I believe I see that $a_n = 2^n(a_0+1) - 1$ but am somewhat uncertain where to proceed afterwards. I am a complete beginner at number theory and would appreciate it if someone could point me in the right direction--surely there is some obvious argument I am missing.

-

See here for a proof of a more general result (replace $10x+1$ by $2x+1$) – Bill Dubuque Apr 25 '20 at 00:45

3 Answers

No.

General term in your sequence is $a_n = 2^n(a+1) - 1$, where, by assumption, $a$ is prime.

There is some sufficiently large $n$ such that $2^n \equiv 1 \pmod{a}$, or in other words $2^n = k a + 1$. But then $a_n$ is divisible by $a$, hence not prime.

EDIT: As Ben Frankel rightly notes, there is a special case when $a = 2$. Argument above fails, but $a_5 = 95$ is composite, so we are in good shape regardless.

Even more general statement is true: If $p$ is a prime, $p \neq 2$, and $p$ divides one of $a_n$, then $p$ divides infinitely many $a_n$'s. In particular, if $a_n$ is an odd prime, then $a_n \mid a_m$ for infinitely many $m$, and these $a_m$'s are composite.

- 12,588

This is equivalent to find an integer $k.2^{n_0}$ such that $k$ is odd and $p_n=k.2^{n+n_0}-1$ is a prime for all $n\ge 0.$

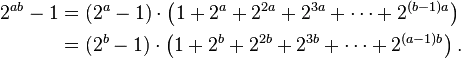

If $k=1,$ then $p_n$ is not a prime for composite $n+n_0,$ As

If $k=2m+1$ where $m\ge1,$ then we can find a large $n$ such that

$p_n=k(2^{n+n_0}-1)+(k-1)$ is not a prime.

By assumption $a_0=p$ is a prime and $a_n = 2^n(p+1)-1$.

If $p$ is an odd prime, then by Fermat's little theorem we have $2^{p-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p$, so $a_{p-1} \equiv 0 \pmod {p}$ and $a_{p-1}$ is composite (notice $a_{p-1}>p$).

Remaining case $p=2$ can be seen by simply enumerating first few values which yields $a_5=95$, a composite number.

- 16,612