Edit

The answer is "ambiguous" because you have two parameters, $\alpha$ and $k$, and in this case the limit depends on the value of $\alpha$. What you can try is the following:

f[k_, α_] := ((k + 2) (α^2 - Sqrt[α^4 + k]) + k)/(α^2 - Sqrt[α^4 + k] + 2 k)

Simplify[Limit[f[k, α^(1/4)], k -> 0] /. α -> α^4, α ∈ Reals]

$\frac{2 \left(\alpha ^2-1\right)}{4 \alpha ^2-1}$

What I did is to remove all powers of $\alpha$ from under the square roots, so that the $k\to 0$ limit makes them look like $\sqrt{k+\alpha}\to \sqrt{\alpha}$ which manifestly cancels with the already present $\sqrt{\alpha}$ terms. At the end, I replace $\alpha$ by $\alpha^4$ to return to the original definition.

What follows below are the steps that led me to finally settle on the above approach. The upshot is that we have to avoid handing Mathematica expressions such as $\sqrt{\alpha^4}-\alpha^2 = 0$ because it doesn't simplify them at an early enough stage in the evaluation, even when the domain is real.

Initial answer

First assume simply that $\alpha$ is real:

Assuming[α ∈ Reals, Limit[f[k, α], k -> 0]]

2

Now say explicitly that $\alpha>0$:

Assuming[α > 0, Limit[f[k, α], k -> 0]]

$\frac{2 \left(\alpha ^2-1\right)}{4 \alpha ^2-1}$

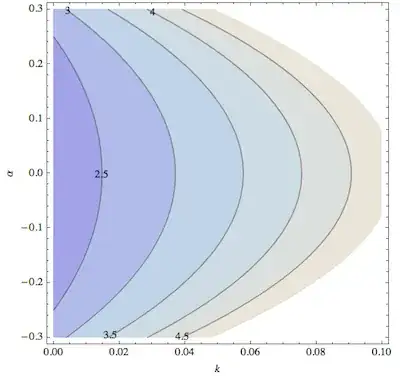

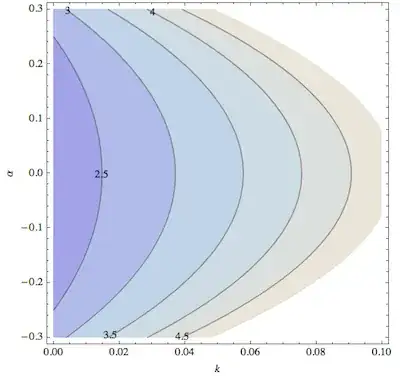

The behavior can be illustrated with a contour plot of f[k, α] around {0,0}:

ContourPlot[f[k, α], {k, 0, .1}, {α, -.3, .3}, FrameLabel -> {"k", "α"},

PlotRange -> {1, 5}, ContourLabels -> True]

In the plane of $k, \alpha$, Mathematica acts as if it preferred to choose the "easiest" approach to the $k=0$ axis by taking $\alpha = 0$ in the first case. But what it should have done is to return the more general result, or a ConditionalExpression (not necessary in this particular case because the general result goes smoothly to 2 for $\alpha\to0$).

The first result is a bug, I would say: Since $\alpha$ is a constant while the limit is taken, setting it to zero when it's allowed to be any real number is just too restrictive. This preliminary conclusion that it's a bug is strengthened below where I try to understand why it may be happening, and whether the function f[k, α] can be made to look less pathological before doing the limit.

Work-around

From the comments in the other answers, it is clear that Mathematica doesn't use the assumption of real variables at a sufficiently early stage in the calculation. You can even see that without taking any limit:

f[0, α]

2

The reason for this result is that it can't see the simplification $\sqrt{\alpha^4}-\alpha^2 = 0$ which is always true for real $\alpha$. It knows this fact, but isn't using it. To check this, we can do

Refine[0 == (Sqrt[α^4] - α^2), α ∈ Reals]

True

If this guess about the bug is right, then it's basically a problem of the order of two non-commuting limits. In addition to doing $k\to0$, the assumption of real $\alpha$ amounts to taking the limit $\Im(\alpha)\to 0$ (zero imaginary part). If you do the latter limit last, it gives $2$, but we are interested in the opposite order of limits.

To avoid this problem, one can eliminate the variable $k$ in terms of a new variable that gets rid of the square root:

First transform to variables $x=\sqrt{k}$ and $y=\alpha^2$ to end up with at most squares:

Clear[g];

g[x, y] = Simplify[f[x^2, Sqrt[y]]]

$\frac{\left(x^2+2\right)\left(y-\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\right)+x^2}{-\sqrt{x^2+y^2}+2x^2+y}$

Next, define a third new variable $z\equiv y-\sqrt{x^2+y^2}$ that incorporates the unwanted square root,

newg = g/.First@Solve[Eliminate[{g == g[x, y], z == -Sqrt[x^2 + y^2] + y}, x],g]

$\frac{2 y z+2 y-z^2-z-2}{4 y-2 z-1}$

Finally, observe that the limit $k\to0$ is the same as the limit $z\to0$ provided that we make the assumption $\lim_{x\to 0}(y-\sqrt{x^2+y^2})=0$ (which is true because $y\ge0$). Therefore, we can take the desired limit by setting

newg /. z -> 0

$\frac{2 y-2}{4 y-1}$

This is the correct limit if we reinstate $y=\alpha^2$. Note that I didn't have to use Limit at all because the function is well-behaved in this simplified form.