Thank you for your interest in my views on the set-theoretic

multiverse.

Yes, indeed, the well-foundedness mirage axiom you mention is

probably the most controversial of my multiverse axioms, and so

allow me to explain a little about it.

The axiom expresses in a strong way the idea that we don't actually

have a foundationally robust absolute concept of the finite in

mathematics. Specifically, the axiom asserts that every universe of

set theory is ill-founded even in its natural numbers from the

perspective of another, better universe. Thus, every set-theoretic

background in which we might seek to undertake our mathematical

activity is nonstandard with respect to another universe.

My intention in posing the axiom so provocatively was to point out

what I believe is the unsatisfactory nature of our philosophical

account of the finite.

You might be interested in the brief essay I wrote on the topic, A

question for the mathematics

oracle,

published in the proceedings of the Singapore workshop on Infinity

and Truth. For an interesting and entertaining interlude, the

workshop organizers had requested that everyone at the workshop

pose a specific question that might be asked of an all-knowing

mathematical oracle, who would truthfully answer. My question was

whether in mathematics we really do have a absolute concept of the

finite.

To explain a bit more, the naive view of the natural numbers in

mathematics is that they are the numbers, $0$, $1$, $2$, and so

on. The natural numbers, with all the usual arithmetic structure,

are taken by many to have a definite absolute nature; arithmetic

truth assertions are taken to have a definite absolute nature, in

comparison for example with the comparatively less sure footing of

set-theoretic truth assertions.

To be sure, many mathematicians and philosophers have proposed a

demarcation between arithmetic and analysis, where the claims of

number theory and arithmetic are said to have a definite absolute

nature, while the assertions of higher levels of set theory,

beginning with claims about the set of sets of natural numbers, are

less definite. Nik Weaver, for example, has suggested that

classical logic is appropriate for the arithmetic realm and

intuitionistic logic for the latter realm, and a similar position

is advocated by Solomon Feferman and others.

But what exactly does this phrase, "and so on" really mean in the

naive account of the finite? It seems truly to be doing all the

work, and I find it basically inadequate to the task. The situation

is more subtle and problematic than seems to me to be typically

acknowledged. Why do people find their conception of the finite to

be so clear and absolute? It seems hopelessly vague to me.

Of course, within the axiomatic system of ZFC or other systems, we

have a clear definition of what it means to be finite. The issue is

not that, but rather the extent to which these internal accounts of

finiteness agree with the naive pre-reflective accounts of the

finite as used in the meta-theory.

Some mathematicians point to the various categoricity arguments as

an explanation of why it is meaningful to speak of the natural

numbers as a definite mathematical structure. Dedekind proved,

after all, that there is up to isomorphism only one model

$\langle\mathbb{N},S,0\rangle$ of the second-order Peano axioms,

where $0$ is not a successor, the successor function $S$ is

one-to-one, and $\mathbb{N}$ is the unique subset of $\mathbb{N}$

containing $0$ and closed under successor.

But to my way of thinking, this categoricity argument merely pushes

off the problem from arithmetic to set theory, basing the

absoluteness of arithmetic on the absoluteness of the concept of an

arbitrary set of natural numbers. But how does that give one any

confidence?

We already know very well, after all, about failures of

absoluteness in set theory. Different models of set theory can

disagree about whether the continuum hypothesis holds, whether the

axiom of choice holds, and so with innumerable examples of

non-absoluteness. Different models of set theory can disagree on

their natural number structures, and even when they agree on their

natural numbers, they can still disagree on their theories of

arithmetic truth (see Satisfaction is not

absolute).

So we know all about how mathematical truth assertions can seem to

be non-absolute in set theory.

Skolem pointed out that there are models of set theory $M_1$, $M_2$

and $M_3$ with a set $A$ in common, such that $M_1$ thinks $A$ is

finite; $M_2$ thinks $A$ is countably infinite and $M_3$ thinks $A$

is uncountable. For example, let $M_3$ be any countable model of

set theory, and let $M_1$ be an ultrapower by a ultrafilter on

$\mathbb{N}$ in $M_3$, and let $A$ be a nonstandard natural number

of $M_1$. So $M_1$ thinks $A$ is finite, but $M_3$ thinks $A$ has

size continuum. If $M_2$ is a forcing extension of $M_3$, we can

arrange that $A$ is countably infinite in $M_2$.

No amount of set-theoretic information in our set-theoretic

background could ever establish that our current conception of the

natural numbers, whatever it is, is the truly standard one, since

whatever we assert to be true is also true in some nonstandard

models, whose natural numbers are not standard.

The well-foundedness mirage axiom asserts that this phenomenon is

universal: all universes are wrong about well-foundedness.

In defense of the mirage axiom, let me point out that whatever attitude toward it one might harbor, nevertheless the axiom cannot be seen as incoherent or inconsistent, because Victoria Gitman and I have proved that all of my multiverse axioms are true in the multiverse consisting of the countable computably saturated models of ZFC. So the axiom is neither contradictory nor incoherent. See A natural model of the multiverse axioms.

I have discussed my multiverse views in several papers.

Hamkins, Joel David, The set-theoretic multiverse, Rev. Symb. Log. 5, No. 3, 416-449 (2012). Doi:10.1017/S1755020311000359, ZBL1260.03103.

<p><em>Hamkins, Joel David</em>, <a href="http://jdh.hamkins.org/multiverse-perspective-on-constructibility/" rel="noreferrer"><strong>A multiverse perspective on the axiom of constructibility</strong></a>, Chong, Chitat (ed.) et al., Infinity and truth. Based on talks given at the workshop, Singapore, July 25--29, 2011. Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific (ISBN 978-981-4571-03-6/hbk; 978-981-4571-05-0/ebook). Lecture Notes Series. Institute for Mathematical Sciences. National University of Singapore 25, 25-45 (2014). <a href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/9789814571043_0002" rel="noreferrer">DOI:10.1142/9789814571043_0002</a>,

<a href="https://zbmath.org/?q=an:1321.03061" rel="noreferrer">ZBL1321.03061</a>.</p>

<p><em>Gitman, Victoria; Hamkins, Joel David</em>, <a href="http://jdh.hamkins.org/naturalmodelofmultiverseaxioms/" rel="noreferrer"><strong>A natural model of the multiverse axioms</strong></a>, Notre Dame J. Formal Logic 51, No. 4, 475-484 (2010). <a href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/00294527-2010-030" rel="noreferrer">DOI:10.1215/00294527-2010-030</a>, <a href="https://zbmath.org/?q=an:1214.03035" rel="noreferrer">ZBL1214.03035</a>.</p>

<p><em>Hamkins, Joel David; Yang, Ruizhi</em>, <a href="http://jdh.hamkins.org/satisfaction-is-not-absolute/" rel="noreferrer"><strong>Satisfaction is not absolute</strong></a>, to appear in the Review of Symbolic Logic.</p>

But finally, to address your specific question. Of course, there

are specific finite numbers that will be finite with respect to any

alternative set-theoretic background. As Michael Greinecker points

out in the comments, the number 35253586543 has that value

regardless of your meta-mathematical position. So of course, there

are many proofs that are standard finite with respect to any of the

alternative foundations.

Meanwhile, I find it very interesting to consider the situation

where different foundational systems disagree on what is provable.

In very recent work of mine, for example, we are looking at the

theory of set-theoretic and arithmetic potentialism, where

different foundational systems disagree on what is true or

provable.

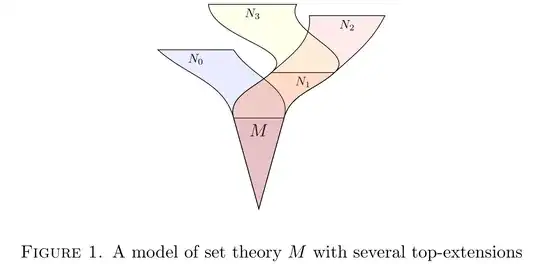

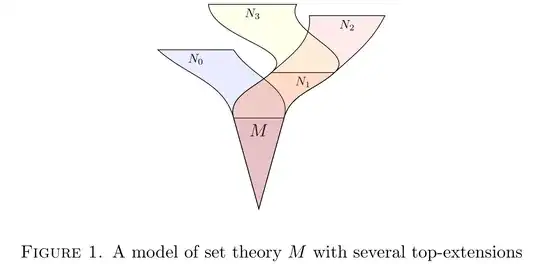

For example, recently with Hugh Woodin, I have proved that there is

a universal finite set $\{x\mid\varphi(x)\}$, a set that ZFC proves

is finite, and which is empty in any transitive model of set

theory, but if the set is $y$ in some countable model of set theory

$M$ and $z$ is any finite set in $M$ with $y\subset z$, then there

is a top-extension of $M$ to a model $N$ inside of which the set is

exactly $z$. The key to the proof is playing with the non-absolute

nature of truth between $M$ and its various top-extensions.