Think of a motion profile as a graph of speed vs. time.

If you drive your car down the road:

- Your initial speed is zero.

- You start pressing the accelerator pedal.

- The car starts moving slowly.

- You keep pressing down on the accelerator.

- The car accelerates faster.

- As you approach your targer speed you let go of the accelerator.

- The car settles on your target speed.

- You approach a stop sign and start pressing on the brake pedal.

- Your speed goes down and as you approach the stop sign you start letting go of the brake pedal.

- You come to a smooth stop.

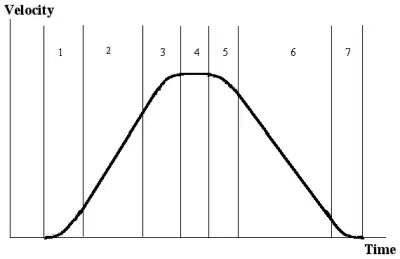

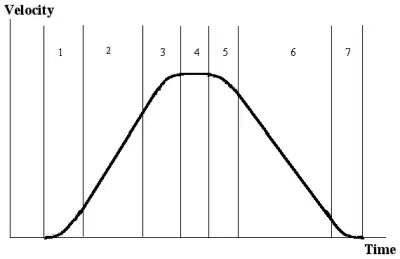

I just described roughly what people would refer to as an S-curve motion profile or a limited jerk profile. To experience jerk in your car try this next time you stop, press the brake pedal but do not let it go at all until the car comes to an absolute stop. This also illustrates the importance of controlling the motion profile for smooth motion. When graphed this looks something like this:

You can see the S in there. A trapezoidal profile has straight lines and three sections and as per our car experiment above will force you to reduce your acceleration to avoid "jerking" at the "corners" (discontinuities).

You should also think about this in terms of the equivalent position vs. time graph. A motion profile executed in a robot, e.g. is typically moving from one position to the other.

Motion profiles are critical for achieving smooth and reliable high performance motion. With more than one motion axis they are also important for synchronizing the motion. Without them your motion might look like your car firing off a rocket to get started and locking the wheels to stop at the end of the street, not very pretty.

Additional reading:

https://www.pmdcorp.com/resources/get/mathematics-of-motion-control-profiles-article

speed = speed + accelaccel = accel + x. Also how do you change your acceleration and speed in your current code? What happens when you make a move shorter than 200 ticks? – Guy Sirton Mar 16 '14 at 23:56