I've completely changed my mind but I leave the old answer to explain the comments.

It seems quite likely that there is a choice of residues which misses only the 40 integers

$1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 14, 15, 18, 20, 21, 23, 29, 30, 33, 36, 41, 44,51, $

$ 53, 54, 56, 63, 65, 68, 69, 71, 75, 78, 81, 84, 86, 90, 93, 95, 96, 98, 99.$

It arises from the following semi-greedy procedure:

Only worry about integers starting with $s=100$ ($s=90$ is not enough).

At each step, take the smallest integer $t \ge s$ not yet covered and attempt to cover it with the smallest unused odd prime $p$ such that $t+p$ is also not yet covered and $p \le t.$

If there is no such prime then simply use the smallest unused prime (if it is less than $t$, otherwise, STOP!).

Whatever prime is chosen, take the arithmetic progression $A=r+np$ for $n \ge 1$ where $t \bmod{p} =r$

So $1+3n$ knocks out $100,103,106,109,112,115,118,121\dots$ leaving $101$ next. Since $106$ is already covered we use $3+7n$ covering $101,108,122 \dots$ now $2+5n$ works for $102,107,117 \dots$ Next is $104$ and since $104+p$ is covered for $p=11,13,17$ we use $9+19n$.

The residues chosen start out

$[3, 1], [7, 3], [5, 2], [19, 9], [11, 6], [31, 17], [17, 9], [13, 9], [41, 32], [37, 8], [53, 14],$

$ [43, 39], [67, 64], [61, 12], [23, 20], [79, 61], [89, 55], [103, 43], [47, 12], [29, 14]$

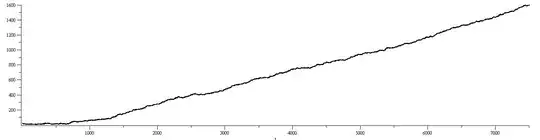

Details: I followed this procedure using the $5132$ odd primes up to $49999.$ The number of unused primes less than $t$ (the first uncovered integer) starts at 24 when $t=100.$ It gets as low as 7 a few times, the last being when $t=1419.$ After $t=4925$ there are always at least $10$ unused primes below $t$ and from then on it seems to grow fairly steadily. After $t=33338$ there are (as far as I went) at least $500$ unused primes and after 4341 steps, $t=49980$ with $789$ unused primes available. I used up the remaining primes under $50{,}000$ (without checking if larger primes would be preferred by step 2)

At step $5132$ the prime $43973$ was used for $t=60465.$ This left things with next target $t=60471$ and all $965$ primes $50000 \lt p \lt 60471$ as yet unused.

Other starting values $s$ and the $t$ at which there is no available prime left are:

$[10, 24], [20, 55], [30, 146], [40, 189], [50, 393], [60, 553], [70, 935], [80, 1969], [90, 4898].$

A pure greedy strategy of starting at say $s=1000$ and always using the smallest unused odd prime seems to fail fairly quickly (perhaps in about $s$ steps.) The semi-greedy procedure stems from the idea that the main obstacle is the smallest uncovered integers.

It may be better to not wait too long to use the smallest unused prime. Alternately, it might be better to look a little further in hopes of having $t$ along with two of

$t+p,t+2p,t+3p$ all newly covered.

Old answer (this is left only to explain the comments)

I'll mildly change the notation without changing the question.

For every prime $p_i>p_0=2$ choose a residue $0 \le r_i\lt p_i$ and take the arithmetic progression $A_i=r_i+np_i$ $n \gt 0$ . Let $M=\mathbb{N} \backslash \bigcup A_i $ be the finite or infinite set of missed integers and $m_j$ be the $j$th member of $M$ (set $m_j=\infty$ if $M$ has less than $j$ elements). Once we have the residues up to $r_i$ we do know $M \cap \lbrace 1,2,\cdots,p_{i+1}-1 \rbrace$ and hence $m_j$ up to some point. So $m_0...m_5$ could be $1,2,4,8,16$ but only if we chose $r_1=0$ the first $5$ times. Otherwise we could have $1,2,4,m_4,m_5$ for $m_5 \le 13.$ If we take $r_1=1$ then can begin $1,2,3,6,9,12$ (the next choice is for $p_5=13$)

The greedy procedure is to take $r_i=0$ and get $m_j=2^j.$ The choices $r_i=1$ gives $m_j=2^j+1.$ Gerry suggests taking $r_1=1$ and then making greedy choices. Up to $p_{30}=127$ this gives the $r$ values $1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 2, 0, 3, 7, 2, 0, 4, 1, 1, 3, 2, 5, 3, 8, 4, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1$ and $m$ values $1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 26, 42, 56, 86, 87, 93, 96, 117, 122, 126$ This does not even look like exponential growth (even if extended to $p_{96}=509$. It seems that $r_1=2$ followed by greedy choices might be a little better but still subexponential.

I made the rash

claim: no matter how the $r_i$ are chosen, $m_j \le 2^j.$

NOTE: if my newer conjecture is true then for my chosen residues, $m_{40}=99$ but $m_{41}=\infty$

I made the even rasher claim below but Noam shut it down decisively.

claim: no matter how the $r_i$ are chosen, every integer interval $[x,2x-1]$ contains an $m$ value.