All sub cases. Consider the strip embedded inside the square, as mentioned in the question, a bit modified though

(without loss of generality):

$$

\left|\, \cos(\phi) x + \sin(\phi) y\, \right| < c \quad

\mbox{with} \; c > 0 \; , \; 0 \le \phi < \pi

\quad \mbox{for} \; 0 \le x \le 1 \; , \; 0 \le y \le 1

$$

The vertices of the square are $\;(x_k,y_k) = \left\{(0,0),(1,0),(0,1),(1,1)\right\} , \; k=0,1,2,3\;$ .

Each of the vertices can be, in principle

- $(0)$ below the strip: $\;\cos(\phi) x_k + \sin(\phi) y_k \le -c$

- $(1)$ inside the strip: $\;-c < \cos(\phi) x_k + \sin(\phi) y_k < +c$

- $(2)$ above the strip: $\;+c \le \cos(\phi) x_k + \sin(\phi) y_k$

With exception of $(x_0,y_0) = (0,0)$ ; this vertex is always inside the strip. (You're lucky, otherwise you had to distinguish $3^4 = 81$ cases to begin with.)

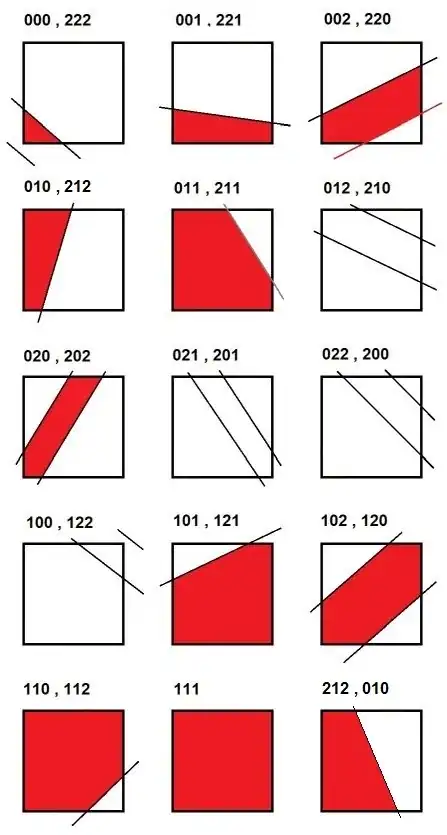

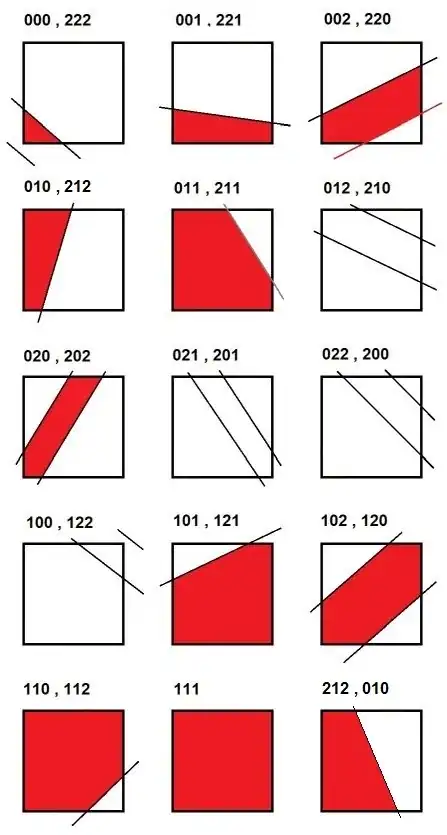

Now there are $3^3 = 27$ sub cases, in principle. They can be conveniently enumerated in a

base $3$ number system . For example $210$ means that vertex $(1,0)$ is below the strip, vertex $(0,1)$ is inside the strip and vertex $(1,1)$ is above the strip: the number is read from the right to the left, i.e. towards the most significant digit (as usual). Because of the restriction $0 \le \phi < \pi$ only the cases $\;000 \cdots 111\;$ have

to be considered. The other cases are a mirror of these if $0 \le \phi < 2\pi$ is allowed eventually. With

one noteworthy exception, though, namely $010 \not \equiv 212$ ($\color{red}{red}$) . So here comes:

$$

\begin{matrix}

000 & 001 & 002 & \color{red}{010} & 011 & 012 & 020 & 021 & 022 & 100 & 101 & 102 & 110 & 111 \\

222 & 221 & 220 & \color{red}{212} & 211 & 210 & 202 & 201 & 200 & 122 & 121 & 120 & 112 & \\

& & & & & NOP & & NOP & NOP & NOP & & & &

\end{matrix}

$$

A picture says more than a thousand words:

It is seen that there are at most

11 sub cases that must be taken into account.

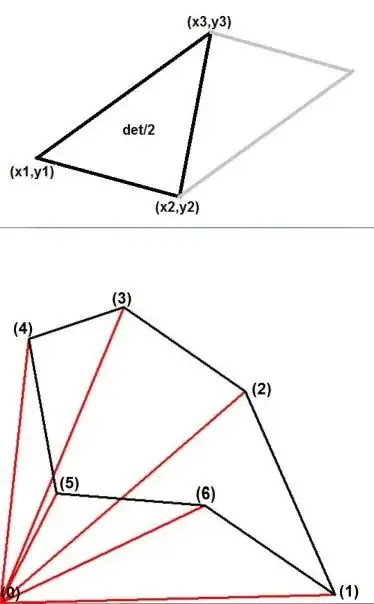

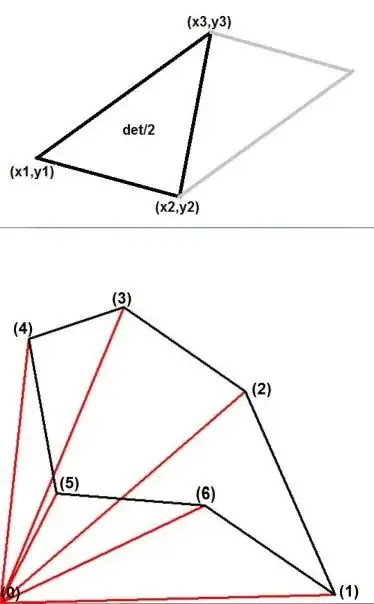

Area of polygon. Though at the moment we have only an impression of what

the polygons look like, the areas of them have to be calculated, in the end.

So it's useful anyway to have a general method for doing just that. What we can do

is to draw ($\color{red}{red}$) lines from the origin $(0)$ to the vertices of

the polygon (six in our case) and sum up the areas of the (six) triangles $(0,1,2),(0,2,3),(0,3,4),(0,4,5),(0,5,6),(0,6,1)$ : see figure

at the bottom. The figure at the top shows how the area of just one triangle is

calculated, by using a determinant:

$$

\mbox{area}\,\Delta =

\frac{1}{2} det\begin{bmatrix}(x_2-x_1) & (y_2-y_1)\\(x_3-x_1) & (y_3-y_1)\end{bmatrix}

$$

Note that, in general, the triangle areas thus calculated can be positive as well

as negative. And the latter is essential.

To be continued for the coordinates of the polygons, in anti-clockwise order.

Clipping problem.

Usually a polygon (strip) is clipped against the square. But in our case, the square is clipped against a strip.

Once the ideas are clear, the algebra involved is very elementary. Hoping that the program below is more or less self-documentary:

program Q901259;

type

point = record

x,y : double;

end;

polygon = array of point;

function Area(round : polygon) : double;

{

Area of polygon

}

var

k,L : integer;

Det,Opp : double;

p,q : point;

begin

Opp := 0;

L := Length(round);

if L > 0 then

begin

q := round[L-1];

for k := 0 to L-1 do

begin

p := q;

q := round[k];

Det := (p.xq.y - q.xp.y);

Opp := Opp + Det;

end;

end;

Area := Opp/2;

end;

function let(x,y : double) : point;

var

P : point;

begin

P.x := x; P.y := y;

let := P;

end;

function x_is_0(c,p : double) : point;

begin

x_is_0 := let(0,c/sin(p));

end;

function x_is_1(c,p : double) : point;

begin

x_is_1 := let(1,(c-cos(p))/sin(p));

end;

function y_is_0(c,p : double) : point;

begin

y_is_0 := let(c/cos(p),0);

end;

function y_is_1(c,p : double) : point;

begin

y_is_1 := let((c-sin(p))/cos(p),1);

end;

function Calculate(p,c : double) : double;

{

Calculate area of strip inside square

xcos(p) + ysin(p) = +/- c : strip

}

const

choice : array[0..26] of integer =

(0,1,2,3,4,-1,5,-1,-1,-1,6,7,8,9

,8,7,6,-1,-1,-1,5,-1,4,10,2,1,0);

var

k,number,digit : integer;

x,y : double;

poly : polygon;

begin

SetLength(poly,1);

poly[0] := let(0,0);

number := 0;

{Ternary number system }

for k := 2 downto 0 do

begin

x := (k+1) mod 2;

y := (k+1) div 2;

digit := 1;

if cos(p)*x+sin(p)*y < -c then digit := 0;

if cos(p)*x+sin(p)*y > +c then digit := 2;

number := number*3 + digit;

end;

{All sub cases }

case choice[number] of

0 :

begin

SetLength(poly,3);

poly[1] := y_is_0(+c,p);

poly[2] := x_is_0(+c,p);

end;

1 :

begin

SetLength(poly,4);

poly[1] := let(1,0);

poly[2] := x_is_1(+c,p);

poly[3] := x_is_0(+c,p);

end;

2 :

begin

SetLength(poly,5);

poly[1] := y_is_0(-c,p);

poly[2] := x_is_1(-c,p);

poly[3] := x_is_1(+c,p);

poly[4] := x_is_0(+c,p);

end;

3 :

begin

SetLength(poly,4);

poly[1] := y_is_0(-c,p);

poly[2] := y_is_1(-c,p);

poly[3] := let(0,1);

end;

4 :

begin

SetLength(poly,5);

poly[1] := let(1,0);

poly[2] := x_is_1(+c,p);

poly[3] := y_is_1(+c,p);

poly[4] := let(0,1);

end;

5 :

begin

SetLength(poly,5);

poly[1] := y_is_0(-c,p);

poly[2] := y_is_1(-c,p);

poly[3] := y_is_1(+c,p);

poly[4] := x_is_0(+c,p);

end;

6 :

begin

SetLength(poly,5);

poly[1] := let(1,0);

poly[2] := let(1,1);

poly[3] := y_is_1(+c,p);

poly[4] := x_is_0(+c,p);

end;

7 :

begin

SetLength(poly,6);

poly[1] := y_is_0(-c,p);

poly[2] := x_is_1(-c,p);

poly[3] := let(1,1);

poly[4] := y_is_1(+c,p);

poly[5] := x_is_0(+c,p);

end;

8 :

begin

SetLength(poly,5);

poly[1] := y_is_0(-c,p);

poly[2] := x_is_1(-c,p);

poly[3] := let(1,1);

poly[4] := let(0,1);

end;

9 :

begin

SetLength(poly,4);

poly[1] := let(1,0);

poly[2] := let(1,1);

poly[3] := let(0,1);

end;

10 :

begin

SetLength(poly,4);

poly[1] := y_is_0(+c,p);

poly[2] := y_is_1(+c,p);

poly[3] := let(0,1);

end;

end;

Calculate := Area(poly);

end;

begin

Random; Random;

{ Test }

while true do

begin

Writeln(Calculate(Random*Pi,Random));

Readln;

end;

end.

But: is it possible to have a solution

without all the sub case jazz?

The answer is affirmative; that's how I actually tested the correctness of the above program.

Any area can be simply determined by

pixel counting (not necessarily in a "real" picture).

Advantage: quick and dirty. Disadvantage: less exact than the sub case method.