It always takes me a while to remember the best way to do a numerical Fourier transform in Mathematica (and I can't begin to figure out how to do that one analytically). So I like to first do a simple pulse so I can figure it out. I know the Fourier transform of a Gaussian pulse is a Gaussian, so

pulse[t_] := Exp[-t^2] Cos[50 t]

Now I set the timestep and number of sample points, which in turn gives me the frequency range

dt = 0.05;

num = 2^12;

df = 2 π/(num dt);

Print["Frequency Range = +/-" <> ToString[num/2 df]];

Frequency Range = +/-62.8319

Next create a timeseries list, upon which we will perform the numerical transform

timevalues =

RotateLeft[Table[t, {t, -dt num/2 + dt, num/2 dt, dt}], num/2 - 1];

timelist = pulse /@ timevalues;

Notice that the timeseries starts at 0, goes up to t=num dt/2 and then goes to negative values. Try commenting out the RotateLeft portion to see the phase it introduces to the result. We will have to RotateRight the resulting transform, but it comes out correct in the end. I define a function that Matlab users might be familiar with,

fftshift[flist_] := RotateRight[flist, num/2 - 1];

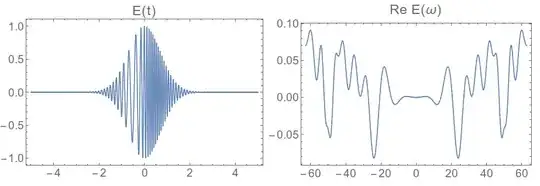

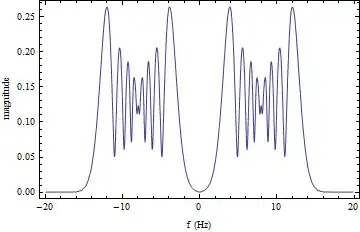

Grid[{{Plot[pulse[t], {t, -5, 5}, PlotPoints -> 400,

PlotLabel -> "E(t)"],

ListLinePlot[Re@fftshift[Fourier[timelist]],

DataRange -> df {-num/2, num/2}, PlotLabel -> "E(ω)"]}}]

which is what we were expecting. So now we try it on the more complicated pulse,

pulse[t_] := Exp[-t^2] Cos[50 t - Exp[-2 t^2] 8 π];

timelist = pulse /@ timevalues;

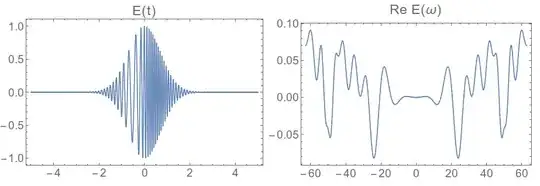

Grid[{{Plot[pulse[t], {t, -5, 5}, PlotPoints -> 400,

PlotLabel -> "E(t)"],

ListLinePlot[Re@fftshift[Fourier[timelist]],

DataRange -> df {-num/2, num/2}, PlotLabel -> "Re E(ω)"]}}]

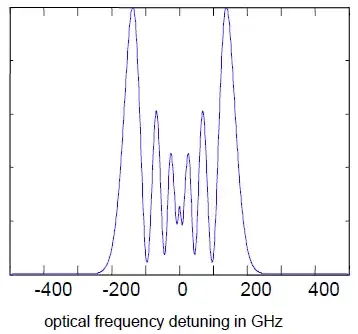

That doesn't look right ,the spectrum doesn't go to zero at the outer edges. We need more bandwidth on our transform, which we can get by decreasing the timestep

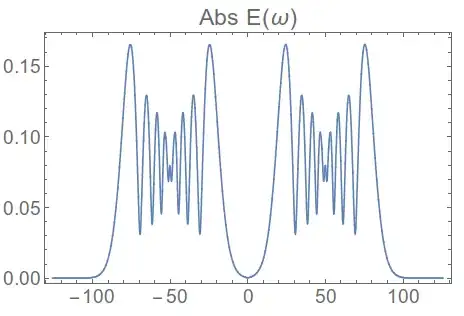

dt = 0.025;

df = 2 π/(num dt);

timevalues :=

RotateLeft[Table[t, {t, -dt num/2 + dt, num/2 dt, dt}], num/2 - 1];

timelist = pulse /@ timevalues;

ListLinePlot[Re@fftshift[Fourier[timelist]], DataRange -> df {-num/2, num/2}, PlotLabel -> "Re E(ω)"]}}]

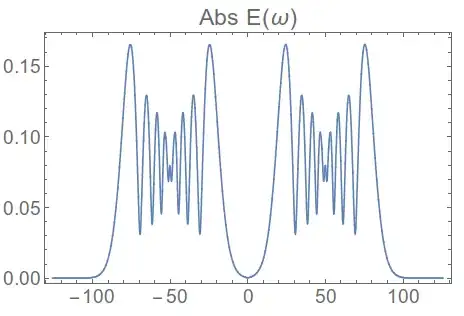

Or, if you want the power spectrum,

ListLinePlot[Abs@fftshift[Fourier[timelist]], DataRange -> df {-num/2, num/2}, PlotLabel -> "Abs E(ω)"]

Edit:

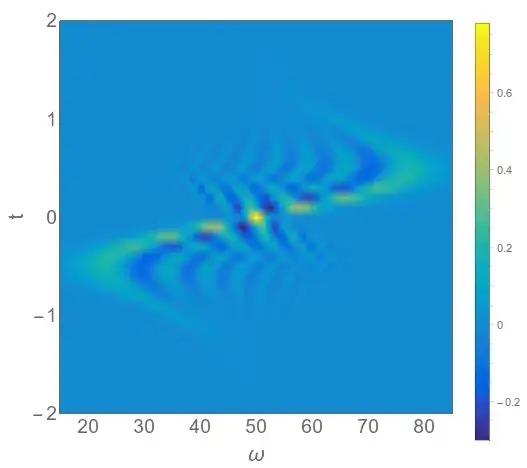

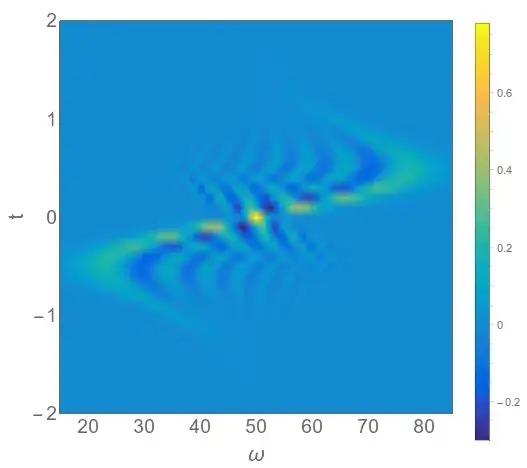

Besides looking at the optical pulse in the two conjugate domains, time and frequency, it is also possible to look at mixed time/frequency representations. I wrote a function to numerically find the Wigner function for this pulse, defined as

$$ W_x(t,\omega) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty E(t+\frac{\tau}{2}) E ^*(t-\frac{\tau}{2}) e^{-i \omega\, \tau} \, d\tau$$

and here is the plot

You can see how the frequency dips below 50 at short negative times, then goes above 50 for short positive times. This follows from the fact that the frequency is defined as the derivative of the phase function, which in this case goes as

\begin{align}\omega(t) =& \frac{d\phi}{dt}(t) \\

=& (32 \pi) \,t \,e^{-2 t^2} + 50

\end{align}

and this is the shape of the curve we see along the vertical axis of the 2D plot above.