For the first identity, you seem to be on the right track, but some things in your description are unclear to me and the sentence “$(i)(i!)$ 'occurs' $n$ times making it $n(n!)$” isn't correct.

As you suggest, the righthand side counts non-identity permutations of $(1,2,3,\ldots,n+1).$ So does the lefthand side: each non-identity permutation has at least one element that is not in its original position. Let $S_i$ be the set of permutations in which elements $1,2,\ldots,n-i$ are in their original positions, but element $n+1-i$ is not. There are $i$ elements that can be placed in position $n+1-i$ (any of elements $n+2-i$ through $n+1$). Then there remain $i$ elements that can be placed in any order in positions $n+2-i$ through $n+1.$ Now sum the sizes of $S_i$ for $i$ from $0$ to $n.$ Note that $S_0$ is empty and can therefore be omitted from the sum.

Added: For the second identity, I provide the following alternative to Brian Scott's proof. This proof avoids the double counting of certain outcomes and consequent need for subtraction of Brian Scott's proof, but is otherwise similar.

Say we have $n+1$ people ranked according to seniority from $0$ to $n,$ with $n$ being most senior. We are to form a committee consisting of a chair and zero or more additional members. The chair must be the most senior member of the committee. In addition, we are to choose a spokesperson who may or may not also serve on the committee, and who must be less senior than the chair. This interpretation is completely isomorphic to Brian Scott's interpretation involving colored slips of paper and a coin; I offer it only for variety and because its the one I came up with when I started thinking about the problem.

The number of ways of selecting chair, remaining committee members, and spokesperson is $\sum_{i=1}^n\,i\,2^i$ by the argument in Brian Scott's proof. We represent such a selection by a triple $(c,M,s),$ where $c$ is the chair, $M$ is the set of other committee members, and $s$ is the spokesperson. Observe that there are two selections in which the chair has rank $1$, namely $(1,\{\},0)$ and $(1,\{0\},0).$

To establish the identity, we exhibit an alternate procedure for making the selection in the case that the chair has rank $2$ or higher. The procedure is:

- choose a subset $S$ of $\{0,1,\ldots,n\};$

- choose a rank $p$ between $1$ and $n-1;$

- if $S$ contains a person of rank greater than $p,$ let $c$ be the highest ranked element of $S,$ let $M=S\setminus\{c\},$ and let $s=p;$

- if $S$ contains no person of rank greater than $p,$ let $c=p+1,$ let $M=S,$ and let $s=0.$

It is clear that this procedure always produces a valid selection, $(c,M,s)$ with $c\ge2.$ Furthermore, any valid selection, $(c,M,s),$ with $c\ge2$ is produced in a unique way by this procedure: if $s>0,$ then $(c,M,s)$ arises when $S=\{c\}\cup M$ and $p=s;$ if $s=0,$ then $(c,M,s)$ arises when $S=M$ and $p=c-1.$ It is clear that the selection can be accomplished in $(n-1)2^{n+1}$ ways.

Visual proof: I would suggest modifying

$$

\sum_{i=1}^n i\,2^i=2+(n-1)2^{n+1}

$$

by dropping the first term in the sum on the left and the term $2$ on the right. Then replace $n$ with $n+1$ to get

$$

\sum_{i=2}^{n+1} i\,2^i=n\,2^{n+2}.

$$

Divide both sides by $2^2$ and reindex the sum to obtain the equivalent identity,

$$

\sum_{i=1}^n (i+1)\,2^{i-1}=n\,2^n,

$$

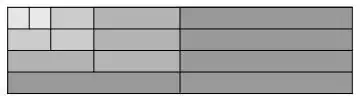

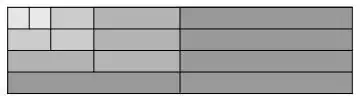

which has the visual proof shown below.

Relationship between the visual proof and the preceding bijective proof: We can see the diagram as a proof that

$$

\sum_{i=2}^5i\,2^i=4\cdot2^6.

$$

Imagine the rectangle divided into $2^6=64$ columns. So the light gray rectangle in the upper left would get divided into four columns, as would the adjacent light gray rectangle; the next, slightly darker gray rectangle would get divided into eight columns, and so on. Label columns from left to right by subsets $S\subseteq\{0,1,2,\ldots,5\}$ using the natural ordering $\{\},$ $\{0\},$ $\{1\},$ $\{0,1\},$ $\{2\},$ $\{0,2\},$ $\{1,2\},$ $\{0,1,2\},$ $\{3\},\ \ldots.$ Label rows from top to bottom by integers $p=1,2,3,4.$

So the column labels $\{\},$ $\{0\},$ $\{1\},$ $\{0,1\}$ would appear above the first light gray block, the labels $\{2\},$ $\{0,2\},$ $\{1,2\}$ above the second light gray block, the labels $\{3\},\ \ldots$, $\{0,1,2,3\}$ above the next, slightly darker gray block, and so on.

The pairs $(S,p)$ to which rule $4$ in the bijection above applies fall within the first block of each row of the diagram; the pairs to which rule $3$ applies all fall within the later blocks of each row.

Historical note: There is a visual proof by Oresme (see Victor J. Katz's A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, Third Edition, page 358) that

$$

1\cdot\frac{1}{2}+2\cdot\frac{1}{4}+3\cdot\frac{1}{8}+4\cdot\frac{1}{16}+\ldots=2,

$$

which seems similar in some respects to the visual proof above.

Some thoughts: The notion of combinatorial proof can be rather slippery. I generally interpret it to mean bijective proof, which is proof in which the two sides of an identity are interpreted as counting two sets of objects, and then those sets of objects are shown to be equinumerous by exhibiting a bijection between them, thereby establishing the identity. A special case is double-counting proof, in which a single set of objects is counted in two different ways. This is bijective proof in which the bijection is the identity.

The step in which the each side of the identity is interpreted as counting something is key. The interpretation should be natural, making use of straightforward counting principles.

I consider the proof above involving the committee to be combinatorial: the left side counts a specified set of triples $(c,M,s)$ in a straightforward way, while the right side counts a specified set of ordered pairs $(S,p)$ in an even more straightforward way. Finally, there is a bijection between the triples and the pairs.

The visual proof is also combinatorial in this sense—in some ways, it is even better. It is a double-counting proof in which the rectangle area (which consists of unit squares) is computed in two different ways—on the left by adding L-shaped regions, on the right by the trivial area formula. In another sense, however, the visual proof is not combinatorial. The exponential function $2^n$ is not given combinatorial meaning (say as the size of the power set). Only an arithmetical property is used, namely that $2^n=2^{n-1}+2^{n-1}.$