Draft - writing took longer than I thought, and I'm late for class...

I've given this question a lot of thought, and while I'm not overly convinced that my reflections are useful to a wide audience, they might be insightful to some. (At the very least, it provides me with a rationale to sit and organize my own thoughts.)

Know your pedagogy

- Learning outcomes: While there are courses intended to teach a particular programming language, I suspect more often than not, a programming language is taught within the context of another subject. That is certainly the case for me, trying to introduce Chemistry majors to the benefits of using Mathematica in their data analysis.

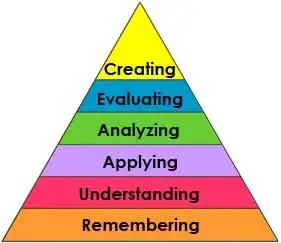

- Learning domains: Spending time "learning about learning" has helped (me) greatly in developing successful lessons. I am a fan of Bloom's Taxonomy which is a tool for categorizing educational goals (and therefore is closely associated with the previous bullet). It helps me develop a strategy for creating an effective lesson or activity by providing "bins" for the various elements of a lesson. I can look at the lesson and ask "what am I asking the students to apply?" or "am I over-emphasizing remembering of facts?"

- Understand your students' perspective: Lastly (for now) is that you should consider your students' academic history. My students have virtually no programming knowledge or experience. Naturally, there are disadvantages (how much programming do I teach in an instrumental methods class) and advantages (they have no idea what a for/while loop is, so I won't have to tell them not to use it).

From pedagogy to practice

Much of what I need students to do can be summed up in the 'motto' "Mathematica can do it better than Excel ... most of the time". An example set of learning outcomes for the statistics portion of an upper-level instrumental methods class might be

Upon completing this course, most students can

- use linear regression statistics to evaluate the quality of an instrument response in relationship to substrate concentration;

- estimate how measurement errors are propagated through to the desired result;

- utilize the student's t-test to determine whether or not the differences in two sets of measurements are statistically significant.

For the first point, I spend much time on how Excel's linest() function provides the necessary information. LinearModelFit naturally provides all of this information as well; however, I feel that students have a better chance of being exposed to Excel in the workforce than Mathematica, which adds more value to the Excel skill.

I have had more success with incorporating Mathematica into the error propagation activities. My students, sadly, have weak mathematical backgrounds and calculus is not their strong suit. Nonetheless, having a platform that allows students to perform partial differentials confidently (even if they don't - but should - know how the answer is obtained) allows me to incorporate higher-order elements of Bloom's taxonomy into my lessons (e.g. instead of remembering a separate formula for addition and multiplication of measurements with errors, they learn to apply a a single equation applicable to both situations).

Practical considerations

Perhaps the real answer to the question asked is here. Students in the chemical sciences need these Mathematica basic skills

- Import data (typically in CSV format)

- List manipulation as it pertains to filtering out nested lists and removing rows and columns that contain non-numeric information

- Plot of discrete data AND formatting of the plot to display axes labels and other information typically expected of a publication-quality plot

- Descriptive statistics, linear regression and t-test

- Occasionally, curve integration (determining peak area of an imported spectrum)

I have had success with creating CDFs and Notebooks that minimize student exposure to the underlying Wolfram Language stuff. While I feel somewhat guilty about the black-box nature of the activities (especially since I'm teaching upper level courses designed to get students thinking about what's in the black box), I fall back to the learning outcomes for my course, which at the end of the day are not programming focused.

One caveat is to make efforts NOT to turn your CDFs/notebooks into show-off eye-candy displays. We all know that Mathematica is very powerful, and with a few obfuscated lines of code one can create some pretty powerful results. The point is not to "wow" students with your skills, but to provide them with tools to develop their own skills.

The most important step

I've had the best success in incorporating Mathematica into my instruction when I have taken the time to reflect on student performance. Assessing student performance (i.e. assigning a grade) is only the first step in the reflection process. Determining whether or not the students achieved the learning outcomes, identifying the current roadblocks and revising your curriculum in response to these findings complete the process and will ultimately result in improved student performance over the long run.

Don't[]is syntactically proper. :D Less facetiously, wouldn't this have some overlap with the pitfall thread? – J. M.'s missing motivation Mar 03 '16 at 15:32Times[t[],Derivative[1][Don]]:) – rm -rf Mar 03 '16 at 15:34Do[]; loops have their place, too. – J. M.'s missing motivation Mar 03 '16 at 15:34Derivative[]? ;P – J. M.'s missing motivation Mar 03 '16 at 15:35Do[ ]. Just want it in the attic – Dr. belisarius Mar 03 '16 at 15:40init.mbefore starting to learn:Unprotect /@ {For, While}; For = While = Nothing; Protect /@ {For, While};:D – rm -rf Mar 03 '16 at 16:14