An approach to studying that works with many branches of mathematics is to learn the prerequisites first, then study a good textbook on the subject.

For instance, one could study subjects like algebra, measure theory, smooth manifolds, functional analysis in this manner.

Although a textbook on the subject can include examples from other subjects that one has not studied yet,

the presence of such examples typically does not prevent one from successfully mastering the particular subject under consideration.

(I would say that a good textbook should certainly try to include connections to other areas and not portray its subject as an isolated field.)

For category theory, taking such a route can be quite difficult.

Indeed, the (formal) prerequisites are almost nonexistent: elementary logic and set theory will do.

But such simplicity can be deceiving.

For instance, the notion of a Kan extension can be very puzzling

until one learns a few specific nontrivial examples, such as pushforward and pullback maps for sheaves,

various geometric realization functors, or quantization of Dijkgraaf–Witten theories.

Even the definitions of relatively simple notions, such as equivalence of categories

may convey a rather deceiving picture of their importance,

until one learns some really deep examples of equivalences of categories,

such as the Gelfand duality, Hahn–Banach theorem, spectral theorem for normal operators, Pontrjagin duality, Serre–Swan theorem, GAGA, or second and third Lie theorems.

As may be obvious from the above examples, it may be difficult to present category theory with sufficient

motivation without making considerable use of other areas.

This immediately presents a serious problem: from what areas one should draw examples?

Trying to cover all of mathematics is too hard.

Concentrating on examples from a specific area (e.g., algebra, like some books on category theory do)

immediately creates its own problems: an analyst reading a category theory textbook with examples from algebra

may not see much value in it, since it does not seem to relate directly to analysis.

Thus, one point of view is that the best way to learn category theory is to study other branches of mathematics that actively use categorical concepts.

Here are some textbooks that present their subject using categorical tools where appropriate:

Algebra: Paolo Aluffi. Algebra. Chapter 0. Graduate Studies in Mathematics 104 (2009).

Algebraic topology: Tammo tom Dieck. Algebraic Topology. EMS Textbooks in Mathematics (2008).

Functional analysis: Alexander Helemskii. Lectures and Exercises on Functional Analysis. Translations of Mathematical Monographs 233 (2006).

Elementary set theory: F. William Lawvere, Robert Rosebrugh. Sets for Mathematics. Cambridge University Press (2003).

General topology: Tai-Danae Bradley, Tyler Bryson, John Terilla. Topology. A Categorical Approach. MIT Press (2020).

Elementary topology: Ronald Brown. Topology and Groupoids. BookSurge (2006).

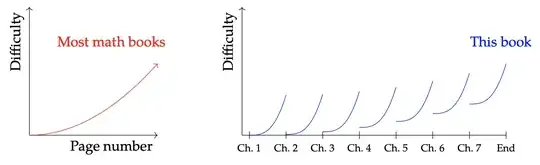

Once you are familiar with a few subjects that use category theory,

you may want to solidify your knowledge by studying categories more systematically.

Of the available books, the better one in terms of size and selection of material appears to be