When a deadlock occurs, processing stops. This is a denial-of-service, which, like any other DoS, may serve as an intermediate step for a larger attack. For instance, if an Intrusion Detection System stops working (e.g. it enters a deadlock), then intrusions will be able to proceed undetected. Hollywood, in its infinite wisdom, has come up with very graphic expositions of such scenarios (that one is a classic).

Deadlocks are a classical issue in concurrent programming. They are so classical that some systems include "resurrection" safety mechanisms which try to reanimate a process past a deadlock. For instance, when a thread tries to acquire a lock which closes the deadlock circle, the locking system may detect it and not acquire the lock, instead reporting an error. If the caller does not properly check the error condition, it may proceed without the lock, modifying the data without synchronization with other callers. Data corruption and other undesirable consequences may then happen.

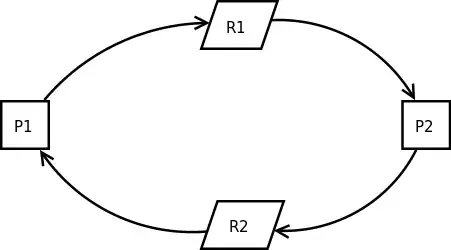

Avoiding deadlocks is a matter of correctness: a deadlock occurs because of a flaw in the overall application design (deadlocks are considered to be a "hard" type of bug because they cannot be pinpointed to a single location where a programmer forgot to put a test or miscomputed a constant; deadlock bugs appear at the architecture level). The relation to security is the generic one: it is not sufficient to ensure that bugs are not triggered under normal conditions, because attackers can often enforce abnormal conditions. For instance, even though the name of a normal user fits in less than 100 characters, you should still check that the name as entered by the user is not too big before trying to copy it into a 100-character buffer. Similarly, even if a deadlock cannot occur in a given application when external events happen at a "normal pace", an attacker can trigger unusual timings, e.g. launching 15 "password change" operations simultaneously on the same account.