(I have tested this approach before, and I remember it worked correctly, but I haven't tested it specifically for this question.)

As far as I can tell, both $\|\mathbf{v}_1\times \mathbf{v}_2\|$ and $\mathbf{v}_1\cdot \mathbf{v}_2$ can suffer from catastrophic cancellation if they are almost parallel/perpendicular—atan2 can't give you good accuracy if either input is off.

Start by reformulating the problem as finding the angle of a triangle with side lengths $a=|\mathbf{v}_1|$, $b=|\mathbf{v}_2|$ and $c=|\mathbf{v}_1-\mathbf{v}_2|$ (these are all accurately computed in floating point arithmetic). There is a well-known variant of Heron's formula due to Kahan (Miscalculating Area and Angles of a Needle-like Triangle), which allows you to compute the area and angle (between $a$ and $b$) of a triangle specified by its side lengths, and do so numerically stably. Because the reduction to this subproblem is accurate as well, this approach should work for arbitrary inputs.

Quoting from that paper (see p.3), assuming $a\geq b$,

$$ \mu = \begin{cases}

c-(a-b),&\text{if }b\geq c\geq 0,\\

b-(a-c),&\text{if }c>b\geq 0,\\

\text{invalid triangle},&\text{otherwise}

\end{cases}$$

$$

\mathrm{angle} = 2\arctan\left(

\sqrt{\frac{((a-b)+c)\mu}{(a+(b+c))((a-c)+b)}}

\right)$$

All the parentheses here are placed carefully, and they matter; if you find yourself taking the square root of a negative number, the input side lengths are not the side lengths of a triangle.

There is an explanation of how this works, including examples of values for which other formulas fail, in Kahan's paper. Your first formula for $\alpha$ is $C''$ on page 4.

The main reason I suggest Kahan's Heron's formula is because it makes a very nice primitive—lots of potentially tricky planar geometry questions can be reduced to finding the area/angle of an arbitrary triangle, so if you can reduce your problem to that, there is a nice stable formula for it, and there's no need to come up with something on your own.

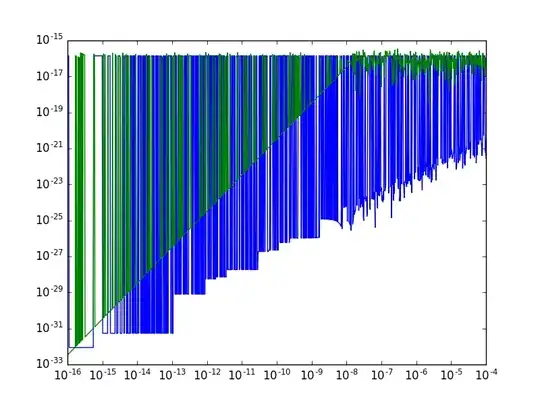

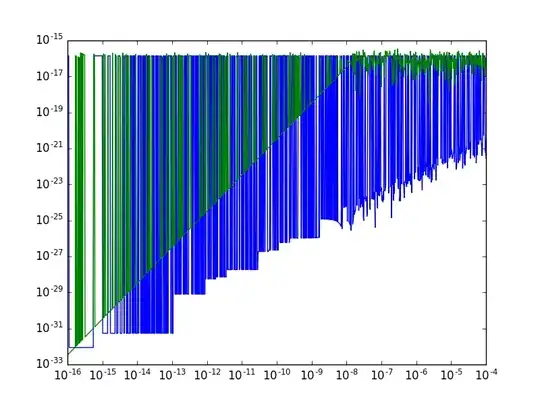

Edit Following Stefano's comment, I made a plot of relative error for $v_1=(1,0)$, $v_2=(\cos\theta, \sin\theta)$ (code). The two lines are the relative errors for $\theta=\epsilon$ and $\theta=\pi/2-\epsilon$, $\epsilon$ going along the horizontal axis. It seems that it works.