(θ)$ with respect to $θ$,

- $A > 0$ is the radius of the smallest osculating circle on the curve,

- $S + A > 0$ is the radius of the largest osculating circle on the curve,

- $S + 2 A$ is the total width of the curve, and

- $α$ is an angle parameter that rotates the curve about the origin.

- (If $A = 0$, the curve has sharp corners at the "vertices" and thus loses the property of being everywhere-smooth, but everything else holds. If $S = 0$, the curve becomes a circle with radius $A$.)

We also define $N := n - \sin\left(\frac{π}{2} × n\right)$.

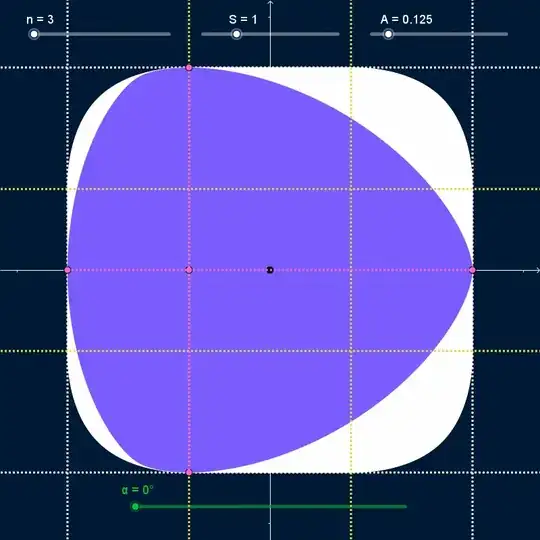

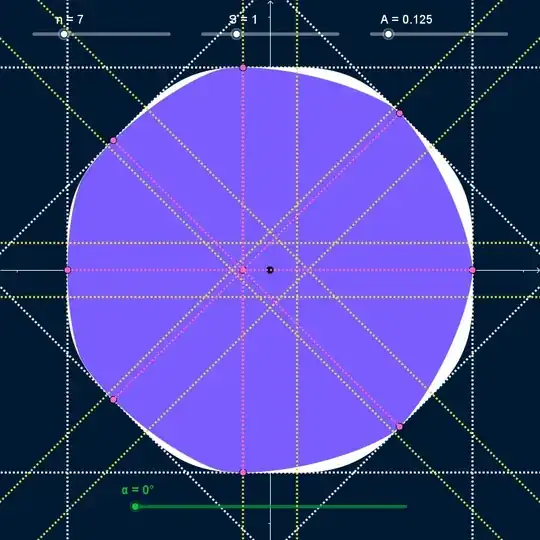

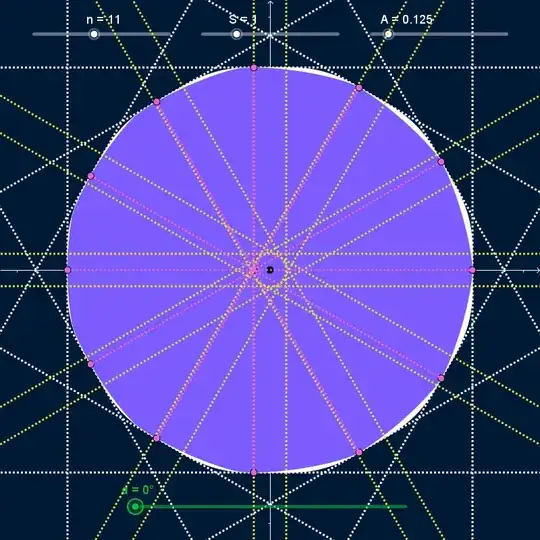

As $α$ varies and the curve rotates, it stays bounded inside a regular polygon with $N$ sides centered on the origin with width and height equal to $S + 2 A$ (dashed white lines in the GIFs below). At all times, the curve touches every side of the bounding polygon at exactly one point (pink points in the GIFs below). However, the rotating curve doesn't completely cover the square; the covered area (solid white in the GIFs below) has rounded corners. I want to find the precise shape of those corners.

The bounding-box isn't completely rounded. It has a straight line-segment as the center of all four sides, with length $\frac{S × N}{n^2 - 1}$ (bounded by yellow lines in the GIFs above). However, I'm not sure how to find mathematical descriptions of the curves that join those straight segments together.

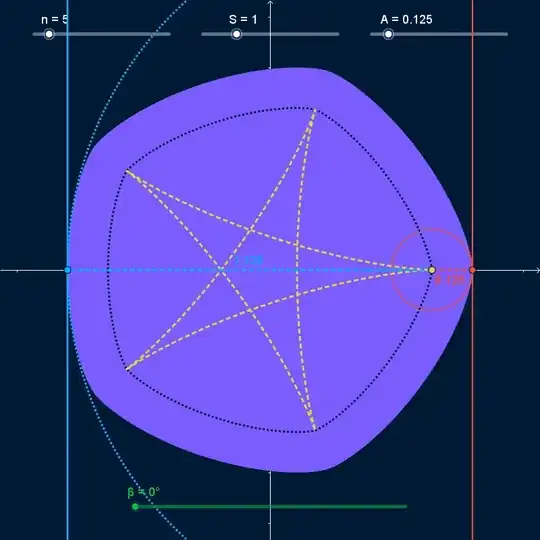

A Note on Osculating Circles

Given a point on a curve, an osculating circle shares a tangent with the curve at that point and has curvature (inverse of radius) equal to the curvature of the curve at that point. With the CoCW in this question being defined by the functions $X(t)$, $Y(t)$, we can draw two points on the curve $P_{1} = \bigl(X(β), Y(β)\bigr)$ and $P_{2} = \bigl(X(β + π), Y(β + π)\bigr)$. Because we are dealing with a CoCW, the tangents of the curve at these two points are parallel for any $β$ and the center-points of the osculating circles at both points are the same, located at $P_{0} = \bigl(X(β) - Y'(β), Y(β) + X'(β)\bigr)$. As we let $β$ vary, the smallest radius of the osculating circles on this curve will be $A$, and the largest radius will be $S + A$.