Mathematica has built-ins.

So one path is

polarGrad[f_] :=

Block[{r, th, grad, rot, assume},

assume = CoordinateChartData["Polar",

"CoordinateRangeAssumptions"][{r, th}];

rot = CoordinateTransformData["Polar" -> "Cartesian",

"OrthonormalBasisRotation", {r, th}];

grad = Grad[f[r, th], {r, th}, "Polar"];

grad = CoordinateTransform["Cartesian" -> "Polar",

Transpose[rot].grad];

Simplify[grad, assume]]

Assuming[V'[r] > 0, polarGrad[Function[{r, th}, V[r]]]]

{V'[r], th}

polarGrad[Function[{r, th}, r Sin[th]]]

That is already answered to another question on stackexchange.com.

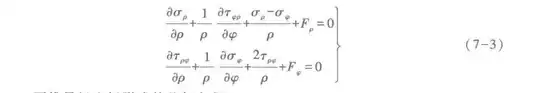

Following the given formula ()+=0:

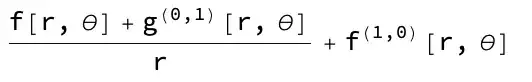

Div[{f[r, θ], g[r, θ]}, {r, θ}, "Polar"]

with σ[r, θ] = {f[r, θ], g[r, θ]}

an example is already in the documentation of Div

Div[{r Sin[θ], -r Cos[θ]}, {r, θ}, "Polar"]

3 Sin[θ]

Mind the representation of the force F is F_r e_r + F_Theta e_Theta.

The polar unit vector are local and take away usually parts of the r and Theta dependence from the representation of the force in different coordinate systems.

The divergence can be calculated from rank 2 tensors in a similar fashion.

Div[{{x y, x y^2, x y^3}, {x^2 y, x^2 y^2, x^2 y^3}, {x^3 y, x^3 y^2,

x^3 y^3}}, {x, y, z}]

{y + 2 x y, 2 x y + 2 x^2 y, 3 x^2 y + 2 x^3 y}

Since this question targets polar coordinates we calculate this task for a 2 x 2 matrix

{{x y, x y^2}, {x^2 y, x^2 y^2}}

transform the functions in the matrix elements with

x= r Sin[Theta]

y= r Cos[Theta]

{{r^2 Sin[Theta]Cos[Theta], r^3 Sin[Theta]Cos[Theta]^2}, {r^3 Sin[Theta^2]Cos[Theta], r^4 Sin[Theta]^2Cos[Theta]^2}}

Now apply the Div in polar coordinates to this matrix:

Div[{{r^2 Sin[Theta] Cos[Theta],

r^3 Sin[Theta] Cos[Theta]^2}, {r^3 Sin[Theta^2] Cos[Theta],

r^4 Sin[Theta]^2 Cos[Theta]^2}}, {r, θ}, "Polar"]

{2 r Cos[Theta] Sin[Theta] + (

r^2 Cos[Theta] Sin[Theta] - r^4 Cos[Theta]^2 Sin[Theta]^2)/r,

3 r^2 Cos[Theta] Sin[Theta^2] + (

r^3 Cos[Theta]^2 Sin[Theta] + r^3 Cos[Theta] Sin[Theta^2])/r}

This has to be equal to the resulting matrix in cartesian coordinates.

Div[{{x y, x y^2}, {x^2 y, x^2 y^2}}, {x, y}]

{y + 2 x y, 2 x y + 2 x^2 y}

This transformation to be applied makes use of the afore mention unit vector representation. Both are equal. {Sin[Theta],Cos[Theta]} for e_r and {Cos[Theta],-Sin[Theta]} for e_Theta.

TransformedField[

"Polar" ->

"Cartesian", {2 r Cos[θ] Sin[θ] + (r^2 Cos[θ] \

Sin[θ] - r^4 Cos[θ]^2 Sin[θ]^2)/r,

3 r^2 Cos[θ] Sin[θ^2] + (r^3 Cos[θ]^2 Sin[\

θ] + r^3 Cos[θ] Sin[θ^2])/

r}, {r, θ} -> {x, y}] // FullSimplify

This question is about path integrals. These are essential for the concept of the divergence:

line-integration-given-tangent-vector.

Mathematica does all its computations in an orthonormal basis. You simply need to specify what coordinate system you're working in. So for your example, you just multiply by {0, 0, 1}:

e[r_, θ_, ϕ_, t_] := (Sin[θ]/r)[Cos[r - t] - Sin[r - t]/r] {0, 0, 1}

Apparently this is a pure wave in vacuum, as the divergence is zero:

Div[e[r, θ, ϕ, t], {r, θ, ϕ}, "Spherical"]

0

Similarly, a pure Coulomb electric field would be

col[r_, θ_, ϕ_] := {1/r^2, 0, 0}

Div[col[r, θ, ϕ], {r, θ, ϕ}, "Spherical"]

0

I suggest you look at the tutorials tutorial/VectorAnalysis and tutorial/ChangingCoordinateSystems and the functions linked therefrom for more.

The built-in CoordinateTransformData holds all the data of interest.

The built-in TransformedField is a nice tool to the tedious calculations' interest.

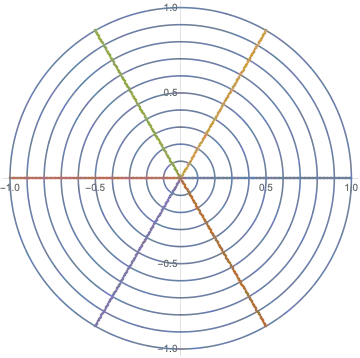

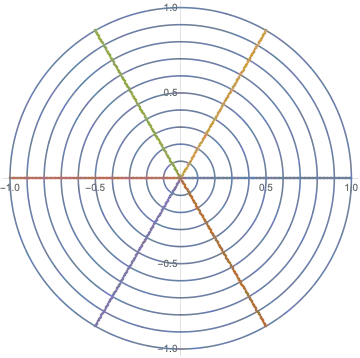

Polar coordinates have advantages if

a) the problem is two dimensional,

b) the symmetry is easily mappableenter link description here to this

Show[Table[

PolarPlot[r, {θ, -π, π}], {r, 0.1, 1., 0.1}],

ListPolarPlot[Table[Table[{m π/3, n/125}, {n, 125}], {m, 0, 5}]]]

These are interesting if

CoordinateTransformData[

"Cartesian" -> "Polar", "MappingJacobianDeterminant", {x, y}]

1/Sqrt[x^2 + y^2]

is advantageous and not a problem.

To work on a fruitful common basis with the formulas for plane stress I suggest this ElasticityBVP.