You actually ask two separate questions.

What is the cause ... of this behavior?

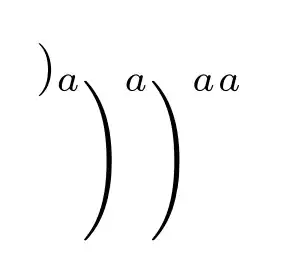

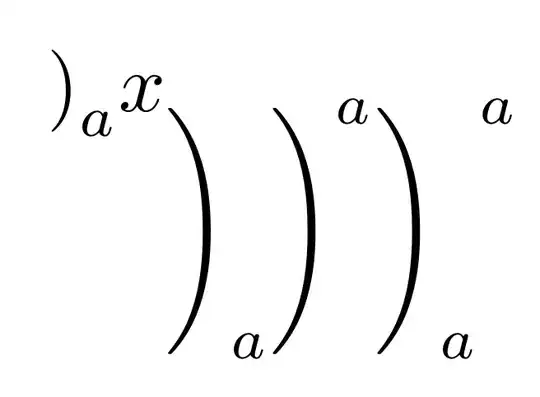

Consider the following, slightly more elaborate examples that involve mathematical delimiters, such as ) and ], and adjacent subscript and superscript terms.

\documentclass{article}

\begin{document}

$()_I$ ${()}_I$ $\left(\right)_I$ ${\left(\right)}_I$

$()^2$ ${()}^2$ $\left(\right)^2$ ${\left(\right)}^2$

$[]_u^v$ ${[]}_u^v$

\end{document}

The two main things to note in this screenshot are:

In a given row, the round parentheses and square brackets all have the same heights and depths. Same for the subscript and superscript terms in a given row.

In a given row, the subscript and superscript terms are placed more compactly, i.e., with smaller vertical offsets, in the first case than in the subsequent case[s].

So, in a given row, what distinguishes the first case from the subsequent cases? Take, say, the second row.

In the first case, the "math atom" that immediately precedes the ^ token (TeX's superscript material initiator) is ), which has TeX status "math-close".

In the second through fourth cases, the "math atoms" -- or should that be "math molecules"? -- that precede the ^ tokens are {()}^2, \left(\right)^2, and {\left(\right)}^2, respectively. What do these math atoms have in common? It's that their TeX status is "math-ordinary". Aside: encasing any math atom in curly braces changes its status to math-ordinary. And, the entire \left(\right) math atom also has status math-ordinary.

Now, TeX's superscript and subscript placement rules differ importantly in terms of the vertical offsets that get applied, depending on whether the material that immediately precedes the ^ and _ tokens has status math-open/math-close or not. In particular, what you've (re)discovered is that the placement is tighter if the preceding math atom has status math-close than if its status is math-ordinary.

What is the ... rationale [for] this behavior?

My impression is that there are two separate reasons for TeX applying smaller offsets if the math atom that immediately precedes the _ and ^ tokens has status math-open/close.

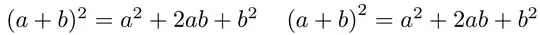

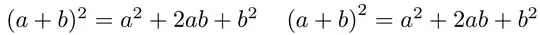

Compare the outputs of $(a+b)^2 = a^2+2ab+b^2$ and $\left(a+b\right)^2 = a^2+2ab+b^2$.

In the former case, all three instances of 2 are placed at the same height, which I would argue looks natural and harmonious. In the latter case, the first instance of 2 is placed noticeably higher than the other two; to me, that seems artificial, unnecessary, and visually distracting. (Aside: Having worked with TeX and LaTeX for more than 30 years, my opinion in this matter may well be a tad biased...)

In an inline-math context, applying smaller vertical offsets to any subscript and superscript terms that may be present significantly raises the odds that that the entire paragraph can be typeset with even spacing between lines. In fine typesetting, having even line spacing in a paragraph is considered to be very desirable.

Finally, you asked,

Since I might accidentally mix both syntaxes in my document, what is the best practice to ensure a uniform alignment of indices?

It's quite simple, really: Don't use the \left and \right auto-sizing directives unless doing so serves a discernible valid purpose. Applying this stricture to some of the preceding material suggests that there is no valid reason for using \left and \right in $\left(a+b\right)^2=a^2+2ab+b^2$...

\left(,\right)only if it makes a difference to(...), e.g. if you use\fracinside. – dexteritas Aug 31 '23 at 13:24_looks for the previous item, positions the index accordingly. In the second case, there is\right )which measured the size of the parenthesised things and changed its own size to fit. This influences the position of index. In the first case, there is just char)to set the position of index. Why the result is different in such a simple case, I do not know. – minorChaos Aug 31 '23 at 14:41)_seems to behave very reasonably and in fact, nice. This (probably) intentional behaviour is lost when\left..\rightis used, because the material is sort of boxed and the dimensions of protruding)will cause to change the positions of indexes. – minorChaos Aug 31 '23 at 21:32