Here is a counterexample to the first question, a planar, non-separating one-dimensional locally connected continuum.

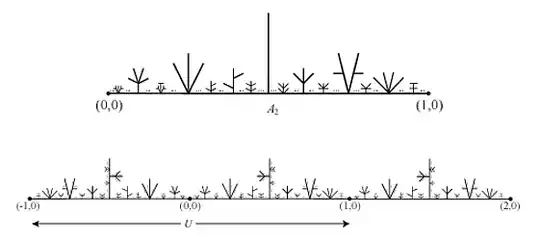

Let $A_1$ be the line segment in the $xy$-plane $\mathbb{R}^2$ with end points $(0,0)$ and $(1,0)$. Define set $A_2$ as the union of $A_1$ with a sequence of mutually disjoint trees (finite acyclic graphs) $T_i$, no two of them homeomorphic, each attached to $A_1$ at a single point other than the end point of $A_1$. The diameters of the trees should converge to zero, and the set of points of attachment should be dense in $A_1$ (see the first drawing). Also, $A_2\setminus A_1$ should be contained in the vertical open strip $0<y<1$.

Observe now that every homeomorphism of $A_2$ onto itself must be the identity on $A_1$.

Next, to construct $A_3$, to each edge of every tree attached to $A_1$, attach a sequence of trees at a single point of the edge, in a similar manner as previously, and iterate this procedure, creating a nested sequence of sets $A_n$, each of which is a tree. Make sure that the diameters of the union $A=A_1\cup A_2\cup A_3\ldots$ is bounded, that the only points of $A$ lying on the boundary of the open strip $0<y<1$ are the end points of $A_1$. Also, make sure that the closure of $A$ (in $\mathbb{R}^2$), which we call $B$, does not contain any simple closed curve. This last requirement can be satisfied by designing the trees attached in the recursive procedure to be sufficiently small.

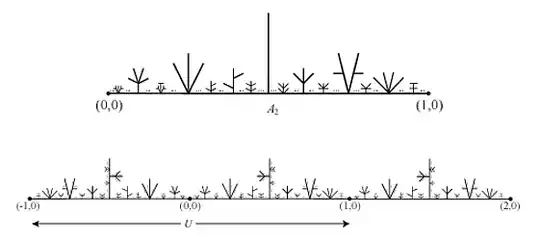

It is easy to see that every homeomorphism of $A_3$ onto itself must keep every point of $A_2$ fixed, and under any homeomorphism of $B$ onto itself, each point of $A_n$ must be fixed. Hence $B$ is rigid. Let $B’$ be the reflection of $B$ in the $y$-axis, let $X=B\cup(B’)\cup(B+(1,0))$, and let $U=[B\cup(B’)]\setminus\{(-1,0),(1,0)\}$ (see the second drawing). Here is the open set $U$, in the rigid space $X$, and it is not rigid, since it is symmetric about the $y$-axis.

Note 1. The set $B$ can also be described as the inverse limit of the nested sequence $\{A_n\}\ (n=1,2,\ldots)$ with the obvious retractions $r_n$ from $A_{n+1}$ to $A_n$, collapsing each tree in $A_{n+1}$ attached to $A_n$ to its point of attachment, as the bonding maps.

Note 2. In each stage of the construction a sequence of trees is used. In all, a countable number of trees appear; we may assume that all of them are mutually non-homeomorphic, though it is not quite necessary.