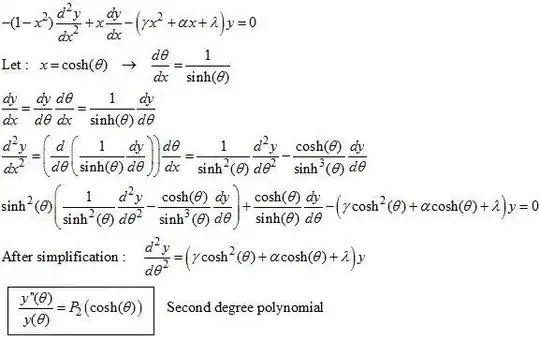

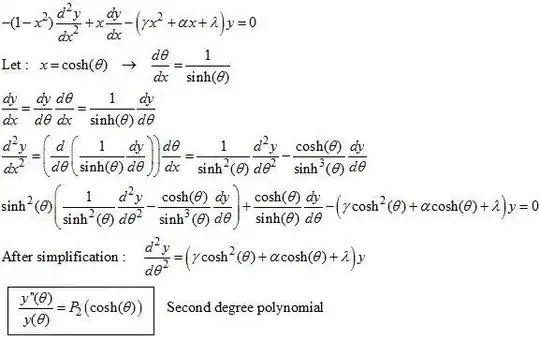

With convenient change of variable, the ODE can be transformed to another ODE on a simplified form : $\frac{y’’(t)}{y(t)}=P_2(\cosh(t))$ where $P_2$ is a polynomial of the second degree.

It is known that some particular ODE’s of this form can be solved in terms of MathieuS and MathieuC functions: http://mathworld.wolfram.com/MathieuDifferentialEquation.html

For example, this is the case if one of the coefficient is null and the two others not null : in the case $\gamma=0$ or in the case $\alpha=0$. But not in the case $\lambda=0$. Other cases are solvable in case of particular relationship between the coefficients, in terms of Mathieu funcions or in terms of other special functions of lower level for particular values of the coefficients of the polynomial.

In the general case, i.e. $\alpha, \gamma, \lambda$ not null and not related one to another, a closed form for the solutions would certainly require special functions of higher level, which are not referenced as standard functions. So, I think that the ODE on its general form cannot be analytically solved in that sense.

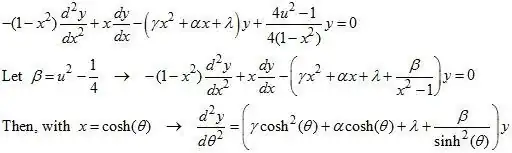

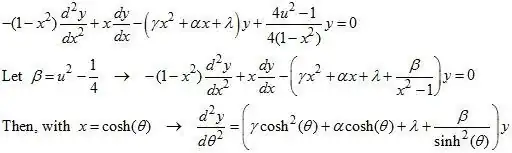

The second EDO with one more term becomes on the reduced form :

A fortiori, in the general case, the solutions cannot be expressed with a finite number of standard functions. But closed forms of solutions could exist in some cases of particular values of the coefficients $\alpha, \gamma, \lambda, \beta$

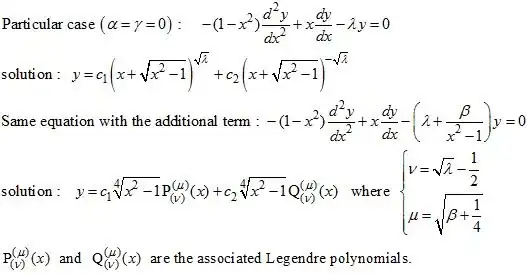

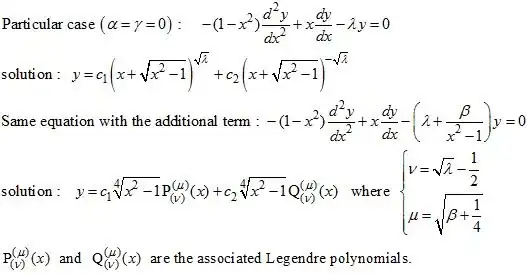

Adding a term of different nature to an ODE generally changes a lot the form of the solution. A simplified example is shown below : The solution of the ODE which was expressed in terms of elementary functions becomes much more complicated because requiring special functions (associated Legendre) :

Another example which involves even more complicated functions :

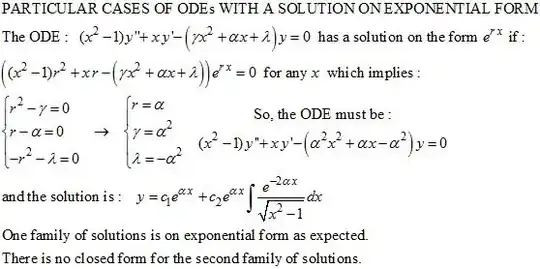

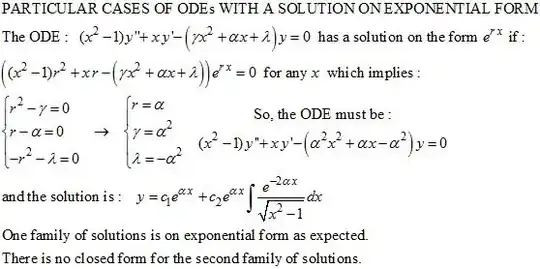

A solution on the exponential form exists in case of particular relationships between the parameters $\gamma, \alpha, \lambda$ :

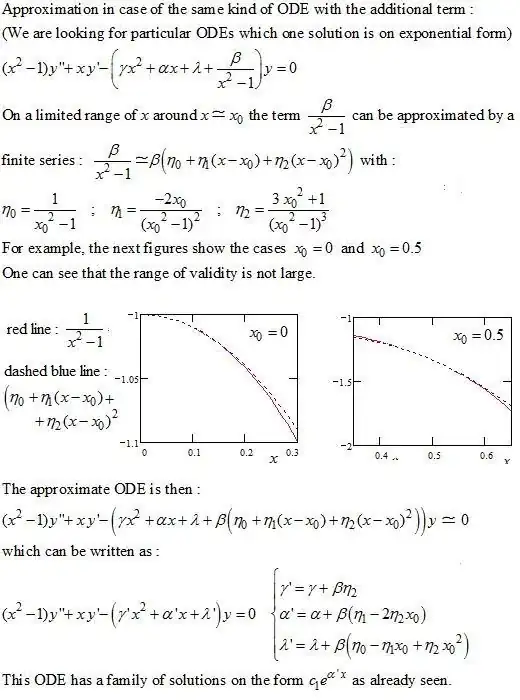

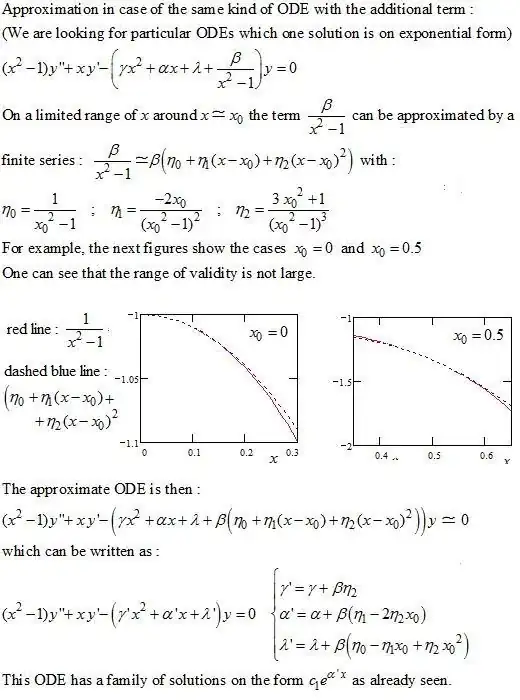

With the additional term, an approximative solution on exponential form can also be found in case of particular relationships between the parameters $\gamma, \alpha, \lambda, \beta$ :

But this is of low interest for practical application because it cannot be generalized to ODEs which parameters are not related on the same way.

All this draw to think that the analytic method is not convenient to tackel this problem in case of a so complicated ODE. Other approaches might be more convenient, especially systematic studies with numerical methods.