A sharp answer to your question

Theorem: A domains $\Omega\subset \Bbb R^d$ satisfies the both interior and exterior sphere condition if and only if $\partial \Omega$ is $C^{1,1}$. See Theorem 1.0.9, here

Counter-example of $C^{1,\alpha}$ domain not satisfying the interior sphere condition

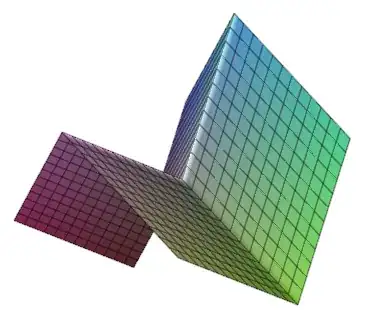

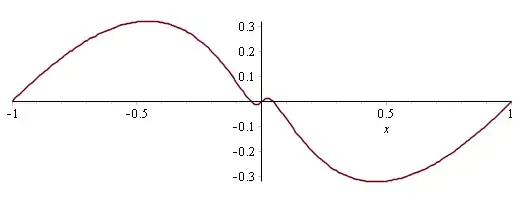

Consider $\Omega=\{(,)\in \Bbb R^2:>||^{1+\alpha}\},$ with $0\leq \alpha<1$. This domain is $C^{1,\alpha}$ smooth. Because for $ f(x)= |x|^{1+\alpha},$ we have $f'(x)=(\alpha+1) |x|^{\alpha-1}x$ which is $\alpha$-H"older continuous. In fact it can be shown that

\begin{align}

|f'(x)- f'(y)|= \alpha||x|^{\alpha-1}x-|y|^{\alpha-1}y|\leq (\alpha+1)2^{1-\alpha} |x-y|^{\alpha}\,.

\end{align}

Let $ B= B((x_0, y_0), r)$ , $r>0$ be a ball touching the boundary at $(0,0)$ and such that $ \overline{B}\subset \Omega$. We have that $(0,0)\in \partial \Omega\cap B((x_0, y_0), r)$ then necessarily

\begin{align*}

\text{$x_0^2 +y_0^2=r^2$ and $y_0>|x_0|^{1+\alpha}$}\implies y_0= \sqrt{r^2-x_0}.

\end{align*}

Moreover, since $\partial B\subset \Omega$ in particular the bottom part $\partial B_-= \{ (x,y): y=y_0- \sqrt{r^2-(x-x_0)^2} \}$ is contained in $\Omega$. That is, for all $(x,y)\in \partial B_-$

with $|x-x_0|\leq r$ we have

\begin{align*}

y=y_0- \sqrt{r^2-(x-x_0)^2}= \sqrt{r^2-x_0}- \sqrt{r^2-(x-x_0)^2}\qquad\text{and}\qquad y>|x|^{1+\alpha}

\end{align*}

That is for all $|x-x_0|\leq r$ we get that

\begin{align*}

\sqrt{r^2-x_0^2}- \sqrt{r^2-(x-x_0)^2}>|x|^{1+\alpha}

\end{align*}

Letting $x\to x_0$ it follows that

\begin{align*}

r^2-x_0^2\geq (r+|x_0|^{1+\alpha})^2\Longleftrightarrow -x_0^2\geq 2r|x_0|^{1+\alpha}+|x_0|^{2(1+\alpha)}

\end{align*}

Which is possible only if $x_0=0$ so that $y_0=r$ that is $(x_0, y_0)= (0,r)$. In this case, for $0<|x|<r$, the above inequality becomes

\begin{align*}

r^2+|x|^{2(1+\alpha)} -2r|x|^{1+\alpha}= (r-|x|^{1+\alpha})^2> r^2-x^2, \quad \text{ i.e., }\quad |x|^{2\alpha} -2r|x|^{\alpha-1}+1)>0.

\end{align*}

Given that $ |x|^{2\alpha} -2r|x|^{\alpha-1}+1\xrightarrow{x\to0}-\infty$ as $\alpha-1<0$, there is $0<|x|<r$ such that

\begin{align*}

-1>( |x|^{2\alpha} -2r|x|^{\alpha-1}+1)>0.

\end{align*}

This is impossible and hence the point $(0,0)$ does not satisfies the interior sphere condition. However $(0,0)$ satisfies the exterior sphere condition.