Consider the following setup:

Two massive bodies of mass $M$ are fixed at the positions $\vec{A}=(d, 0)$ and $\vec{B}=(-d, 0)$.

Now imagine a test particle $p$ with initial position $\vec{r}_0=(x_0,y_0)$ and initial velocity $\vec{v}_0=(0,0)$. Its position $\vec{r}(t)=\left(x(t),y(t)\right)$ will change over time under the influence of the gravitational potential. If the test particles trajectory goes through $A$ (or $B$) the initial position $\vec{r}_0$ lies in the basin of attraction of the mass at point $A$ (or $B$).

Question: Does $x_0 \gt 0$ imply that $p$ will eventually come arbitrarily close to $A$ (and not $B$)?

Or simpler yet: Does $x_0 \gt 0$ imply that $x(t)\gt0$ for all $t$?

NOTE: This problem is known as a special case of Euler's three-body problem. It is discussed in great detail in "Integrable Systems in Celestial Mechanics" by Diarmuid Ó Mathúna, where the equations of motion are given in closed form using Jacobi elliptic functions, by transforming to what Mathúna calls "Louiville coordinates". I am currently working through the derivation of this, but as it is very technical, it will take me some time. It is still possible, that the question may be answered without the explicit equations of motion.

Background:

I'm currently working on a (2 dimensional) simulation of gravity which visualizes gravitational basins of attraction.

The simulation works as follows:

$n$ massive bodies are given an intial position. They are treated as static and will never change position during the simulation. Each body is also given a unique color property (for visualization purposes later).

Next, the simulation space is filled with particles. Their initial velocity is set to zero. Their trajectories are calculated via numerical integration.

When a collision between a particle and one of the massive bodies is detected, the initial position of the particle is assumed to lie in the basin of attraction of that body (with which it collided). A collision occurs when the distance to a body is below a certain threshold. The initial position of the particle is then marked in the color of the planet it collided with.

In general the resulting pictures are very complex.

Here are some more examples: 1, 2, 3, 4*

As you can see the basins are generally fractals.

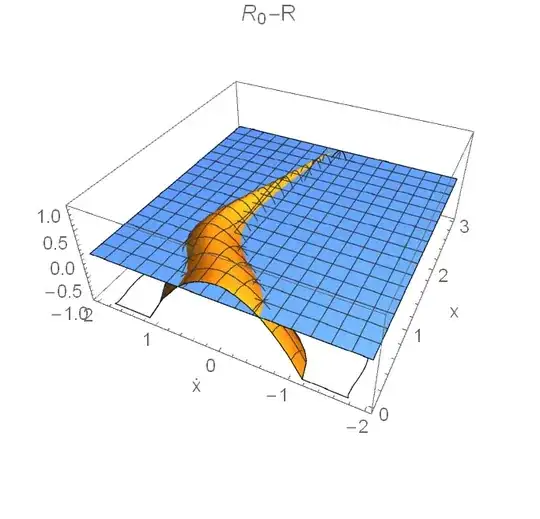

Yet, when I simulate the above described setup, where $n=2$ and the masses of the two bodies are the same, the following picture is produced.

Where blue pixels represent initial positions in the basin of attraction of the mass at point $A$, red pixels those in the basin of the mass at point $B$ and black pixels in neither. (A thin strip of black pixels lie on the line $x=0$, where they oscillate around the origin)

The picture is clearly devided into two half planes, yet I can not explain why. Any help explaining this fact would be much appreciated.

I tried solving the problem analytically using Lagrange's equations of the second kind. I set: $$T=\frac{m}{2}(\dot{x}^2+\dot{y}^2)$$ $$V=-GM m\left[\frac{1}{\sqrt{(x-d)^2+y^2}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{(x+d)^2+y^2}}\right]$$ And obtained the following equations of motion: $$\ddot{x} = -GM\left[\frac{x-d}{\left((x-d)^2+y^2\right)^{\frac{3}{2}}} + \frac{x+d}{\left((x+d)^2+y^2\right)^{\frac{3}{2}}}\right]$$ $$\ddot{y} = -GM\left[\frac{y}{\left((x-d)^2+y^2\right)^{\frac{3}{2}}} + \frac{y}{\left((x+d)^2+y^2\right)^{\frac{3}{2}}}\right]$$

Where $x$ and $y$ are the coordinates of the particle, $m$ the mass of the particle, $M$ the mass of the massive bodies and $d$ the distance (in the $x$-direction) from the origin of the massive bodies.

I converted this into a system of four first-order differential equations and tried solving it using Maple's dsolve, but it's been stuck Evaluating for two hours now, so I don't think it's going to finish...

Another thing I tried is showing that a particle on one side will never have enough potential Energy to ever cross the line $x=0$, but then I considered the starting location $\vec{r}_0=(2d,y_0)$ with arbitrary $y_0$. $$V((2d,y_0))=-GMm\left[\frac{1}{\sqrt{d^2 + y_0^2}} + \frac{1}{\sqrt{9d^2 + y_0^2}}\right]$$ Then I could easily show that there exists a point on the line $x=0$ that has less potential, therefore I imagined the particle could reach that point and still have "kinetic energy leftover" to cross the line. One such point would be $\vec{r}_1=(0,y_0)$, since: $$V((0,y_0))=-GMm\left[\frac{1}{\sqrt{d^2 + y_0^2}} + \frac{1}{\sqrt{d^2 + y_0^2}}\right]$$ From which it became evident that $$V((2d,y_0))\gt V((0,y_0))$$ A flaw in this argument could be, that the particle could never reach $\vec{r}_1$ (or any point on $x=0$ which has less potential). Another fact I can not prove.

[1]I wrote a small paper on the case of the equalateral triangle, where the case of the two bodies was glossed over. Since I am not working on a video series about the subject, I revisited this case and couldn't prove the fact of the two half planes.

– NiveaNutella Dec 13 '19 at 16:34Not sure, if it's ok to add this here. It is not supposed to be a discussion, merely the essence of what I researched after reading both of your comments.

– NiveaNutella Dec 13 '19 at 22:09