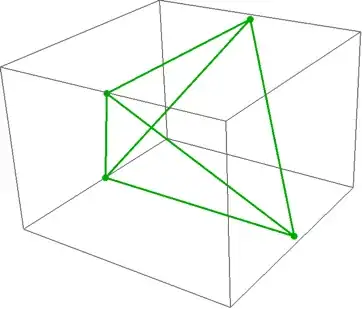

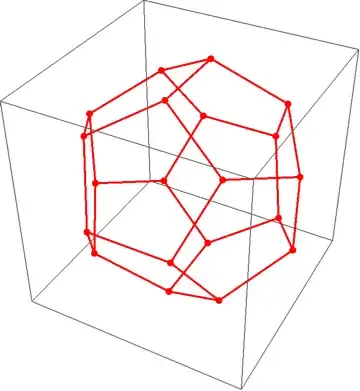

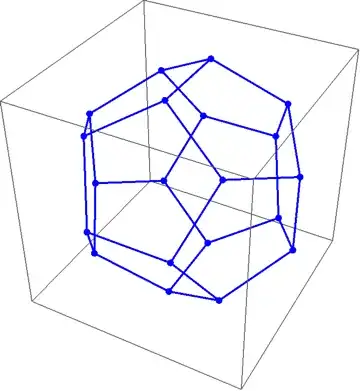

My question is: how to find the coordinates of the vertices of regular tetrahedron and dodecahedron? I tried to find the coordinates of the vertices of a regular tetrahedron as the solutions of a certain polynomial system in $8$ variables, notating the vertices of a tetrahedron $S(0,0,1)$, $A(0,yA,zA)$, $B(xB,yB,zB)$, and $C(xC,yC,zC)$:

Reduce[

yA^2 + zA^2 == 1 &&

xB^2 + yB^2 + zB^2 == 1 &&

xC^2 + yC^2 + zC^2 == 1 &&

yA^2 + (zA - 1)^2 == xB^2 + yB^2 + (zB - 1)^2 &&

yA^2 + (zA - 1)^2 == xC^2 + yC^2 + (zC - 1)^2 &&

xB^2 + (yB - yA)^2 + (zB - zA)^2 ==

xC^2 + (yC - yA)^2 + (zC - zA)^2 &&

xB^2 + (yB - yA)^2 + (zB - zA)^2 ==

(xC - xB)^2 + (yC -yB)^2 + (zC - zB)^2 &&

xB^2 + (yB - yA)^2 + (zB - zA)^2 ==

yA^2 + (zA - 1)^2,

{xB, xC, yA, yB, yC, zA, zB, zC}, Reals]

However, that code is spinning for hours without any output. A new idea is required.

P.S. 12.12.13. The answer done with Maple can be seen at http://mapleprimes.com/questions/200438-Around-Plato-And-Kepler-Again. Because nothing but trigonometry is used, I am pretty sure all that is possible in Mathematica.

PolyhedronDataunless you are genuinely interested in calculating the vertices. – C. E. Dec 10 '13 at 15:25PolyhedronData["Tetrahedron"] // Cases[#, GraphicsComplex[x_, _] :> x] &. – Stephen Luttrell Dec 10 '13 at 19:20