Let $P\subset \Bbb R^n$ be an inscribed convex polytope, that is, all its vertices are on a common sphere of radius $r$. Let $G$ be the edge-graph of $P$. For convenience, assume $V(G)=\{1,\dotsc,s\}$. Let $\ell_{ij}$ denote the length of the edge of $P$ corresponding to $ij\in E(G)$.

Question. Let $p_1,\dotsc,p_s\in\Bbb R^{m}$ be points so that

- the points are on a common sphere $S$,

- $\lVert p_i-p_j\rVert\le\ell_{ij}$ for all $ij\in E(G)$,

- the center of $S$ lies in the convex hull $\operatorname{conv}\{p_1,\dotsc,p_s\}$.

Is it then true that the radius of $S$ is at most $r$? If no, does this change if $n=m$?

In other words, are the skeleta of inscribed polytopes "as expanded as possible" for the given edge-lengths?

Note that the condition on the convex hull is necessary. Without this we could choose an arbitrarily large sphere $S$, and place all the $p_1,\dotsc,p_s$ in an arbitrarily small patch of $S$, so that $S$ is their circumsphere.

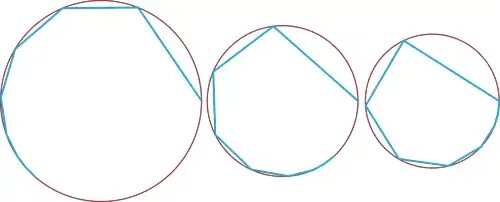

The case $n=m=2$

I will demonstrate my general ideal on the case $n=m=2$, which I hope to somehow generalize to all cases with $n=m$. I do not yet have an idea for $m>n$.

Let $P\subset\Bbb R^2$ be an inscribed polygon with circumradius $r$ and vertices $v_1,...,v_s$ in circular order. Let $\alpha_i$ be the angle between $v_i$ and $v_{i+1}$ (indices mod $s$) as seen from the circumcenter. Then $\alpha_1+\dots+\alpha_s=2\pi$.

Suppose now that we have such a set of points $p_1,...,p_s$ with circumradius $r'>r$. Let $\beta_i$ be the angle between $p_i$ and $p_{i+1}$ as seen from the circumcenter. Since $\|p_i-p_{i+1}\|\le \|v_i-v_{i+1}\|$ but also $\|p_i\|>\|v_i\|$ it is easy to see that $\beta_i<\alpha_i$. In particular, $\beta_1+\cdots+\beta_s<2\pi$, and the closed polyline with vertices $p_1,...,p_s$ must have zero winding number around the circumcenter. But since the convex hull of the $p_i$ contains the origin, there are three points $p_{i_1},p_{i_2},p_{i_3}$ with $i_1<i_2<i_3$ so that already the convex hull of these contains the circumcenter. It is then easy to see that $$\beta_{i_1}+\cdots+\beta_{i_2}+\cdots+\beta_{i_3}\ge \pi$$ and $$\beta_{i_3+1}+\beta_{i_3+2}+\cdots+\beta_{i_1-1}\ge \pi,$$ in contradiction to $\beta_1+\cdots+\beta_s<2\pi$. $\;\square$

To generalize this, one would need to find a suitable notion of "winding number" (mapping degree) for point arrangements with $n>3$, somehow using the face structure provided by the polytope. One might then be able to construct a similar argument using space angles (aka fractions of the sphere, as described by Matt F. in the comments).