let $a,b,c>0$,and such $a+b+c=3$,

show that $$\dfrac{2}{(a+b)(4-ab)}+\dfrac{2}{(b+c)(4-bc)}+\dfrac{2}{(a+c)(4-ac)}\ge 1$$

I think this inequality use this $$ab\le\dfrac{(a+b)^2}{4}$$

let $a,b,c>0$,and such $a+b+c=3$,

show that $$\dfrac{2}{(a+b)(4-ab)}+\dfrac{2}{(b+c)(4-bc)}+\dfrac{2}{(a+c)(4-ac)}\ge 1$$

I think this inequality use this $$ab\le\dfrac{(a+b)^2}{4}$$

Step 1. Transformation.

The three dimensional problem can be re-formulated as a two dimensional problem by introducing, quite like here ,

exactly the same triangle coordinates:

$$

\left[ \begin{array}{c} a \\ b \\ c \end{array} \right] =

\left[ \begin{array}{c} 3 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] +

\left[ \begin{array}{c} -3 \\ 3 \\ 0 \end{array} \right] x +

\left[ \begin{array}{c} -3 \\ 0 \\ 3 \end{array} \right] y

$$

Then the inequality $\;\frac{2}{(a+b)(4-ab)}+\frac{2}{(b+c)(4-bc)}+\frac{2}{(a+c)(4-ac)}\ge 1\;$ does not so much "simplify", but anyway becomes an inequality in two

variables. And the equation $\;a + b + c = 3\;$ corresponds with a normed 2-D triangle, with vertices $(0,0),(1,0),(0,1)$ .

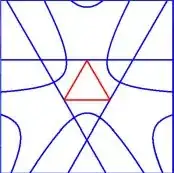

Step 2. Visualization.

The insides and outsides of both can easily be visualized, as has been done in the above picture on the right (seen in the plane of the triangle, with a transformation rectangular $(x,y) \rightarrow$ equilateral) :

$\color{red}{red}$ for

the edges of $\;a + b + c = 3\;$ and $\color{green}{green}$ for $\;\frac{2}{(a+b)(4-ab)}+\frac{2}{(b+c)(4-bc)}+\frac{2}{(a+c)(4-ac)} < 1\;$ and simply white for $\;\frac{2}{(a+b)(4-ab)}+\frac{2}{(b+c)(4-bc)}+\frac{2}{(a+c)(4-ac)} > 1\;$ .

(With a smooth function - this one is not - the isolines would look a lot "neater".)

It is seen in the same picture that the vertices of the triangle could well have been put on the curve $\frac{2}{(a+b)(4-ab)}+\frac{2}{(b+c)(4-bc)}+\frac{2}{(a+c)(4-ac)} = 1$ . However, this would require that $x=0$ and/or $y=0$ , which is excluded by $\;b=3x,c=3y$ both $> 0$ . For the rest the triangle is seen to be on the outside of that curve , i.e. in the white area, thus establishing, at first sight, the given inequality.

Step 3. Triangle edges.

Due to the denominators which can be zero, singularities - $\color{blue}{blue}$ lines in the middle picture - are an issue with this problem. It is seen that the vertices of the triangle are located at singular spots. Without the additional requirement $a,b,c > 0$ that would have been problematic.

Indeed. Define the function:

$$

f(a,b,c) = \frac{2}{(a+b)(4-ab)}+\frac{2}{(b+c)(4-bc)}+\frac{2}{(a+c)(4-ac)}

$$

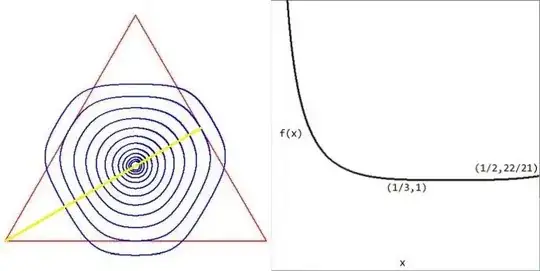

And specify for the triangle coordinates along one of the edges, say $c=3y=0$ , then:

$$

f(a=3-3x,b=3x,c=0) = \frac{2}{3[4-9(1-x)x]} + \frac{2}{12x} + \frac{2}{12(1-x)} \\ = \frac{2/27}{(x-1/2)^2+7/36} + \frac{1/6}{1/4-(x-1/2)^2}

$$

As expected, singularities are found for $x=0,1$ . The minimum function value along a triangle edge equals $22/21 > 1$ and is found for $x=1/2$ . To be certain, by differentiation we find:

$$

f'(x) = -\frac{2(2x-1)}{27\left[(x-1/2)^2+7/36\right]^2} + \frac{2x-1}{6\left[1/4-(x-1/2)^2\right]^2} = 0

$$

From which it is immediately clear that $x=1/2\;$ is a solution. And in the neighborhood $x\approx 1/2$ : $f'(x) \approx (-2/27(36/7)^2+4^2/6)(2x-1) = 104/147(2x-1)$ which is $< 0$ for $x < 1/2$ and $> 0$ for $x > 1/2$ , hence a minimum.

Step 4. Triangle inside.

There is not a whole bunch of points inside the triangle where $f(a,b,c) = 1$,

because otherwise we would have seen them as green pixels. But the fact that

they are not seen is not a proof that they do not exist. So we still have to

establish, analytically, that $f(a,b,c)$ assumes no smaller values than $1$ inside the triangle.

Luck is on our path. In one of the comments accompanying the question

Why does Group Theory not come in here? a key reference is mentioned:

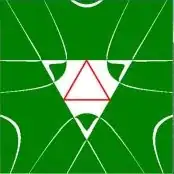

Update. As a reply to the comments about whether there could perhaps exist

a minimum at a lower level than $1$ , here comes a contour plot of $\;f(a,b,c)\;$

values in the plane of the triangle at levels $\; 1 < (2^k*10+2)/(2^k*10+1) \quad , \quad k=0 , \cdots , 11$ .

Showing a rather "flat" function behaviour, though definitely descending

towards the middle of the triangle : the perimeters of the contours are invariably diminishing with increasing values of $\;k\;$.

Let's specify $f(a,b,c)$ for $y=x\;$ i.e. $\;a=3(1-2x) , b=3x , c=3x$ . This is the yellow line in the contour plot on the left. Then we have: $$ f(x) := f(3(1-2x),3x,3x) = \frac{4}{3(1-x)(4-9x+18x^2)}+\frac{1}{3x(4-9x^2)} $$ The graph of this function is seen on the right. As expected, there is a positive singularity at $x=0$ . Then the function decreases uniformly until it reaches its minimum $f(1/3)=1$ at the center of the triangle. After that it raises a little bit until that local maximum $f(1/2)=22/21$ in the middle of an edge. That $f(1/3)=1$ is indeed a minimum can be verified by calculating $f'(1/3) = 0$ .

Here is a “brute-force” proof. Let us denote your sum by $S$. We may assume without loss that $a$ is smaller than both $b$ and $c$ ; then $a\leq 1$. Let us put $s=b+c=3-a,t=b-c$.

Lemma There are numbers $M,a_0,a_1,a_2,a_3,b_1,b_2,b_3$ that can be written as polynomials in $a$, such that $b_1,b_2,b_3$ are all nonnegative, $M$ is positive, $a_0=\frac{4M}{(6-s)(s^2-3s+8)},a_2=\frac{M}{2s(16-s^2)^2}$, and the identity $M-(4-ab)(a+b)(a_0+a_1t+a_2t^2+a_3t^3)=ct^2(b_1+b_2c+b_3c^2)$ holds.

The (ugly) proof of this lemma is deferred to the end of this answer. Noticing that when $b$ and $c$ are interchanged, $t$ becomes $-t$, and noticing also the identity $(16-s^2)^2-4(4-bc)(16-s^2-(b-c)^2)=(b-c)^4$ (remember that $s=b+c$), we see that

$$ \begin{array}{lcl} \frac{1}{(a+b)(4-ab)} &\geq& \frac{a_0+a_1t+a_2t^2+a_3t^3}{M} \\ \frac{1}{(a+c)(4-ac)} &\geq& \frac{a_0-a_1t+a_2t^2-a_3t^3}{M} \\ \frac{1}{(b+c)(4-bc)} &\geq& \frac{4}{s(16-s^2)}-\frac{4}{s(16-s^2)^2}t^2 \ \\ \end{array} $$

Adding up and multiplying by $2$, we see that

$$ S \geq \big(\frac{4a_0}{M}+\frac{8}{s(16-s^2)}\big)+ \big(\frac{4a_2}{M}-\frac{8}{s(16-s^2)^2}\big)t^2= \frac{8}{(6-s)(s^2-3s+8)}+\frac{8}{s(16-s^2)} $$

We are then done by noticing that $s\in[2,3]$ and that the RHS of this inequality can be rewritten as

$$ 1+\frac{4+(s-2)^2(2(3-s)+8)+(s-2)^3\big(\frac{3-s}{2}\big)}{s(6-s)(16-s^2)(s^2-3s+8)} $$

Equality is reached iff $a=b=c=1$.

Proof of lemma Take

$$ \begin{array}{lcl} M &=& 3(((a-7)(a^2-9)(a+1))^2)(a^2-3a+4)((a^2-3a+8)^2) \\ a_1 &=& 24(((a-7)(a-3)(a+1))^2)(3a-4)(a^2-3a+4) \\ a_3 &=& (1-a)(a^8 - 14a^7 + 177a^6 - 1152a^5 + 3903a^4 - 1362a^3 - 10033a^2 + 5984a - 4416) \\ b_1 &=& (((1-a)^{10} + 26(1-a)^9 + 213(1-a)^8 + 1572(1-a)^7 + 7256(1-a)^6 + 18720(1-a)^5)a^2 + (19696(1-a)^5 + 91664(1-a)^4 + 58944(1-a)^3 + 23040(1-a)^2 + 6912(1-a))a + 6912(1-a)) \\ b_2 &=& 3a^{11} - 66a^{10} + 842a^9 - 7038a^8 + 36340a^7 - 100374a^6 + 89838a^5 + 134190a^4 - 316271a^3 + 249000a^2 - 107968a + 35328 \\ b_3 &=& a(1-a)( -2a^8 + 28a^7 - 354a^6 + 2304a^5 - 7806a^4 + 2724a^3 + 20066a^2 - 11968a + 8832) \\ \end{array} $$

By C-S $$\sum_{cyc}\frac{1}{(a+b)(4-ab)}=\sum_{cyc}\frac{(c+6)^2}{(a+b)(4-ab)(c+6)^2}\geq$$ $$\geq\frac{\left(\sum\limits_{cyc}(c+6)\right)^2}{\sum\limits_{cyc}(a+b)(4-ab)(c+6)^2}=\frac{441}{\sum\limits_{cyc}(a+b)(4-ab)(c+6)^2}.$$ Thus, it remains to prove that $$882\geq\sum\limits_{cyc}(a+b)(4-ab)(c+6)^2.$$ Let $a+b+c=3u$, $ab+ac+bc=3v^2$ and $abc=w^3$.

Hence, it's obvious that the last inequality is a linear inequality of $w^3$,

which says that it's enough to prove the last inequality for the extremal value of $w^3$,

which happens in te following cases.

Let $c\rightarrow0^+$ and $b=3-a$.

After this substitution we obtain: $$882-\sum\limits_{cyc}(a+b)(4-ab)(c+6)^2=18>0;$$

In this case we get $(a-1)^2(2a^3-3a^2+6a+3)\geq0$, which is obvious.

Done!

It is possible to prove a slightly weaker bound by cutting down the dimension of the problem.

For any $K\in[0,3]$, define: $$f_K(x)=\frac{2}{(3-x)(4-x(K-x))},\qquad g_K(x)=f_{K}(x)+f_{K}(K-x).$$ By differentiating with respect to $x$, we have that the minima of $g_K(x)$ over $[0,3]$ are located in $\frac{K}{2}\pm\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{1+(3-K)^2}$, so $$g_K(x) \geq g_K\left(\frac{K}{2}\pm\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{1+(3-K)^2}\right)=\frac{8(6-K)}{(13-3K)^2}$$ holds over $[0,K]$. By taking $x=b,K=b+c$, $a=3-K$ follows and we have: $$\sum_{cyc}\frac{2}{(3-a)(4-bc)}=\frac{2}{K(4-x(K-x))}+g_K(x).\tag{1}$$ The first term in the RHS is a non-negative and convex function $h_K(x)$ on $[0,K]$ whose graphics is symmetric with respect to $x=K/2$. Since $h_K(K/2)>h_K(0)$, $h_K(x)\geq h_K(0)=\frac{1}{2K}$ follows. This gives: $$\sum_{cyc}\frac{2}{(3-a)(4-bc)}\geq\frac{1}{2K}+\frac{8(6-K)}{(13-3K)^2}=j(K).\tag{2}$$ $j(K)$ is a convex function over $[0,3]$, whose minimum is attained in $x=1.4638\ldots$. This gives:

$$\sum_{cyc}\frac{1}{(3-a)(4-bc)}\geq 0.831262\ldots > \frac{4}{5}.\tag{3}$$ We can improve this to: $$\sum_{cyc}\frac{1}{(3-a)(4-bc)}\geq h_K\left(\frac{K}{2}-\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{1+(3-K)^2}\right)+\frac{8(6-K)}{(13-3K)^2}=\frac{4(13+9K-2K^2)}{K(13-3K)^2},\tag{4}$$ where the RHS is increasing on $[2,3]$. Since we can assume $K=(b+c)\geq 2$ without loss of generality, we have: $$\sum_{cyc}\frac{1}{(3-a)(4-bc)}\geq\frac{46}{49}.\tag{5}$$

Remarks: By the way, by AM-GM, we have $$\mathrm{LHS} \ge 3\sqrt[3]{\frac{2}{(a+b)(4-ab)}\cdot \frac{2}{(b+c)(4-bc)}\cdot\frac{2}{(a+c)(4-ac)}}. $$ It suffices to prove that $$216 \ge (a + b)(b + c)(c + a)(4 - ab)(4 - bc)(4 - ca). $$ This is true. However, I don't have a nice proof.

Supplement to Michael Rozenberg's very nice answer

According to Michael Rozenberg's result, it suffices to prove that $$882\geq\sum\limits_{cyc}(a+b)(4-ab)(c+6)^2.\tag{1}$$

We use pqr method instead.

Let $p = a + b + c = 3, q = ab + bc + ca, r = abc$.

(1) is written as $$2qr-24r+18 \ge 0.$$

Using $q^2 \ge 3pr$, it suffices to prove that $$2r \cdot \sqrt{9r} - 24r + 18 \ge 0$$ or $$6(1 - \sqrt r)(3 + 3\sqrt r - r) \ge 0$$ which is true since $0 \le r \le 1$ (by AM-GM, $r \le (p/3)^3 = 1$).

We are done.

$\frac{3}{\dfrac{1}{(a+b)(4-ab)}+\dfrac{1}{(b+c)(4-bc)}+\dfrac{1}{(a+c)(4-ac)}} \leq \frac{(a+b)(4-ab)+(a+c)(4-ac)+(b+c)(4-bc)}{3}=(*)$

using $a+b+c=3$, $a+b=3-c$,$a+c=3-b$ and $c+b=3-a$ we have:

$()=\frac{(3-c)(4-ab)+(3-b)(4-ac)+(3-a)(4-bc)}{3}=\frac{36-3(ab+ac+bc)-4(a+b+c)+3abc}{3}=(*)$

Using $a+b+c=3$:

$(**)=\frac{24-3(ab+ac+bc)+3abc}{3} \leq \frac{24+3}{3}=9$

which gives $2/3$ instead of $1$ on the right side of the inequality, so, it's sort of close... maybe soneone can inprove that (or use HM-GM instead of HM-AM).

– user119459 Jan 08 '14 at 15:14