Note that if $\pi$ were rational (with even numerator), then $\sin(n)$ would equal $1$ periodically, so the series would diverge. Similarly if $\pi$ were a sufficiently strong Liouville number. Thus, to establish convergence, one must use some quantitative measure of the irrationality of $\pi$.

It is known that the irrationality measure $\mu$ of $\pi$ is finite (indeed, the current best bound is $\mu \leq 7.60630853$). Thus, one has a lower bound

$$ | \pi - \frac{p}{q} | \gg \frac{1}{q^{\mu+\varepsilon}}$$

for all $p,q$ and any fixed $\varepsilon>0$. This implies that

$$ \mathrm{dist}( p/\pi, \mathbf{Z}) \gg \frac{1}{p^{\mu-1+\varepsilon}},$$

for all large $p$ (apply the previous bound with $q$ the nearest integer to $p/\pi$, multiply by $q/\pi$, and note that $q$ is comparable to $p$). In particular, if $I \subset {\bf R}/{\bf Z}$ is an arc of length $0 < \delta < 1$, the set of $n$ for which $n/\pi \hbox{ mod } 1 \in I$ is $\gg \delta^{-1/(\mu-1+\varepsilon)}$-separated. This implies, for any natural number $k$, that the number of $n$ in $[2^k,2^{k+1}]$ such that $|\sin(n)|$ lies in any given interval $J$ of length $2^{-k}$ (which forces $n/\pi \hbox{ mod } 1$ to lie in the union of at most two intervals of length at most $O(2^{-k/2})$) is at most $\ll 2^{k(1 - \frac{1}{2(\mu-1+\varepsilon)})}$, the key point being that this is a "power saving" over the trivial bound of $2^k$. Noting (from Taylor expansion) that $|\sin(n)|^n \ll \exp( - j)$ if $n \in [2^k,2^{k+1}]$ and $|\sin(n)| \in [1 - \frac{j+1}{2^k}, 1-\frac{j}{2^k}]$, we conclude on summing in $j$ that

$$ \sum_{2^k \leq n < 2^{k+1}} |\sin(n)|^n \ll 2^{k(1 - \frac{1}{2(\mu-1+\varepsilon)})}$$

and hence

$$ \sum_{2^k \leq n < 2^{k+1}} \frac{|\sin(n)|^n}{n} \ll 2^{- k\frac{1}{2(\mu-1+\varepsilon)}}.$$

The geometric series on the RHS is summable in $k$, so the series $\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{|\sin(n)|^n}{n}$ is convergent. (In fact the argument also shows the stronger claim that $\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{|\sin(n)|^n}{n^{1-\frac{1}{2(\mu-1+\varepsilon)}}}$ is convergent for any $\varepsilon>0$.)

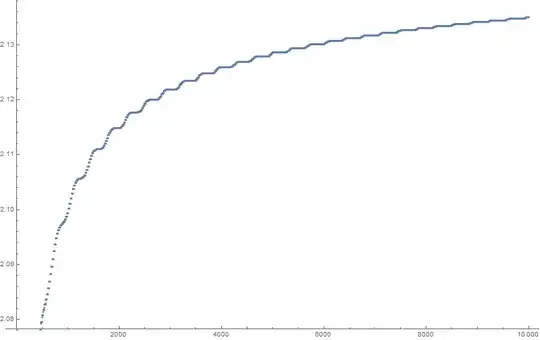

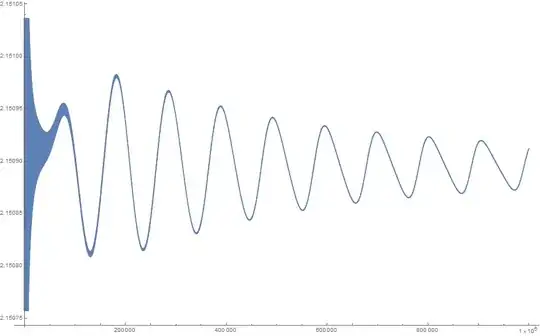

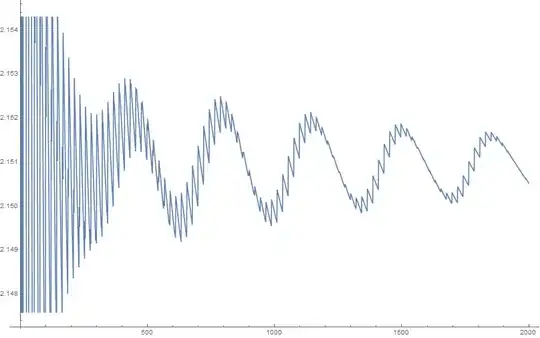

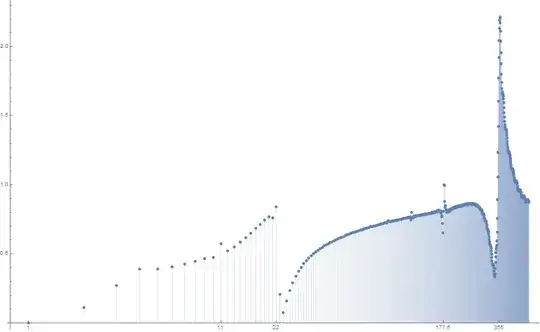

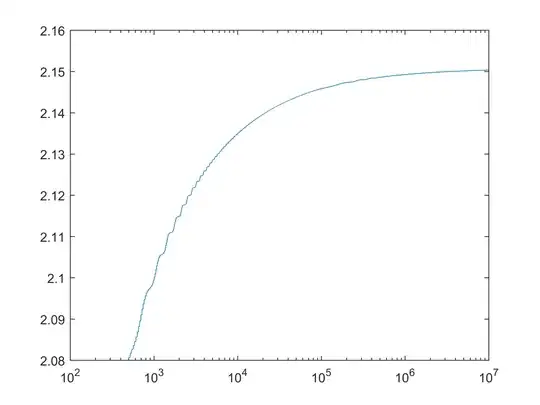

EDIT: the apparent numerical divergence of the series may possibly be due to the reasonably good rational approximation $\pi \approx 22/7$, which is causing $|\sin(n)|$ to be close to $1$ for $n$ that are reasonably small odd multiples of $11$. UPDATE: I now agree with Will that it is the growth of $-2^{3/2}/\pi^{1/2} n^{1/2}$, rather than any rational approximant to $1/\pi$, which was responsible for the apparent numerical divergence at medium values of $n$, as is made clear by the updated numerics on another answer to this question.