Quick summary: \text can be used to ensure proper scaling with respect to the correct math style. When exactly should one use it for that purpose? What need is there for nested invocations of \text for that purpose?

amsmath's \text includes \mathchoice, which people may have encountered in the form of \mathpalette.

When one might want to use \text is explained here. An advanced use case for \text is to make sure that text within some sort of text box embedded within math mode scales correctly. A concrete example is my definition of a 180°-rotated iota (℩), which one can use to denote a uniqueness selector (here \trnupiota):

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{upgreek} % for \upiota

\usepackage{rotating} % for \rotatebox

\usepackage{amsmath} % for \text

\usepackage{accsupp} % for the right Unicode codepoint

\newcommand*{\trnupiota}{\mathord{%

\BeginAccSupp{method=hex,unicode,ActualText=2129}%

\text{\raisebox{\depth}{\rotatebox{180}{\(\upiota\)}}}% % with \text

\EndAccSupp{}}}

\newcommand*{\trnupiotaNoText}{\mathord{%

\BeginAccSupp{method=hex,unicode,ActualText=2129}%

\raisebox{\depth}{\rotatebox{180}{\(\upiota\)}}}% % without \text

\EndAccSupp{}}

\begin{document}

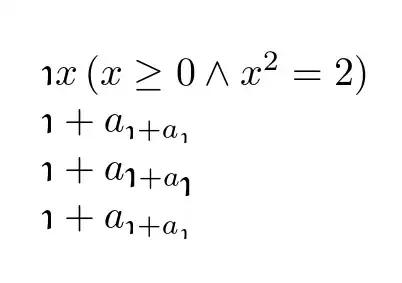

\(\trnupiota x \,(x \ge 0 \wedge x^{2} = 2)\)

% denotes the square root of 2, which is by convention non-negative

\(\trnupiota + a_{\trnupiota + a_{\trnupiota}}\)

% scales correctly

\(\trnupiotaNoText + a_{\trnupiotaNoText + a_{\trnupiotaNoText}}\)

% doesn't scale correctly

\end{document}

(One may also use an ordinary iota: ι; conventions differ.) The entire first line denotes "the unique x which is non-negative and equals 2 if squared":

As one can see, the \trnupiota scales correctly in the different math styles, while the \text-less \trnupiotaNoText doesn't.

As explained in the comment thread to the answer linked above, \text can be slow, especially when it is nested: the relevant material is typeset 4 times (so the time for that material is quadrupled). The 4-fold increase in compilation time normally affects only tiny formula chunks, but it would be good to know a few rules about when we can safely not use \text.

We also know (this is explained in the same comment thread) that, when amstext or amsmath is loaded, the following text macros already include the mechanics of \text: \textrm, \textsf, \texttt, \textnormal, \textbf, \textmd, \textit, \textsl, \textsc, \textup, \emph. That is, for those we don't need an additional \text around their invocations.

Let's figure out when we truly need \text within math mode. In my example, \rotatebox necessitates \text. The frequent box \raisebox necessitates \text. The text macros in the previous paragraph already include \text; an additional \text would be a waste of computing resources. But what about constructs like the following?

\raise0.5ex\hbox{MATERIAL}- I have a macro defined as

\mathbin{\text{\ooalign{...\raise0.1ex\hbox{\(...\raisebox{...}{\scalebox{...}{\(MATERIAL\)}}...\)}...}}}. (Don't ask why; it's about my use of\ooalignand also consistency in between definitions.) The first use of\(...\)in my macro effectively creates a\textstyle(independent of what the outermost math style in which the macro is called is in; is that right?), and therefore the following\raiseboxcauses no problems and doesn't necessitate another\text?

How can one characterize the contexts in which such use of \text within math mode is needed? I'm looking for an answer along the lines of "all boxes which are based on the TeX primitives X, Y, Z, if they are within non-\textstyle math mode"? What else is there to know?

\(...\)always produce a\textstyle? Surely some insightful things can be said. This is also meant to be useful to a true beginner. – Lover of Structure Apr 20 '14 at 05:15