In most basic statistical physics/condensed matter discussion the density of states is used to convert a discrete sum to a continuous integral

$$\sum_{\alpha} \mapsto \int d\epsilon \ g(\epsilon).$$

For example, a common derivation of the density of states can be done by considering the volume of a sphere in $k$-space (corresponding to the total number of states with wavevectors $<k$) and then taking the derivative e.g. Wikipedia - k-space topologies.

However under what conditions is this accurate?

Indeed, the continuous density of states method breaks down for Bose-Einstein condensates because the density of states

$$ g(\epsilon) = \frac{\sigma}{4 \pi^2} \left( \frac{2m}{\hbar^2} \right)^{3/2} \sqrt{\epsilon} $$

gives no weight to the states at $\epsilon = 0 $ since $g(\epsilon) \propto \sqrt{\epsilon}$.

For example, jacob1729's answer here describes that

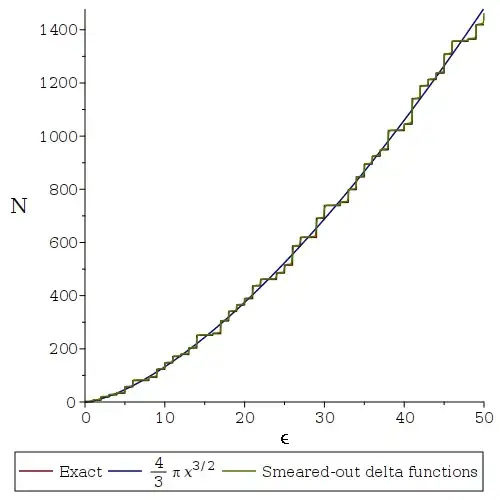

One option for this is of course $g(\epsilon)=\sum_{\alpha}\delta(\epsilon-\epsilon_\alpha)$ but in practice this might be smeared out a little whilst not hurting the approximation (eg convolve with a Gaussian of width $\Delta\ll kT$).

This is an approximation. We expect this approximation to become exact as the level spacing goes to zero under the assumption that the states do not become macroscopically occupied.

My questions

- How can we justify/quantify the statement "under the assumption that the states do not become macroscopically occupied" and what are the mathematical conditions for the convergence of the integral?

- In the derivation using $k$-space topologies, where is the assumption that the density of states cannot be small made? In the case of the Bose-Einstein condensates, if this density of states is wrong at $\epsilon = 0$ why does it work at all for larger energies?

The question How to prove that sum converges to integral using density of states? appears relevant but I still don't understand why the density of states fails for low energy states (for example, as in Bose-Einstein condensates).