In the context of resistor networks and finding the (equivalent) resistance between two arbitrary nodes, I am trying to learn how to write a generic approach in Mathematica, generic as in an approach that also lends itself to large spatially randomly distributed graphs as well (not just lattices), where then one has to deal with sparse matrices. Before getting there, I've tried simply recreating a piece of algorithm written in Julia for solving an example on a square grid, with all resistances set to 1.

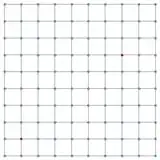

Here's the grid where each edge depicts a resistor between its incident nodes (all resistance values are assumed to be $1 \Omega$) and two arbitrary nodes ($A$ at {2,2} and $B$ at {7,8}) are highlighted, question is to find the resistance between them.

In the Julia's code snippet, the approach of injecting a current and measuring the voltages at the two nodes is adopted, as shown below: (source)

N = 10

D1 = speye(N-1,N) - spdiagm(ones(N-1),1,N-1,N)

D = [ kron(D1, speye(N)); kron(speye(N), D1) ]

i, j = N*1 + 2, N*7+7

b = zeros(N^2); b[i], b[j] = 1, -1

v = (D' * D) \ b

v[i] - v[j]

Output: 1.6089912417307288

I've tried to recreate exactly the same approach in Mathematica, here's what I have done:

n = 10;

grid = GridGraph[{n, n}];

i = n*1 + 2;

j = n*7 + 7;

b = ConstantArray[0, {n*n, 1}];

b[[i]] = {1};

b[[j]] = {-1};

incidenceMat = IncidenceMatrix[grid];

matrixA = incidenceMat.Transpose[incidenceMat];

v = LinearSolve[matrixA, b]

I feel very silly, but I must be missing something probably very obvious as LinearSolve does not manage to find a solution (for the chosen nodes the answer is know to be $1.608991...$, which is obtained by taking the potential difference between A and B since the current is set to 1).

Questions

Have I mis-interpreted something in my replication of the algorithm sample written in Julia?

It would be very interesting and useful if someone could comment on how extensible these approaches are to more general systems (2d, 3d and not only for lattices). For instance, which approaches would be more suitable to adopt in Mathematica for larger resistor networks (in terms of efficiency, as one would have to deal with very sparse matrices probably).

As a side-note, on the same Rosetta article, there are two alternative code snippets provided for Mathematica (which follows Maxima's approach, essentially similar to the one written Julia). In case someone is interested I include them here: (source for both)

gridresistor[p_, q_, ai_, aj_, bi_, bj_] :=

Block[{A, B, k, c, V}, A = ConstantArray[0, {p*q, p*q}];

Do[k = (i - 1) q + j;

If[{i, j} == {ai, aj}, A[[k, k]] = 1, c = 0;

If[1 <= i + 1 <= p && 1 <= j <= q, c++; A[[k, k + q]] = -1];

If[1 <= i - 1 <= p && 1 <= j <= q, c++; A[[k, k - q]] = -1];

If[1 <= i <= p && 1 <= j + 1 <= q, c++; A[[k, k + 1]] = -1];

If[1 <= i <= p && 1 <= j - 1 <= q, c++; A[[k, k - 1]] = -1];

A[[k, k]] = c], {i, p}, {j, q}];

B = SparseArray[(k = (bi - 1) q + bj) -> 1, p*q];

LinearSolve[A, B][[k]]];

N[gridresistor[10, 10, 2, 2, 8, 7], 40]

Alternatively:

graphresistor[g_, a_, b_] :=

LinearSolve[

SparseArray[{{a, a} -> 1, {i_, i_} :> Length@AdjacencyList[g, i],

Alternatives @@ Join[#, Reverse /@ #] &[

List @@@ EdgeList[VertexDelete[g, a]]] -> -1}, {VertexCount[

g], VertexCount[g]}], SparseArray[b -> 1, VertexCount[g]]][[b]];

N[graphresistor[GridGraph[{10, 10}], 12, 77], 40]